Countries around the world are looking to the Netherlands to help them deal with flooding and water crisis. Here’s why

The Netherlands’ Delta Programme is helping the country plan for future water-related problems and disasters, while responding to the already present threats of flooding and water insecurity.

W

ith a third of its land below sea level, the Netherlands is extremely vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Rising sea levels, torrential rain and soil subsidence put 60% of the country at risk of flooding, including major cities.

But the country is taking action: every year it spends €1.3 billion on a climate change adaptation plan. The Delta Programme wants to make the Netherlands better able to cope with weather extremes by ensuring its flood risk management, freshwater supply and spatial planning are climate-proof and water-resilient by 2050.

The aim is to “prevent a disaster, rather than devise measures on the aftermath” and the average annual budget is presently protected until 2032. The programme has identified a range of long-term and short-term strategies, flexible solutions that can be deployed or changed as new insights and circumstances emerge. This approach is known as “adaptive delta management” – taking the right steps now that still leave future options open.

The water supply in the centre of the country, for example, is being gradually and flexibly expanded with additional water from a nearby river and canal. This helps to fight salinisation and drought now, but also prepares it for increased demand on the water supply in the future. The expansion is due for completion by 2021.

On the right track

As part of this flexible approach, the government reviews the programme each year to make sure it’s on the right track. The latest 2020 update concludes that it is: the country has demonstrated its increasing ability to cope with prolonged drought; improvements to dykes, which help reduce the risk of flooding, are keeping pace with the required weekly average of one kilometre up to 2050; and preparations are underway for the scheduled six-year review in 2021 of the strategies initially set out in 2015, in order to accommodate new climatic, economic or demographic developments.

The development of programmes to produce an adaptive response to a potentially rapid increase in sea level beyond 2050, including reducing the uncertainties about developments in Antarctica and their impact on sea levels, and to encourage joint national and regional management of river systems have also made good progress.

“Government authorities are taking measures to minimise the damage caused by heat stress, waterlogging, drought and urban flooding, bearing such issues in mind in the construction of new residential areas and industrial estates, in the renovation of existing buildings, in the replacement of sewer systems, and in road maintenance work,” says Cora van Nieuwenhuizen Wijbenga, Dutch Minister of Infrastructure and Water Management.

“This is a tasking that needs to be addressed in spatial policies at the national, provincial, and municipal scale levels.”

Exporting knowledge

The Delta Programme and the Dutch approach to delta and flood management and climate change adaptation is becoming an export product. Indeed, the Netherlands has a special envoy for international water affairs, who travels the world to offer Dutch expertise or assistance to countries with water-related problems.

Vietnam was the first country to adopt the initiative as part of the Mekong Delta Plan. The similarities between the Mekong and Dutch river deltas – densely populated, fertile, major economic centres, vulnerable to flooding – meant the programme could be adapted to provide a long-term vision for the region up to 2100 and short-to-medium-term measures covering the next 30 years, as well as recommendations on how to legislate and finance delta management.

“The challenge in Vietnam is not to prevent flooding, because floods provide a major contribution to the viability of the system,” said Melanie Schultz van Haegen, then Minister of Infrastructure and the Environment, at its 2013 launch.

“What matters here is to deal with the high annual discharges as sensibly as possible, and with salinisation of farmland, drought, insufficient irrigation capacity and threats to valuable ecosystems. That calls for a comprehensive approach – and that is what the Netherlands is renowned for.”

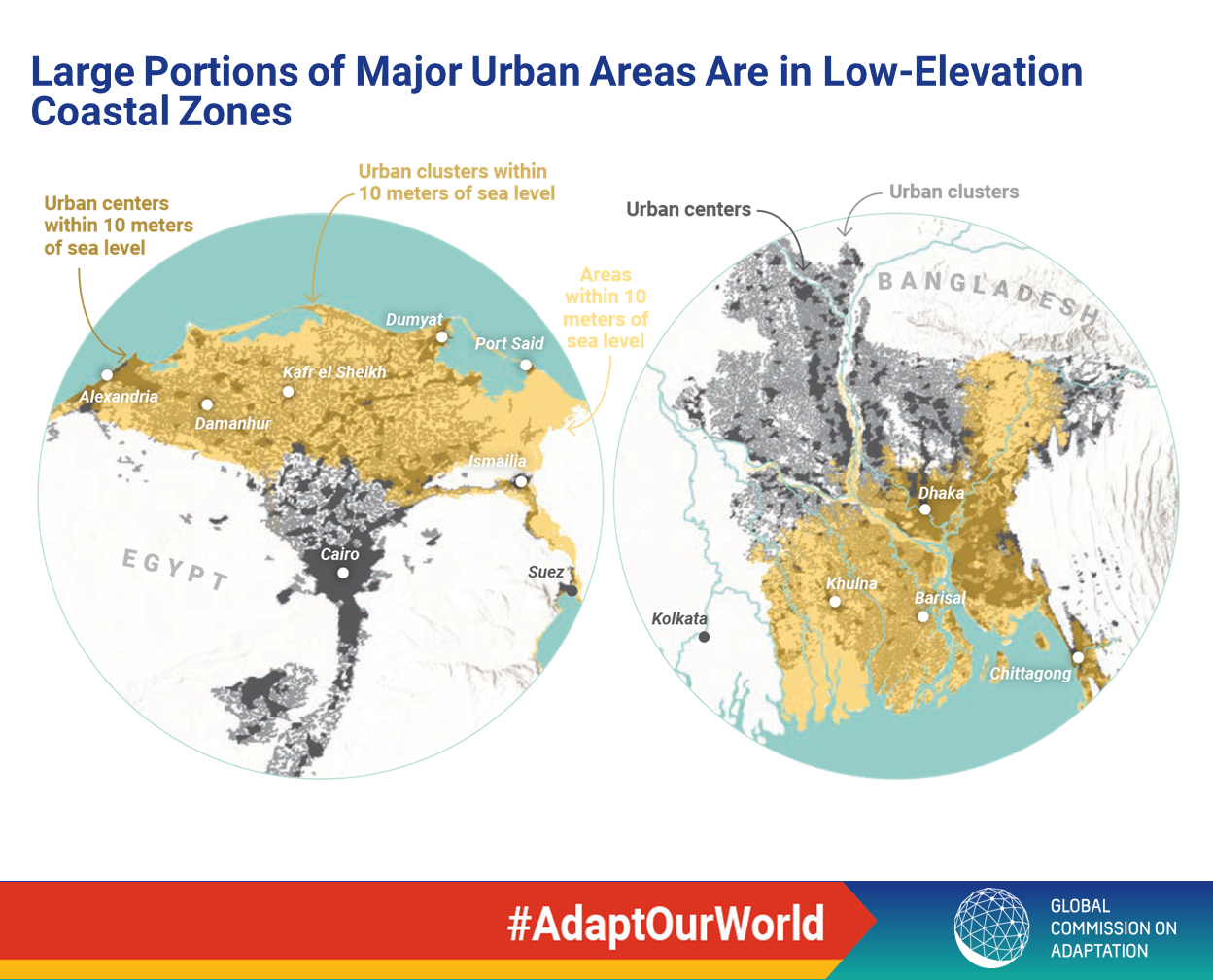

In 2018, the Bangladeshi government announced its Delta Plan (BDP2100), inspired and led by Dutch experts and efforts. Much like the Delta Programme it includes policy frameworks and regional adaptive strategies for Bangladesh. It was launched with 80 potential projects covering steps such as flood protection, freshwater security and the adaptation of cities and infrastructure to climate change, as well as plans for financing and to enshrine the programme in law, as it is in the Netherlands.

“Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina herself said that Bangladesh will become a developed country by 2041. BDP 2100 took birth to give shape to that vision. Everyone must work to implement it,” says Khalid Mahmud Chowdhury, Bangladesh’s State Minister for Shipping.

The Netherlands is also helping Myanmar and Argentina to establish Delta management plans for the Irrawaddy Delta and Paraná Delta respectively. In Chile, Peru, Mexico and Canada, it is helping with plans to make cities and regions less vulnerable and more resilient to flooding.

“For us, water is energy, life, food, cities,” says special envoy Henk Ovink. “The rest of the world, through climate change, urbanization, growth, and prosperity, is rapidly starting to understand our way of life.”

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.