This is how Singapore plans to save itself from rising seas and extreme weather

Climate change poses an existential threat to Singapore – a low-lying, tropical island at the mercy of rising sea levels, extreme weather and soaring temperatures. There’s no time to lose – which is why the country’s government is putting an ambitious plan into action to prepare for these threats.

T

he impacts of climate change will not be distributed equally around the world. For some of us, its effects will mean changes to the way we live; for others, the threat is existential.

Singapore counts itself among the latter. Climate change is a “life and death” matter for the country, according to its Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong in a speech he gave in August this year. “Everything else must bend at the knee to safeguard the existence of our island nation,” he said.

Climate change poses three main risks to Singapore. Firstly, as a low-lying island the country is vulnerable to rising sea levels; secondly, it will be hit with higher daily average temperatures; and lastly, Singapore expects longer and more frequent periods of intense rainfall interspersed with prolonged droughts.

These are urgent threats. Singapore, according to the country’s own meteorological service, is heating up twice as fast as the global average, and is already 1˚C hotter than it was in 1950. But the government has a plan. It is pledging to spend $72 billion within the next 50-100 years in order to adapt to the worst effects of climate change – which, in Singapore’s case, means ensuring the country’s very survival.

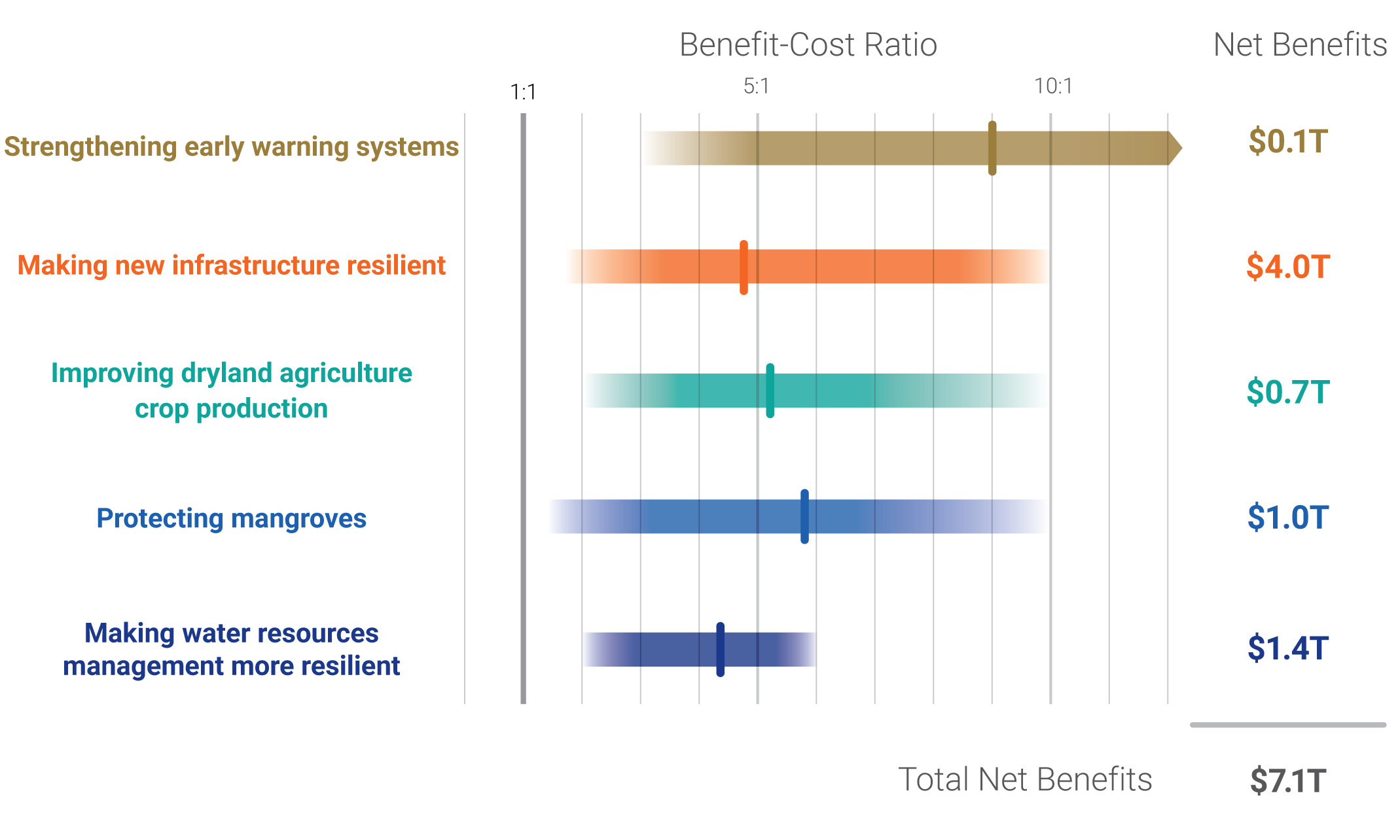

A new report from the Global Commission on Adaptation, Adapt Now: A Global Call for Leadership on Climate Resilience, calls for an investment of $1.8 trillion globally from 2020 to 2030, and estimates that this could generate $7.1 trillion in total net benefits.

Keeping cool

To counter the increased risk of flooding as the sea level rises, Singapore is looking at creating polders – tracts of land reclaimed from the sea, surrounded and protected by a system of dikes and pumps – along its eastern coastline. As well as providing the country with more land to develop, the polders would be able to absorb huge quantities of floodwater, protecting the hinterland beyond.

One possibility is to reclaim a series of small islands off Singapore’s eastern coastline; these could be connected by barrages to create a freshwater reservoir, which would have the added benefit of helping sustain the city’s water supplies in times of drought.

Rising sea levels could also threaten Singapore’s food supply, 90% of which is imported. Climate change will have a negative effect on rice yields in Asia, according to one recent study; in Singapore’s case, flood damage to low-lying rice fields in neighbouring countries such as Thailand or Indonesia, for example, could lead to empty shelves in the island nation’s shops. To bolster its food security, the Singaporean government aims to increase the proportion of food grown locally to 30% by 2030, using technologies such as vertical farming to maximise output.

Rising temperatures could also have a severe effect in the years to come. Singapore is a hot and humid corner of the world, a fact compounded by the city’s propensity to trap heat from the sun and human activity – a phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect. The difference in temperature between downtown Singapore and the city’s rural outskirts is around 4˚C and can exceed 7˚C; this can make life outdoors uncomfortable, dissuading residents from getting fresh air and exercise and increasing the use of air conditioners which pump warm air out into the city, making the problem worse.

In 2017, a project funded by Singapore’s National Research Foundation called Cooling Singapore was launched with the aim of finding and putting in place countermeasures that could help alleviate the problem of rising temperatures. The project is exploring a host of ideas, from increasing the amount of urban vegetation and shade to using modern materials to cool down the city’s pavements and rooftops.

Transportation is another area being considered by the project; internal combustion engines generate a lot of heat, which means moving the city’s travellers onto public transport and into electric vehicles could help to cool things down.

The urban heat island effect also increases the risk of heavy rainfall – something that climate change, too, will exacerbate. In preparation, Singapore is also looking at strengthening its existing flood defence systems and building new infrastructure, including new water retention tanks and increasing the capacity of the city’s drains.

Together, this is a massive and expensive programme of public works and preparation – but as Prime Minister Lee said, it is now an imperative. “We must make this effort,” he said in his speech “Otherwise one day, our children and grandchildren will be ashamed of what our generation did not do.”

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.