New York’s rooftop farms provide fresh local produce – and help stop a sewage problem

Sewer systems around New York can become overwhelmed during heavy rainfall. The creators of this rooftop farm think they have the answer.

H

igh above the streets of New York, more than 36 tonnes of organic vegetables are grown every year. And the farms that produce them aren’t just feeding residents – they’re helping to stop sewage polluting the city’s rivers too.

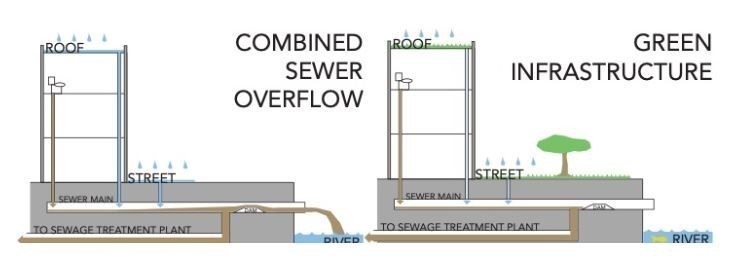

Covering a total of 2.3 hectares (5.6 acres), the farms sit on top of three historic industrial buildings. Their soil is just 25 cm (10 inches) deep, but it absorbs millions of litres of rainfall each year – water that would otherwise flush straight into the city’s drains.

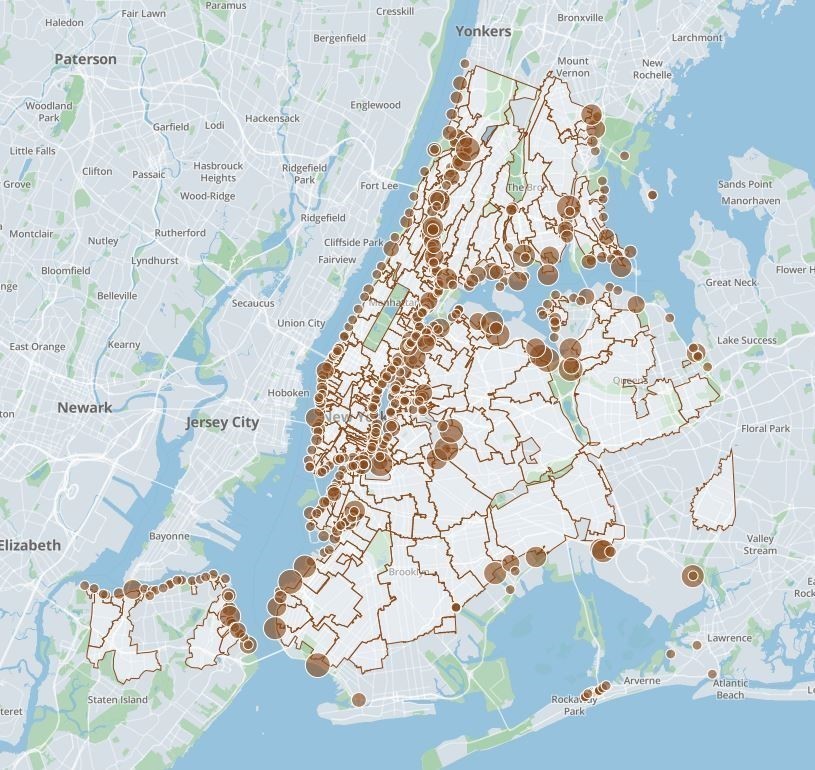

New York has long had a problem with what is known as Combined Sewer Overflow, where rainwater inundates water treatment plants causing the sewers to overflow directly into the Hudson and East River.

Sewer systems around New York can become overwhelmed during heavy rainfall. Image: Open Sewer Atlas NYC

Growing business

The city has made progress in recent decades, spending $45 billion since the 1980s on wastewater treatment to reduce discharges into waterways. But with more than 70% of its area paved and upwards of 8 million residents, the problem still occurs when it rains heavily.

Brooklyn Grange, which operates the three rooftop sites, built its first farm in 2010. It broke even in its first year, moved into profit two years later and now employs 20 full-time and 60 seasonal staff.

Its founders believe commercial urban agriculture can help cities become cleaner and greener. And they measure their success against a “triple bottom line” – profit, the environment and impact on people.

Image: Brooklyn Grange

A buzzing project

Green roofs help urban areas reduce the heat that otherwise radiates on summer nights from conventional rooftops. That not only helps to make the city cooler in summer but also reduces the amount of energy needed to keep the buildings cool.

The rooftop farms use waste food to produce compost. Half their produce is sold to restaurants and they run two weekly markets and deliver locally through a community-supported agriculture scheme, which connects farmers directly to consumers. They are home to 40 beehives, too.

The farms have so far hosted 50,000 young people on educational visits to learn about sustainable city farming. They run public courses on everything from sustainable dye-making to making hot chilli sauces. They host yoga classes and even weddings.

The company has now expanded into designing and building mini farms and wild flower gardens for private clients across the city.

Almost 70% of the global population is predicted to live in cities by 2050. And while cities drive the global economy, they are also responsible for three-quarters of global CO2 emissions.

So projects like these will become ever more important, according to the World Economic Forum Global Future Council on Cities and Urbanization, if urban areas are to meet targets such as those set out in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement on climate change.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.