2 for 1: the investments that build resilience against pandemics and extreme weather

Dedicated climate funds have historically underfunded activities in the health sector. The right investments now will strengthen our position against the effects of climate change as well as pandemics.

A s the coronavirus pandemic continues to wreak havoc, the world’s energies are rightly focused on efforts to contain the virus and manage the economic fallout. Yet, in the background, the climate emergency remains as urgent as ever

Indeed, climate-exacerbated shocks may well overlap with the COVID-19 crisis, disrupting efforts to contain the virus, stretching emergency services beyond the breaking point and delaying economic recovery.

For example, on April 8, a major cyclone battered Pacific islands including Fiji, knocking out power and damaging infrastructure in a country already consumed with COVID-19 containment efforts. In New Orleans, where emergency and health services are laboring under tremendous pressure to cope with the pandemic, residents have watched the Mississippi River rise by a foot within a week; more heavy rains threaten severe flooding, potentially compounding the emergency. Meanwhile, forecasters are projecting a “significantly above normal” Atlantic hurricane season, raising the prospect of communities having to fight both major storms and the virus.

Authorities in New Orleans are trying to tackle the pandemic. Meanwhile the Mississippi River has risen by a foot within a week. Photo by Louisiana National Guard

To manage the twin threats of the coronavirus pandemic and climate change, building resilience against both is imperative and urgent. We are going to have to multitask on this one, as delay will cost lives and livelihoods.

But how to do so, in the face of a recession, falling government revenues and huge pressure on public budgets to fund multiple priorities? Investments in COVID-19 response and in climate change resilience must work together and reinforce each other, rather than compete for resources. Here are three ideas on how to do it.

Healthcare investments can help pandemics and climate change

Climate change is already a public health threat, one that will grow with time. Rising average global temperatures are exposing more and more people to dangerously high temperatures every year. Wildfires degrade air quality to the detriment of human health, as they have in California and Australia.

Heavy rains and floods can carry pathogens and toxic chemicals that contaminate drinking water supplies. Major storms regularly inundate emergency rooms with people injured by violent winds. And warmer temperatures are expanding the geographic reach of vector-borne diseases such as zika, dengue and malaria.

Enter the coronavirus.

In the coming weeks and months, billions of dollars will flow into healthcare sectors around the world as part of the coronavirus response. Some of this spending will address immediate shortages of medical personnel, coronavirus testing, life-support equipment and protective gear.

But other investments will go into strengthening countries’ healthcare infrastructure, information technology and surge capacity. Many of these investments could simultaneously make communities more resilient to both pandemics and climate change.

Consider, for example, investments in disease surveillance, including the development of case databases that can be accessed instantly by all the relevant government agencies and civil society organizations in a country. These will help detect viral outbreaks as well as climate change-driven shifts in vector-borne diseases.

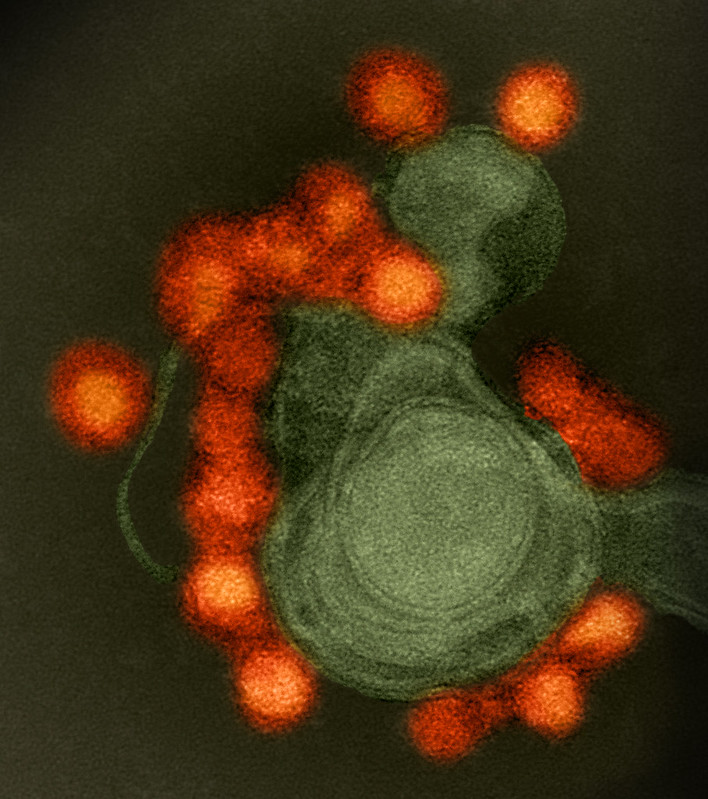

Warmer temperatures are expanding the geographic reach of vector-borne diseases such as zika. Photo by NIAID

Another example is the Rambam Health Care Campus in Israel, which has an underground parking lot that can be converted into a 2,000-bed, full service medical clinic in 72 hours. Such facilities can serve to respond quickly to a pandemic, as well as to provide treatment in case of a climate-related disaster.

At the same time, providers of climate finance should invest more in public health.

Our research suggests that dedicated climate funds, such as the Green Climate Fund, the Climate Investment Funds, and the Adaptation Fund, have historically underfunded activities in the health sector relative to what countries say they need to prepare for climate change. These organizations should identify investments that help countries to deal with both climate-related impacts and pandemics.

For example, the Caribbean island of St. Vincent and the Grenadines launched the Georgetown Smart Hospital Project. Its goal is to retrofit medical facilities to withstand hurricanes and continue to provide service during extreme weather. In case of a pandemic, medical treatment must be delivered, regardless of climate-related disasters. The Texas Medical Center in Houston made similar investments after Tropical Storm Allison in 2001.

Speedy finance is key for a successful response

In the aftermath of a disaster – whether it’s a pandemic or a climate-related catastrophe – rapid finance is key for a successful response. Governments have access to a variety of tools to help them finance disaster response. These tools include national disaster funds, contingent credit lines (fast-disbursing loans), parametric insurance products (insurance policies that trigger automatically when certain conditions are met) and catastrophe bonds (like insurance policies, but traded in markets).

Countries with the most effective disaster risk finance (DRF) strategies typically deploy combinations of these tools to protect against the various layers of risk a country faces, matching risks and tools based on what is most cost-effective.

Over the past decade and a half, a disaster risk finance architecture has emerged to serve mostly low- and middle-income countries, focusing primarily on earthquakes, hurricanes, floods and drought. The same or similar instruments could be used to manage pandemic risks.

This is beginning to happen.

Countries are tapping World Bank contingent credits – typically used to raise fast cash after hurricanes and floods – to access to over $1.2 billion in funds for COVID-19 response. Though currently few in number, products built expressly for pandemics deserve increased attention.

For instance, African Risk Capacity (ARC), a regional risk pool created originally to provide drought insurance to African governments, is developing a product to help governments respond to outbreaks of Ebola, Lassa fever, Marburg, meningitis and – as ARC recently announced – COVID-19.

Not all disaster risk financing products will be a good fit for pandemic response – the World Bank’s 2017 pandemic catastrophe bond has been widely criticized, for example – but those that can deliver money quickly before impacts become widespread could be valuable.

Disaster-responsive social safety nets could be as beneficial in a pandemic as they are in extreme drought. Photo by ICRAF

The problem is that the DRF architecture suffers from several shortcomings and needs to be strengthened urgently. As we point out in a recent paper, only a minority of countries with access to these DRF tools is actually deploying them in combination to cover their catastrophic risks. As a result, many countries remain underinsured and vulnerable.

Strengthening the system will require several things. Boosting the amount of cheap loans and grants available to help countries assess and measure their risks will be key, as will developing new DRF products and services. Making existing products more affordable is also necessary.

In our paper, we introduce three options for how this can be done quickly and effectively: expanding the role of the World Bank’s International Development Association, promoting the role of regional multilateral development banks, and creating a new and scaled-up DRF vehicle.

How can programmes actually protect society?

While access to rapid finance for post-disaster response is critical, it’s not enough. Governments need systems in place to deliver those resources to the communities that need them the most. Social protection programs that can quickly and automatically scale up after a disaster – be it a pandemic or a climate-related disaster – offer one promising approach.

Such programs provide rapid, additional cash to supplement income to enable households to cover immediate crisis-response costs. For example, Kenya’s Hunger Safety Net Programme (HSNP) normally provides cash transfers to households that can’t afford to buy enough food. During droughts, the HSNP automatically scales up to provide emergency cash to additional households.

Disaster-responsive social safety nets could be equally beneficial in a pandemic, when many households face unexpected loss of employment and income, as well as unexpected medical expenses. Emergency cash transfers could help people avoid dangerous choices between safeguarding their health and the health of others and earning enough to pay for basic necessities. While pioneered in developing countries, the principle can be applied in developed countries too.

We find ourselves in uncharted territory, but tools and knowledge that already exist for climate resilience should also be deployed to help communities cope with pandemics, and measures to protect us from this and future pandemics can also help build resilience to climate impacts. While responding to the current coronavirus crisis must be everyone’s primary concern, we should not lose sight of how actions and investments today could potentially prepare us for other crises, including the looming climate crisis.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.