Equitable land restoration in rural India means listening to every level of the community

Climate change is exacerbating extreme weather and the poor condition of land already damaged by natural or human events. One method applied in Sidhi, India shows a way towards restoration.

I n Sidhi, a resource-rich but largely impoverished district in central India, most people depend on forests and the land to survive. That makes Sidhi typical of the dozens of underdeveloped landscapes in India and worldwide. Changes in forest composition, land degradation, rising temperatures and desertification have made it harder than ever for people there to thrive.

What can local people and governments do to mitigate these vulnerabilities?

A new report from WRI India found that the district could economically and ecologically benefit from landscape restoration, a set of nature-based solutions to climate change that bring vitality back and improved productivity. When implemented at scale in Sidhi, restoring land by growing trees and protecting forests could conserve biodiversity, improve water recharge, sequester carbon, enhance rural livelihoods and spur rural development. It’s a nearly $19 million opportunity that this rural district can’t afford to miss.

A people-centric methodology

We knew that land restoration could benefit people in Sidhi economically and ecologically. But we wanted to ensure that its primary beneficiaries would be tribal and Indigenous peoples, women and other marginalized groups that are heavily dependent on forests, the commons and unproductive land for their sustenance.

To achieve that goal, we adapted the Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology (ROAM) to include criteria that go beyond the environmental benefits of restoration. That allowed us to assess the impact of restoring land on the economy, land tenure and resource rights.

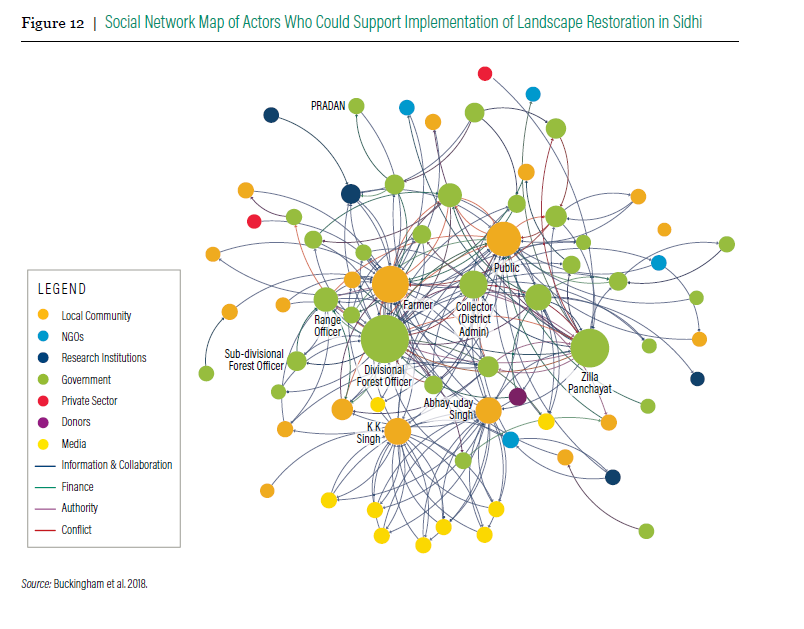

We didn’t stop there. We mapped the district’s social landscape by identifying the key people and organizations that govern the flow of information and funds, hold authority and spur and mediate conflict.

This analysis helped us understand that people’s social status influences how they want to benefit from restoration. We found that while women and members of India’s marginalized Scheduled Tribes and Castes implement restoration, they are seldom key decision-makers.

Privileged upper-caste men in Sidhi tend to prioritize regulatory services like protecting biodiversity and controlling erosion. Poor, marginalized Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe men and women, though, prioritized provisioning services like fuelwood for their homes, fodder for their livestock and non-timber forest products like fruit for consumption.

Our analysis makes one thing clear: we need to consider the complex people-environment relationships that govern land restoration projects. These insights can help local decision-makers build more inclusive systems to manage land that cut through power imbalances and maximize sustainable economic opportunities that create value for the most marginalized people.

Economic and environment potential

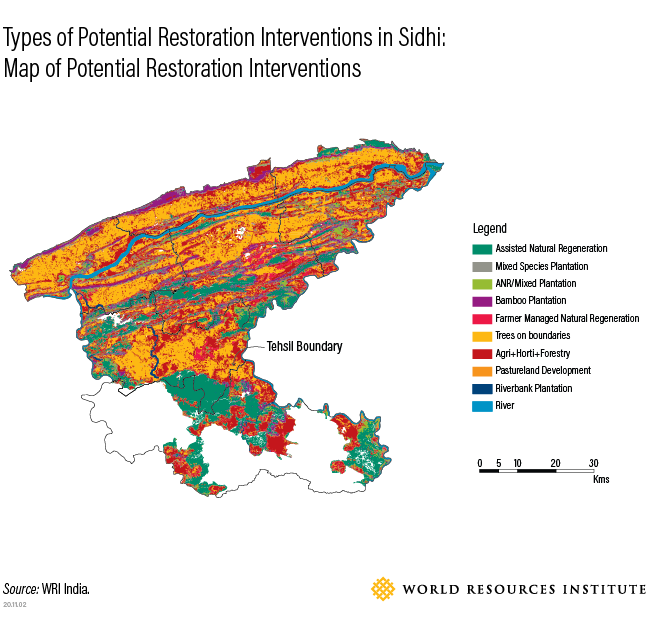

These social insights are especially important because the economic and climate opportunities are so large. Three-quarters of Sidhi’s land could benefit from eight different types of tree-based restoration, such as growing trees on boundaries, helping trees naturally regenerate and creating sustainable orchards on farms (agro-horti-forestry).

Examples of land restoration success already exist. For instance, local communities have already restored more than 2,400 hectares (5,930 acres) of bamboo forests over four years in partnership with the Forest Department. However, achieving the full potential will require some serious investment to grow nearly 40 million tree saplings in two years (requiring 3.75 million working days). Thousands of people could earn wages of a total of 710 million rupees ($10 million) and an additional 592.3 million rupees ($8.46 million) from selling saplings to projects. This is in an area where the average daily wage is between $2 and $4.

In five to seven years, this investment could also create over 3,000 micro-enterprises that employ 30,000 people — including women, youth and landless people — to grow, harvest, process and sell high-value tree crops like bamboo for furniture and wood and jackfruit, moringa and Indian Gooseberry for cooking.

Restoring the district’s forests could also sequester more than 7 million metric tons of carbon over 10–20 years by growing native trees. The opportunity is massive across India: 140 million hectares (346 million acres) of land could benefit from forest protection and landscape restoration, safely storing up to 4.3 gigatonnes of above-ground carbon in vegetation by 2040. That’s more than India emitted in all of 2018.

Implications for wider restoration approaches

The Sidhi district is typical of India’s rural landscapes. More than 700 million people across the country depend on forests and agriculture for sustenance. And over 250 million people, including tribal/indigenous communities, women and marginal farmers depend on forests for fuelwood, fodder, food security and non-timber forest products.

All of these people are vulnerable to the effects of climate change, which could reduce agricultural incomes by up to 25% annually, according to the Economic Survey of India 2017-18. This will leave more than 50% of India’s workforce vulnerable and its largely rural workforce in extreme distress. Continuing business as usual is not an option.

Investments in landscape restoration throughout India can deliver a reliable development path that improves the lives of women, unemployed youth, landless people and small and marginal landholders. Local people should be at the center, designing and implementing landscape restoration projects. By adjusting ROAM and mapping the social landscape, our analysis offers an example that researchers in landscapes around the world can use to boost inclusion and participation.

What we learned in Sidhi brings us closer to unravelling the economic potential of nature-based solutions and the green economy across India and around the world.

To learn more, see the full report, Restoring Landscapes in India for Climate and Communities

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.