How nature is helping Indonesia adapt to an eroding coastline

Rising sea levels and sinking land threaten the Indonesian island of Java, which has lost 78% of its natural barrier, mangroves. But the results of a new project working with the island’s natural landscape could help stabilize the coastline.

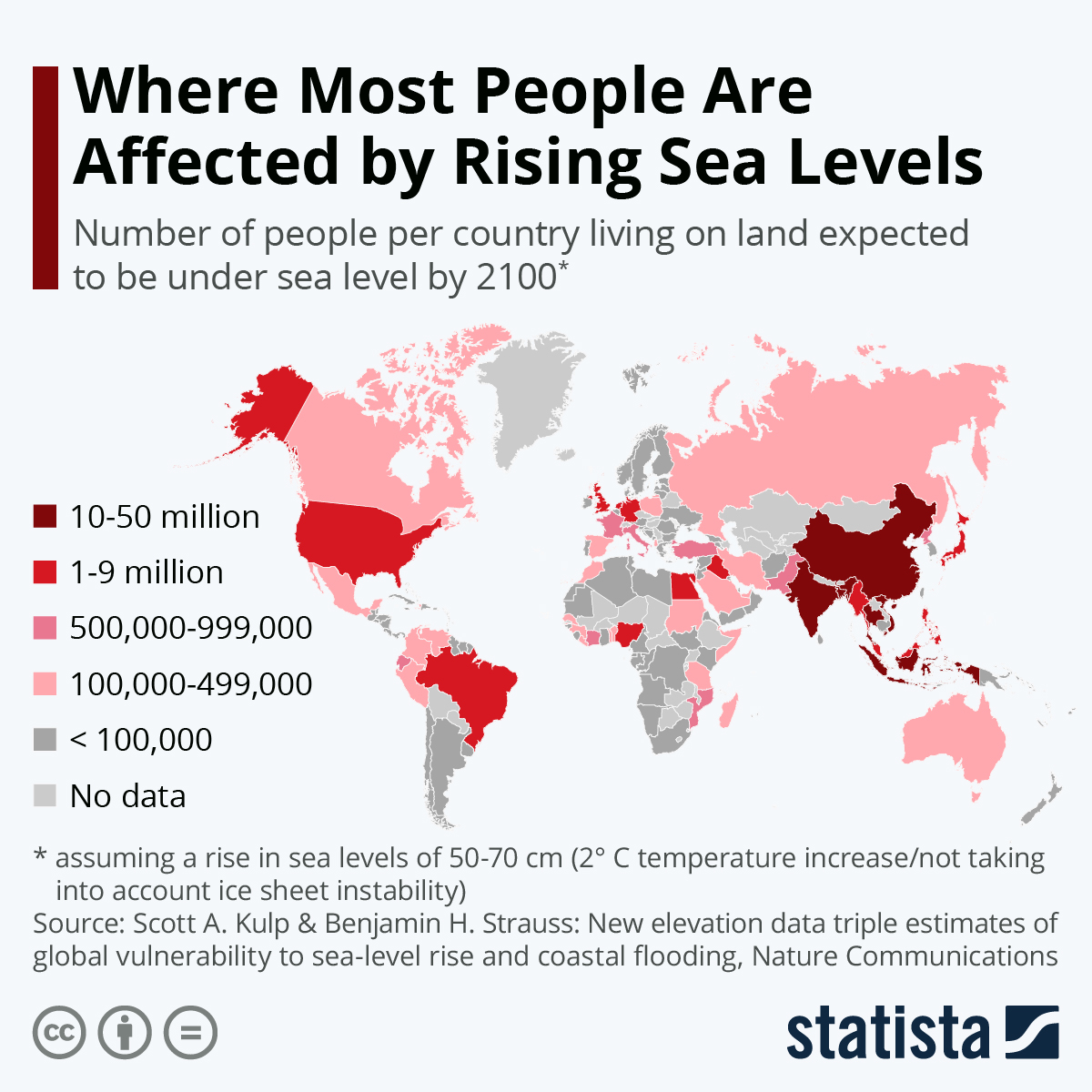

O nce the seat of an influential Sultanate, the district of Demak in Indonesia is under threat. The island of Java as a whole has lost 78% of the mangroves which once protected its low-lying coastline from storms and erosion, according to Wetlands International. In Demak, this loss is compounded by rising sea levels and sinking land – the result of groundwater abstraction in a nearby city. The impact is stark with a retreating coastline and two villages flooded and evacuated along 20k㎡ of land, says the not-for-profit. Long-term, more than 30 million people in Java will be at risk from flooding and coastal erosion.

Previous efforts to address the problem, from building breakwaters and seawalls to replanting mangroves, have failed. Some were too expensive; others were not able to adapt to the new and changing climate of the region.

But a recent initiative by Wetlands International, Ecoshape, the Indonesian Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (MMAF), and the Ministry of Public Works and Housing (PU), brings fresh hope. Using a “building with nature” approach, a pilot project started in a small village is now rebuilding 20km of mangrove coast and involving local communities, government agencies and educational institutes along the way.

Unlike previous attempts, this work incorporates natural processes into water engineering practice. The first step in reviving the mangrove greenbelt, for example, was to restore sediment balance. Small-scale engineering techniques involving the use of permeable structures built along the at-risk coastline allow suspended sediments in the water column to be trapped. Once sufficient sediment is retained, it can be used to expand the intertidal area – the space where the sea meets the land between high and low tides – and ultimately a new coastline.

Local communities now own these permeable structures, which have been built in phases and now stretch 9km. Their involvement and knowledge of construction, monitoring and maintenance of the installations is crucial to the sustainability of the project. In areas where land subsidence makes mangrove restoration unfeasible, the permeable structures still halt the erosion threatening villages along the Northern Java coast.

For shrimp farmers and fishermen in Demak reliant on aquaculture, the Building with Nature project has also been vital. In the last decade, their income has significantly decreased owing to disease and pollution. This has led to further destruction of mangroves and exacerbated coastal erosion as communities built new ponds for farming.

The project has helped build the capacity and skills of traditional farmers through “Coastal Field Schools” teaching new aquaculture practices. This includes the introduction of a mixed mangrove-aquaculture (MMA) system, where parts of farming ponds are used to make space for mangroves, and training in pond and water management. Shrimp yields have tripled and margins doubled as a result, says Wetlands International.

Engaging local community members has been crucial to this project, from their involvement in conservation and restoration to a new financial model, the Biorights approach, allowing them to invest in sustainable practices. Devised by Wetlands International, this financial scheme involved 260 local people in Demak and involved grants for successful conservation projects, working with villages to incorporate mangrove rehabilitation into local economic plans and establishing a forum between community groups and government.

Even with the measures introduced by Wetlands International and the adaptation of local communities, if unsustainable groundwater extraction in the south west of Demak continues the entire 20km of the project could be undermined. This is the next challenge for Indonesia: to address groundwater extraction and find ways to adapt to subsidence and the risk of flooding in Demak and the city of Semarang.

To make this happen, short-term development must be balanced with the need for long-term sustainability at all levels of government, says Wetlands International. Policies that support its Building with Nature approach must become practice and ministries and agencies must continue to collaborate closely, especially when bringing together coastal zone management, climate adaptation and disaster risk reduction.

“Many coastlines around the world are eroding, putting millions of lives and livelihoods at risk. The solutions are already present in the natural world around us. We must shift our perspective and start building with nature instead of fighting against it,” says Femke Tonneijck, project manager of Building with Nature Indonesia. “This approach does not just work on coastlines, but also in rivers, cities and beaches and brings significant co-benefits for people. Nature must be part of the solution for every water infrastructure challenge!”

Up to 23.5km of permeable structures have now been built elsewhere in Indonesia by MMAF. For now, the success of the Demak project offers a bright new model for the rest of the country.

You can find out more about the Building with Nature project here and current events here.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.