Building Resilience from the Ground Up: Risk-Informed Planning in Congo and Burundi

Temporary flood protection measures in Brazzaville (November 2025. Photo credit: Ivan Bruce)

A Neighbourhood-Centred Approach to Urban Resilience

Across rapidly urbanising cities in the Republic of Congo and Burundi, many communities face recurring flood risks, land degradation, and erosion. These hazards are compounded by informal settlement patterns, poor infrastructure, and limited financial support. Yet, within these communities lies an untapped strength: the local knowledge, ingenuity, and commitment of residents who are already implementing their own resilience measures – clearing blocked drains, building makeshift barriers, or rerouting household wastewater.

Recognising the value of this local knowledge, the Global Center on Adaptation (GCA), in partnership with the World Bank, engaged JBA Global Resilience to deliver a risk-informed planning assignment to support climate-resilient neighbourhood development.

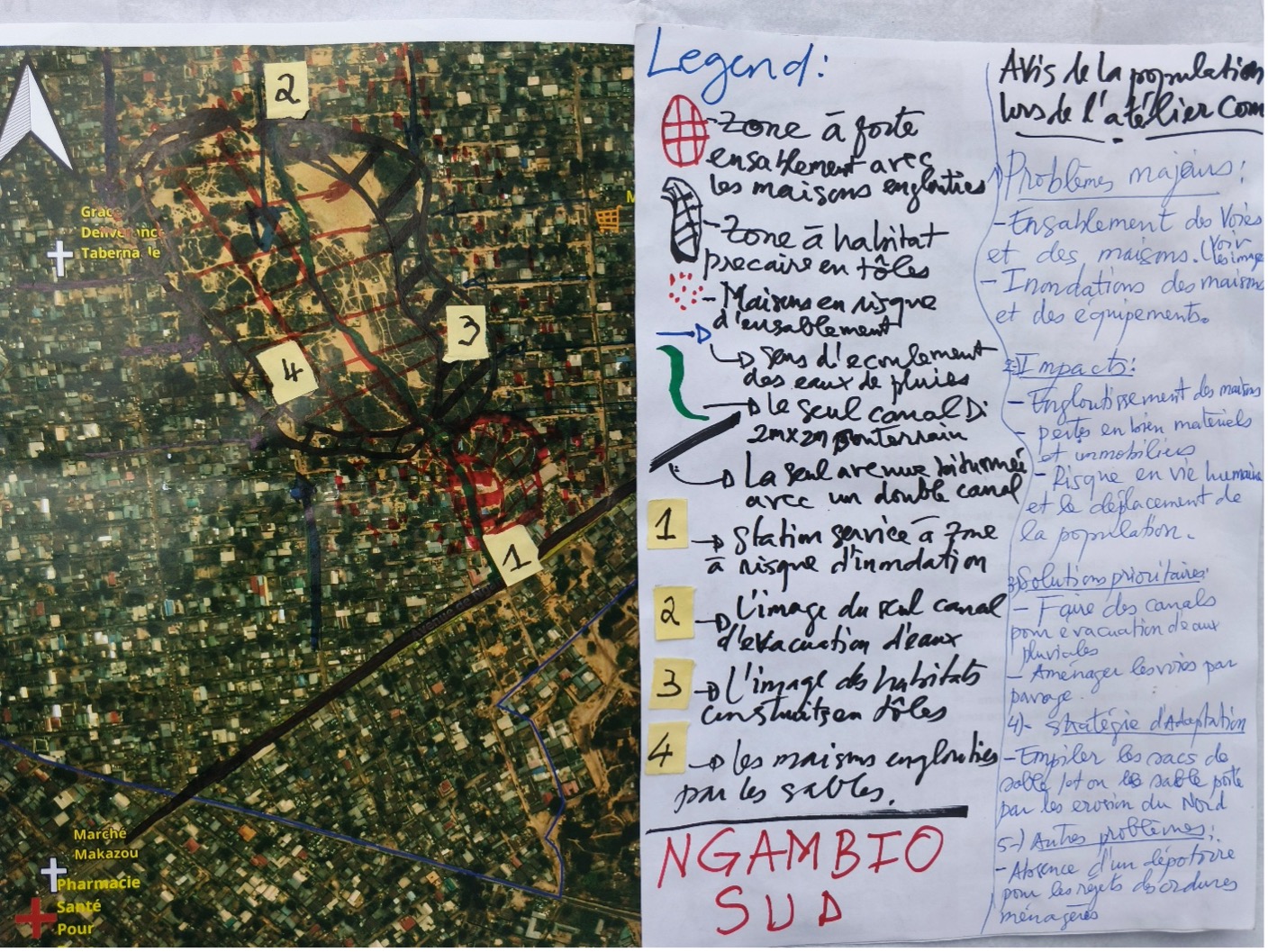

This initiative focused on the development of Community Resilience Spatial Frameworks (CRSFs) for two vulnerable neighbourhoods in each country: Ngambio (Brazzavile) and Tchiali (Pointe-Noire), Republic of Congo, and Buterere and Gatunguru in Bujumbura, Burundi. The CRSFs are planning tools designed to help neighbourhoods identify, prioritise, and coordinate resilience actions.

At the heart of this assignment was a bottom-up methodology that prioritised community engagement as the foundation of all planning efforts. The CRSFs were not simply technical exercises. They were built through collaborative and iterative dialogues with residents, civil society groups, and municipal authorities – designed to ensure that resilience planning was grounded in the lived realities of those most exposed to climate risks.

Transect walk with community members and consultancy team in Tchiali. (November 2025. Photo credit: Alain Phe)

Walking with Communities to Understand Risk and Resilience

A core element of this process involved extensive community engagement missions, where the project teams walked the streets and ravines of each neighbourhood with local representatives. These transect walks served as real-time diagnostics, allowing the teams to validate existing risk data, witness first-hand the visible impacts of seasonal flooding and poor drainage, and hear directly from the people experiencing these challenges.

These exercises allowed for real-time dialogue on flooding impacts, contributing factors such as blocked culverts and unplanned construction, and the challenges faced by vulnerable households.

What emerged was not only a clearer picture of the physical risks but also examples of community-led resilience:

- Ngambio: residents organised informal waste patrols to clear drainage channels.

- Tchiali: rudimentary erosion control trenches were dug with basic tools.

- Buterere: households adapted roofing to redirect stormwater.

These locally developed solutions – modest but practical – were born out of necessity and demonstrated both adaptive capacity and urgency. Rather than replacing these efforts, the project aimed to recognise, enhance, and integrate them into a broader framework for risk reduction.

Participatory community mapping workshop in Ngambio. (November 2025. Photo credit: Ivan Bruce)

Community-map developed in Ngambio of climate risk and potential solutions. (November 2025. Photo credit: Claude Mahoungou)

From Insights to Action: Defining Short and Medium-Term Measures

From these observations and discussions, the CRSFs were shaped. Not as static technical reports, but as practical planning tools, intended to be community-owned and to guide the systematic implementation of climate resilience actions.

Each CRSF outlines a comprehensive list of structural and non-structural interventions that were discussed, prioritised, and refined with the community and local authorities. These actions are grouped into two categories: short-term (0–3 years) and medium-term (3–5 years), allowing for progressive implementation based on urgency, feasibility, and resource availability.

Short-term actions were often enhancements of existing community efforts, such as formalising routine drain cleaning, setting up communication protocols for flood alerts, or designating temporary safe zones in churches or schools. Medium-term actions involved more capital-intensive interventions, including constructing wetland buffers, improving stormwater channels, or integrating resilient road surfacing.

Importantly, the prioritisation of actions was not arbitrary. A multi-criteria framework – considering impact, feasibility, community preference, and alignment with broader resilience objectives – was applied to ensure the most relevant actions were advanced.

The Role of the CRSFs: Guiding Locally-Owned Resilience Planning

The CRSF is not a conventional plan. It is a community-owned spatial framework designed to help translate risk analysis into concrete actions. Each CRSF offers detailed spatial guidance, aligns with municipal planning tools (such as the Plan Local d’Urbanisme or PLU), and identifies zones of priority intervention. By anchoring resilience actions to administrative units like quartiers and arrondissements, and incorporating geospatial data, the frameworks are designed to be both implementable and monitorable.

At the same time, the CRSFs are intended to be flexible and adaptable. They serve as working documents that communities, NGOs, and local governments can return to, update, and expand over time. By aligning with existing policies, and linking to larger-scale investments, the CRSFs can serve as bridge tools that connect grassroots action with institutional urban planning.

Map developed by JBA to show prioritised community measures for Buterere. (December 2025. Image rights: JBA Global Resilience)

Resilience Is a Portfolio Approach, Not a Silver Bullet

Crucially, the CRSFs do not propose a single ‘silver bullet’ solution. Instead, they advocate for a holistic portfolio of measures, recognising that resilience requires a combination of hard infrastructure, community organisation, improved governance, and behaviour change. By balancing structural interventions (like improved drainage or flood walls) with non-structural approaches (like preparedness plans, handbooks, and monitoring systems), the CRSFs offer a flexible yet comprehensive roadmap tailored to the realities of each neighbourhood.

This assignment has shown that risk-informed planning must start by listening to those most affected. It must be participatory, place-based, and practical. The CRSFs developed in Ngambio, Tchiali, Buterere, and Gatunguru offer replicable models that demonstrate how bottom-up planning – grounded in lived experience and backed by technical expertise – can lead to tangible, community-driven climate resilience.

Looking ahead, the lessons from this assignment offer replicable models for other cities in Sub-Saharan Africa facing similar climate risks. By embedding community knowledge, field-based observation, and multi-stakeholder collaboration into resilience planning, the CRSFs demonstrate that meaningful climate action starts at the neighbourhood level. Empowering communities to design, prioritise, and implement solutions not only strengthens their capacity to adapt – but also makes urban resilience planning more just, inclusive, and ultimately more effective.

Written by Ivan Bruce, Principal Disaster Risk Management Specialist at JBA Global Resilience

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.