Photo by Swansea for Europe/Flickr

How making the switch to plant-based milks can support farmers and ease water scarcity

E

ric Ziehm grew up on a dairy farm in Hoosick, New York. Although the operation has not changed much since his childhood — the family still milks a herd of Holsteins, and a tanker still pulls up each week to haul off the milk — the dairy industry has undergone a dramatic transformation in that time.

Milk prices dropped from nearly US$26 per hundredweight in 2014 to just over US$13 in May of this year — the lowest national monthly price in more than a decade. Plummeting prices mean that it costs dairy farmers more to produce a gallon of milk than they earn when they sell it.

Farmers are struggling to keep their milking parlors operating. The number of dairy farms in the U.S. has declined more than 50% since 2003, leaving just 34,187 licensed dairy herds nationwide in 2019, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Meanwhile, sales of plant milks have increased in recent years. And a 2019 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that embracing a plant-based diet could help address the climate crisis. Trading conventional dairy for plant milks could be part of the solution.

Such concerns about the future of the dairy industry and the environmental impact of conventional agriculture led Ziehm to take a different path in 2017: He started his own organic farm, High Meadows of Hoosick, milking 200 Holstein and Jersey cattle and growing 20 acres (8 hectares) of oats for Hälsa Foods, makers of plant-based milk products.

“There is a sector of the population looking for a clean, healthy product, and I want to fill that demand,” he says.

There is a sector of the population looking for a clean, healthy product, and I want to fill that demand.

Eric Ziehm, dairy farmer

Making the Switch

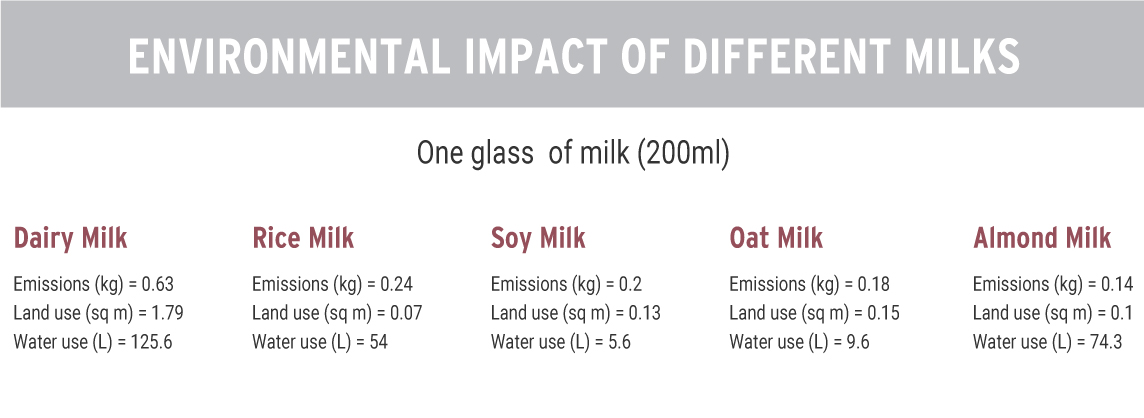

Research shows that one 200-milliliter (7-ounce) glass of dairy milk produces nearly three times more greenhouse gas emissions than a glass of rice milk, and at least three times more than soy, oat or almond milk, and requires 10 times as much land as oat milk. Even thirsty crops like almonds require almost half the amount of water as it takes to produce the equivalent amount of dairy milk.

Paragraph

Source: BBC News

Miyoko Schinner, founder and CEO of Miyoko’s Creamery, a company that produces vegan cheeses, butter and other products, spoke at the 2019 International Dairy Foods Association conference. She told dairy farmers and food producers that switching to plant agriculture provided a way for dairy farmers to stay true to the land and “become part of the solution for a sustainable future.”

Concerns about the environment and the future of the dairy industry has led to several partnerships between dairy farmers and companies making plant milk. Hälsa, Miyoko’s Creamery and the Swedish oat drink company Oatly all have announced programs to help dairy farmers transition to crops like oats and cashews that can be used to make plant milk, butter, cheese and yogurt.

Several dairy companies have added plant milks to their portfolios. Minnesota-based Live Real Farms launched blends that contain 50% dairy milk and 50% almond or oat milk, and HP Hood LLC, one of the largest and oldest dairy companies in the country, launched Planet Oat Oatmilk last year.

After 90 years in the dairy business, Elmhurst Dairy rebranded as Elmhurst 1925 and transitioned to producing cashew, almond, oat and hemp milks. Heba Mahmoud, vice president of marketing for Elmhurst 1925, attributes the pivot to declining demand for dairy milk and increased interest among consumers in plant-based diets.

Indeed, sales of plant milks in the U.S. increased 14% in 2017–2019.

“Consumers were going dairy-free for the purposes of improving their health and the health of the planet [and] taking notice of brands that were putting the environment first,” Mahmoud says.

Balancing the environmental impacts of plant-based milks

Plant milks are not without their own environmental impacts. Pesticides used in almond production have been blamed for widespread bee deaths. Growing rice requires significant water — though still less than raising dairy cattle — and produces the highest greenhouse gas emissions of all plant milks. Coconut production poses threats to biodiversity (though how much is an ongoing debate). Therefore, wind-pollinated hazelnuts, niche crops like hemp and flax, and sustainably grown oats are often hailed as the top environmentally friendly plant milk choices, though more research would help in this area.

Hälsa is one company that has chosen to focus on oats. Co-founder Helena Lumme was sourcing oats from Finland, but thought the carbon footprint to ship them to the U.S. was too high. In search of a solution, she looked to partner with an organic dairy farmer who was closer than Scandinavia and wanted to transition to plant milks. Hälsa could reduce the environmental impact of its products, she reasoned, while offering farmers a guaranteed market for the crop and entry into the fast-growing plant milk market.

Lumme says some farmers who were originally disappointed that consumers were purchasing less milk now see “a bigger picture … and have to decide, ‘Do I want to go with this trend and grow what people want?’” News of Hälsa’s farm conversion program triggered countless calls from farmers eager to participate; Lumme hopes Hälsa will be working with 100 dairy farmers across the U.S. to source oats within the next five years.

Photo by Monika Kubala on Unsplash

It’s not going to happen overnight

In 2016, farmer Adam Arnesson took to Twitter to encourage struggling dairy farmers in his native Sweden to embrace opportunities to produce plant milk. His suggestion: Oatly should help dairy farmers transition away from animal agriculture and into growing crops for plant milk.

The oat milk brand liked the idea and contracted with Arnesson to diversify his 80-hectare (200-acre) farm in Örebro, Sweden, to include almost 16 hectares (40 acres) of oats for its oat beverage. The original three-year contract proved successful for both parties, and Arnesson has renewed for additional seasons.

Arnesson is also taking part in a pilot project to encourage other Swedish farmers to follow suit. Ten farmers, including two dairy farmers, are participating in a one-year-old pilot project that includes a commitment from Oatly to purchase oats for its oat beverages.

“If you’re a farmer and want to be a farmer for a long while, [these transition programs] should be of interest,” he says. “It doesn’t have to happen overnight; it’s possible to try it out and find complements to dairy production and decrease it over time.”

At High Meadows of Hoosick, Ziehm agrees. While continuing to produce the key ingredient for oat milk, he has no plans to stop milking cows.

“It is not about cow milk versus oat milk; it doesn’t have to be a competition,” he says. “I love agriculture … and I think there’s always going to be dairy. But the plant-based [product] fills a nice niche [and] it’s a valid option for producers that have the best interest of the environment in mind.”

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.