Rethinking Water Management for a Changing Climate in SIDS

Water resources in Small Island Developing States (SIDS) present unique and complex challenges. Nearly all small islands are already experiencing water stress, defined as annual water supplies below 1,700 m3 per person. Paradoxically, some SIDS have sufficient water resources to meet demand, but do not have the infrastructure, institutional frameworks, or capacity to close the gap between supply and demand.

Climate change impacts, including sea level rise, altered precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events, are increasingly exacerbating these challenges. Most climate change models indicate that the total annual rainfall levels for the Caribbean region will decrease by at least 10–20%, significantly straining available freshwater resources. Meanwhile, sea level rise around Papua New Guinea (7.0 mm annually) and the Caribbean (6.15 ± 0.5 mm annually) dramatically outpaces the global average of 2.8-3.5 mm per year. This accelerated increase drives saltwater intrusion into critical groundwater resources, contaminating drinking water sources and adversely affecting agricultural productivity—a particularly devastating impact for low-lying atolls where alternative water sources are scarce.

These compounding climate change impacts are exacerbated by rapid urbanization and growth in water-intensive industries such as tourism, irrigated agriculture, and industrial activity, leading to intense competition for land and water resources in SIDS. The sprawl of urbanization into upper watershed areas has resulted in higher peak flows, downstream flooding, and an overall decrease in base stream flows. In the Caribbean, this can be seen in areas such as Port of Spain in Trinidad and Castries in Saint Lucia.

Furthermore, tourism is a crucial driver of economic growth in many SIDS. However, tourists consume, on average, more than three times as much water as the local population per capita. This increased demand strains the local water supply during peak tourist seasons. This is especially challenging when the peak tourist season coincides with the dry season, as is the case with many destinations in the Caribbean.

SIDS face additional challenges related to ineffective water resource management systems and governance structures, compounding their existing environmental and resource constraints. These include inefficient service quality, inadequate upkeep and operation of current water infrastructure systems, and deteriorating water infrastructure. Additionally, there are significant concerns regarding unaccounted-for water loss and the treatment of wastewater.

For example, non-revenue water (NRW) is a critical resource challenge for SIDS. NRW includes all the water produced but lost in the distribution system or not paid for by consumers. Well-performing water utilities have levels of NRW below 30%, but the average NRW for SIDS is 46%, with some reaching as high as 75%. Again, a 2017 report from the United Nations shows that high-income countries treated up to 70% of grey water for reuse, whereas in SIDS, untreated water represents 84% of their industrial water footprint. A further challenge for SIDS is the inability to quantify their water resources, making it difficult to undertake solid short- and long-term planning.

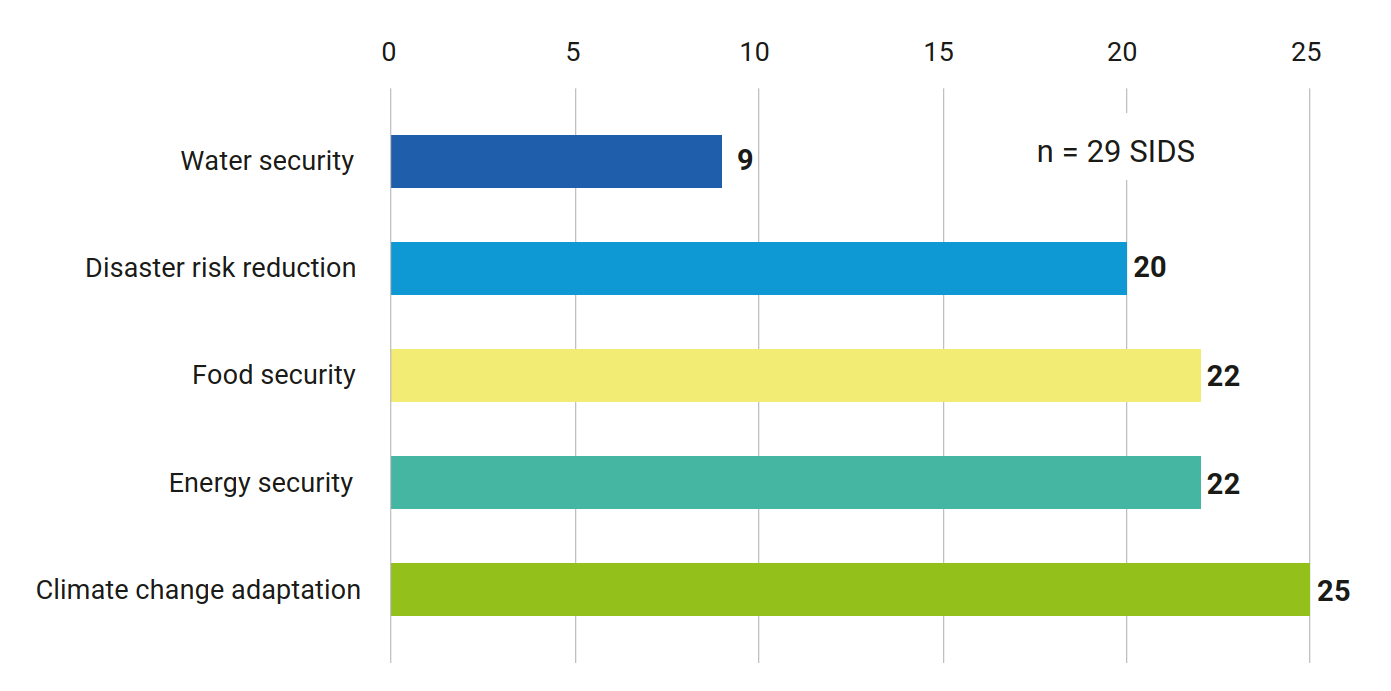

While problems concerning freshwater resources continue to grow in the 39 SIDS, only 9 have substantively included water security in their economic development plans (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Selected Strategic Priorities Treated in SIDS National Development Plans

Source: UNCTAD (2021). This work is available through open access, by complying with the Creative Commons license created for intergovernmental organizations, at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/.

Addressing the Water Challenge in SIDS

Addressing water challenges in SIDS requires a holistic approach that integrates climate change adaptation and resilience-building strategies, while planning for sustained growth in economic and social development.

For instance, Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) is now considered a holistic planning, participatory, and implementation process to determine how to meet society’s long-term needs for water. However, existing IWRM guidelines and tools rarely address the unique context of Small Island Developing States (SIDS), hindering effective implementation in these regions.

Financial constraints and inadequate mobilization of financial resources for water resources management are also major issues hampering capacity building and technical investigation essential for the design and implementation of IWRM strategies and frameworks.

Even so, in recent years, several regional initiatives in the Caribbean and the Pacific have emerged to support IWRM, such as the Global Water Partnership – Caribbean, the Consortium of CARICOM Institutions on Water, and the Pacific Integrated Water Resources Management Programme.

Other recommended policy actions include:

- Strengthening institutional capacity for water management, including improved data collection and monitoring systems. State-owned enterprises need to have greater autonomy in the decision-making process and in executing their duties without undue political inference.

- Exploring hybrid water distribution technologies and management systems, including rainwater harvesting. Viewing the water system of islands as a hybrid distributed system can allow for lower-cost alternatives to water management due to smaller infrastructure (from rainwater harvesting systems) and reduced energy, operations, and maintenance costs.

- Investing in climate-resilient technologies, including upgrading water storage/distribution and renewable-energy-based desalination. Using renewable energy can help reduce the cost of desalination by lowering fossil fuel requirements. Desalination systems based on reverse osmosis powered by photovoltaic or concentrated solar power can address the vulnerability of existing water systems and the cost of water on islands in many ways.

- Improving wastewater treatment. It is estimated that only about 5% of the wastewater collected in the Caribbean is properly treated and disposed of. Although a major problem in SIDS, wastewater can be seen as an untapped resource for treatment and reuse in industrial applications or agriculture. In July 2024, Barbados received $40 million in support from the Inter-American Development Bank to expand its reclaimed wastewater and establish a policy for water reuse.

To strengthen their resilience, SIDS must adopt risk-informed approaches when developing water infrastructure to meet growing needs. This requires integrating climate science to assess potential impacts throughout project lifecycles. Key strategies include locating new infrastructure away from vulnerable coastal zones and designing redundant, self-sufficient distribution systems that can withstand localised failures. These proactive measures will help ensure water security despite increasing climate challenges.

Written by Chandrahas Choudhury based on chapter ‘Water’ by Farah Nibbs (University of Maryland)

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.