Lab-grown fish – the next step in the fight to save our ocean?

Three billion people worldwide depend on fish as their primary source of protein, and demand is rising – but climate change and overfishing are depleting fish stocks the world over. Could lab-grown seafood be part of the solution?

W e all know the damage that our global addiction to eating meat is wreaking on the environment. One possible remedy that has been making big waves over the past few years is lab-grown meat: beef, for example, grown in a laboratory from a cluster of animal cells. Now a new group of biotechnology startups are taking the same approach to seafood. The global demand for fish is on the rise as our oceans’ capacity to satisfy it is running dangerously low – which is why biotech entrepreneurs around the world are working to bring lab-grown seafood to our plates in the near future.

Net profits

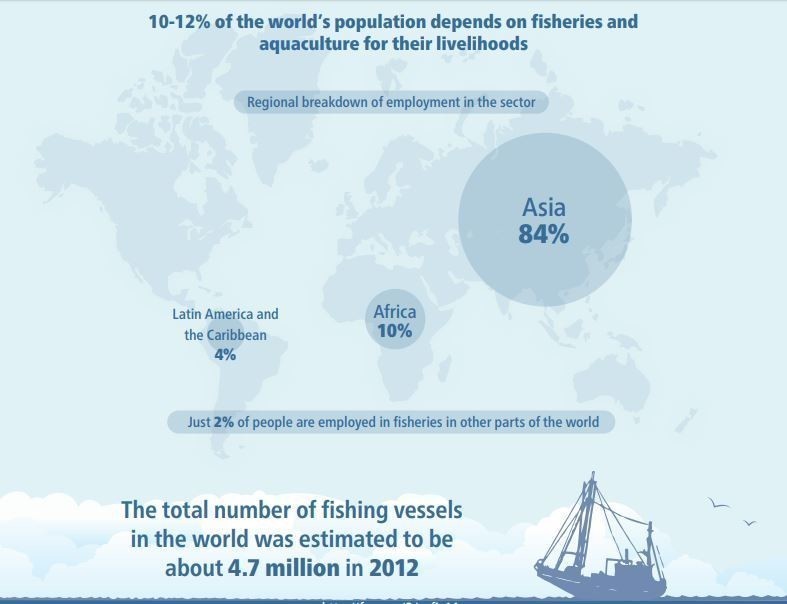

Seafood, both farmed and wild-caught, is the main source of protein for three billion people around the world. The oceans are their larder – but the shelves are beginning to empty. Years of overfishing have pushed many of our marine ecosystems to their limits; today, 85% of global fisheries are either at the limit of what they can sustainably produce or are overfished. Climate change, too, is already having an effect on fish stocks around the world. The acidification and rising temperature of the oceans is making it harder for creatures like shrimp and oysters to make their shells. Creatures further down the food chain, such as zooplankton, are being similarly affected.

Farmed fish, meanwhile, presents its own set of challenges, including increased pollution and disease – and the rising sea temperatures and increasing extreme weather events that climate change will bring are going to make life harder for fish farmers, too.

Fin-tech

Lab-grown seafood promises an ethical, non-polluting and entirely sustainable solution to these problems – and it’s getting closer. In June this year, a US-based start-up called Wild Type reached a milestone with the first large-scale test of its lab-grown salmon. The fish was served to diners in Portland, Oregon, as part of a tasting menu that included ceviche, salmon tartare and sushi rolls. It was the first time the company had produced more than a pound of its product.

Others are getting in on the action, too. California-based Finless Foods is developing lab-grown bluefin tuna, while Shiok Meats – a start-up from Singapore – is growing shrimp meat in its research labs, and has plans to move into cultured crab and lobster, too. Nevertheless, the technology is still in its infancy, and there are many hurdles to overcome before these products find their way onto our supermarket shelves. Some of these challenges are technological; Wild Type’s salmon, for example, has to be served raw, as heating it causes the meat to fall apart (although the company says it is developing a new variety of salmon meat that can be cooked).

The taste isn’t quite there yet either, according to a reporter from Bloomberg who sampled Wild Type’s menu: “While the texture closely approximated wild fish, the taste, however, was lacking. It wasn’t unpleasant, nor unfamiliar. Just faint.”

And production costs are still extremely high. Shiok Meat’s lab-grown shrimp, for example, costs a reported $2,270 per pound, while each of the salmon sushi rolls made with Wild Type’s salmon contained around $200-worth of meat.

Scaling up

But if the progress made by the lab-grown meat sector is anything to go by, those costs could start to fall pretty quickly. After all, it cost a reported $330,000 to get the world’s first lab-grown burger, which was cooked and served to food critics in London back in 2013, onto the plate; two years later, according to the scientist behind the project, the cost of a cultured burger had fallen to $11.

As the taste of lab-grown fish and the technology used to produce it improve, and as costs begin to fall, cultured seafood could begin to be produced at scale (no pun intended) within the next couple of decades. Soon, the salmon in your sushi could be helping to alleviate the unsustainable pressure we are exerting on our fast-depleting oceans.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.