Funding first for Philippines to get typhoon early warning

The Philippines has secured funding from the U.N.’s Green Climate Fund, its first under a scheme to provide financial assistance for adaptation and mitigation in countries vulnerable to climate change.

- The Philippines has secured $10 million in funding from the U.N.’s Green Climate Fund, its first under a scheme to provide financial assistance for adaptation and mitigation in countries vulnerable to climate change impacts.

- The funding will go toward establishing a multi-hazard and impact-based forecasting and early warning system in four pilot areas in the country to assist local government units in implementing appropriate early responses to hazard alerts.

- The Philippines is one of the countries most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, which include increasingly more intense storms slamming into the country from the warming Pacific.

W

hen Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippine province of Leyte on Nov. 3, 2013, Sabrina Lasquiet and her husband, Danilo, didn’t leave their home, even though their village in Tacloban City lay in the direct path of the storm. They received the alert but shrugged at the notion of the coming “storm surge,” an expression they didn’t know. “We disregarded the news report because we assumed it’s just one of the usual storms. But we were wrong — we never expected [Haiyan] to be that strong.”

More than 6,300 people died during the onslaught, and houses and infrastructure were demolished, including the couple’s bungalow, which was razed to the ground. With an average of 20 typhoons hitting the Philippines every year, storm alerts are common in provinces like Leyte, which, located on the eastern side of the archipelago, are exposed to the storms that brew in the Pacific in the latter half of the year. The intensity of these storms is expected to increase as a result of climate change, posing an even greater threat to communities already ill-prepared to deal with the impacts of existing storms.

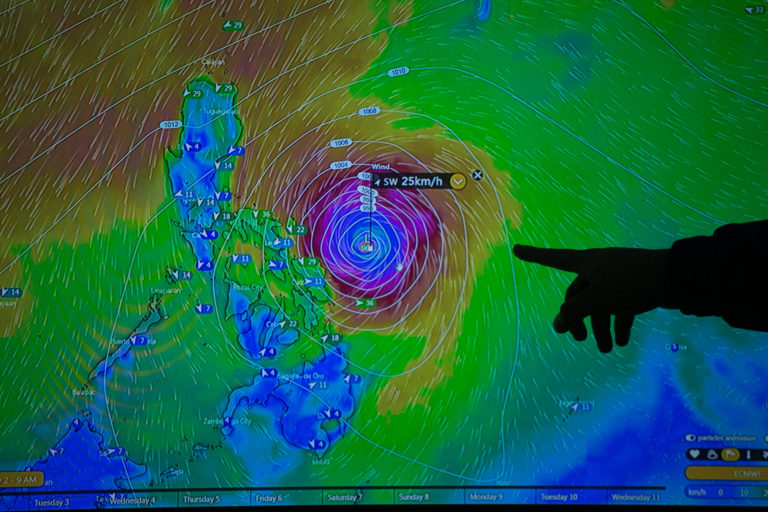

The track of Typhoon Kammuri on a TV screen. Image courtesy Basilio Sepe/Greenpeace Philippines

First time

It’s to address this lack of a sense of public urgency about storm warnings and impacts that the Philippines received its first funding from the U.N.’s Green Climate Fund (GCF). Approved on Nov. 13, the funding will go toward an intensive impact-based forecasting and warning system to make locals like Sabrina understand hazards, and to help local governments decide on appropriate early warning responses.

“Good forecasts don’t always translate to good response,” Thelma Sison of the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Administration (PAG-ASA), the country’s meteorological agency, said at a press conference in Manila on Nov. 19. She identified two factors that influence the poor response: the difficulties residents face in addressing and understanding hazard alerts, and the general lack of awareness about what actions to take after receiving an alert.

The Multi-Hazard Impact-based Forecast and Warning Systems (MH-IBF-EWS) program secured a $10 million grant from the GCF board. It’s the first initiative in the country to get funding from the GCF, a financial mechanism under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to assist developing countries in implementing climate adaptation and mitigation measures.

The investment will make them safer. Photo by Avel Chuklanov/Unsplash

Four sites targeted

The total cost of the project is $20 million, with the Philippine government committing to cover half through the met agency’s modernization program. Four sites are being eyed for the program: Tuguegarao City, the provincial capital of the province of Tuguegarao; Legazpi City in the Albay region; Palo in the province of Leyte; and New Bataan in Davao de Oro, a province formerly known as Compostela Valley.

“This program will improve and enhance our early warning systems which will be useful on a community level,” said Manny de Guzman, commissioner for the Philippine Climate Change Commission. “This is [to] enhance and make our early warning systems more accurate. Local government units will develop protocols on what to do when they receive these types of warnings and alerts from PAG-ASA.”

The five-year project will include a series of community consultations for a “localized” and “people-based” approach. “The likelihood of the impact will be developed with stakeholders,” Sison told Mongabay. “Every locality has a different approach to this and we will help them draft the matrix on how this will impact them … this will be very site-specific and there will be a corresponding response table.”

The project is expected to change the country’s forecasting paradigm, Sison said, moving away from the mindset of “what the weather will be” toward “what the weather will do.” The “impact estimation” aspect will identify the affected areas, infrastructure and possible damage to services. “By giving the potential impacts of a hazard, disaster management agencies, local governments, and the general public will have a better understanding of the risks and will more likely conduct early actions and early response,” Sison said.

The project will be the first of many, de Guzman said. “We are developing more project proposals for GCF funding,” he told reporters in Manila on Nov. 19. “We’re thankful that this proposal was approved and we look forward to accessing more funding from GCF in the future to build our country’s resilience to climate change-related impacts.”

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.