We need more early warning systems to adapt to extreme weather. Here are three examples from around the world

As climate change makes heatwaves and other extreme weather events more common, there is growing appreciation that early warning systems are a wise investment.

I

t is often hot in Ahmedabad in May. But in 2010 the seven million inhabitants of this city in Western India saw the temperature reach a dangerously high 48.6°C. The heatwave killed an estimated 1,344 people.

Five years later, the temperature hit the high 40s again, resulting in hundreds of deaths across many other parts of India. But in Ahmedabad, this time just seven people died. Why the difference?

The city was better prepared. An early warning system put in place after the 2010 experience meant the authorities knew a heatwave was coming, and residents knew what to do about it.

Ahmedabad’s early warning system and action plan is now being seen as a model for other cities. More generally, as climate change makes heatwaves and other extreme weather events more common, there is growing appreciation that early warning systems are a wise investment.

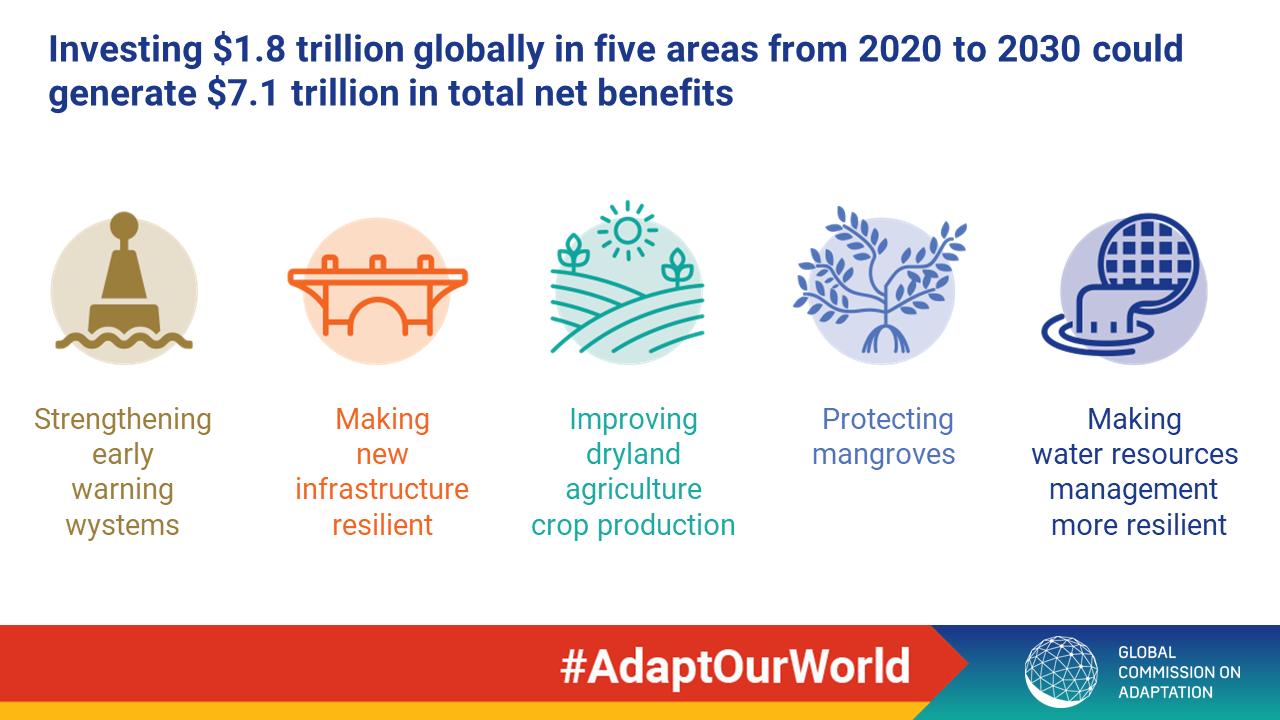

According to research for the Global Commission on Adaptation’s report Adapt Now: A Global Call for Leadership on Climate Resilience, early warning systems can pay for themselves many times over: in developing countries, economic losses of between US$3 and 16 billion per year could be averted by spending $800 million on early warning systems.

In 2010 in Ahmedabad, weather forecasts were available, but only two days in advance – and municipal agencies barely communicated with one another about the impending extreme heat.

By 2015, accurate longer-range weather forecasting was in place: the authorities had seven days notice that extreme heat was likely to be coming. And communication channels were established, with a designated official in charge of their use.

As the heatwave approached, health officials, emergency response teams, community groups and media outlets were put on alert. Hospitals were stocked with ice packs. Temples, malls and public buildings were designated as “cooling spaces”. Areas of the city with especially vulnerable populations had already been mapped.

Thanks to public information campaigns, Ahmedabad’s residents were better informed than in 2010 about basic precautions, such as drinking lots of water and not going outside in the afternoon. After additional training, Ahmedabad’s medical professionals were better able to diagnose and treat heat-related illnesses.

Getting the word out

Later in 2015, the Paris COP21 summit saw the launch of an initiative called CREWS – Climate Risk and Early Warning Systems – a collaboration of partners including the World Bank, World Meteorological Organization and United Nations.

CREWS projects include an investment of over $2 million in Burkina Faso, where four-fifths of the population depend on agriculture, including livestock and forestry. Lives and livelihoods are intensely vulnerable to heat waves and droughts, floods, storms and strong winds.

The project has been working to strengthen the country’s National Meteorological Service, and its cooperation with government departments and organizations that can effectively get the word out to local communities about impending extreme weather.

Even if there is limited scope to avert the damage, early warning can speed up the response and recovery – for example, lining up emergency food supplies, maximizing the supply of clean water and reducing the impacts on health.

Smooth coordination

Early warnings can be useful for many and varied types of events: Shanghai’s MHEWS (Multi-Hazard Early Warning System) covers 14 – cyclones, heavy rain, heavy snow, cold surges, strong wind, dust, heat waves, droughts, thunder and lightning, hail, frost, heavy fog, haze, and icy roads.

MHEWS has a broadly similar approach to the efforts in Ahmedabad and Burkina Faso – improving weather forecasts, raising public awareness and ensuring smooth coordination among the relevant municipal agencies.

Shanghai was one of the first examples of a MHEWS system. There is now an International Network for Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems, coordinated – like the Burkina Faso project – by the World Meteorological Organization.

It spreads awareness of good practices in early warning systems, such as assigning clear roles and responsibilities, conducting risk assessments, and ensuring that warnings are comprehensible and authoritative.

As climate change intensifies, early warnings will become ever more important. Even 24 hours warning of a coming storm or heatwave can lead to 30% less damage, according to the GCA. In Ahmedabad, the 2019 edition of the action plan claims it has saved 2,380 lives already.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.