Green, blue, brown and white roofs – what are they and why do we need them?

The trend for green roofs is growing, but there are other varieties: brown, blue and white. Here’s a guide to the different types of environmentally friendly rooftops.

F

rom the middle of November 2019, all new commercial or residential buildings in New York City must be topped by a ‘green roof’ or solar panels. The city is the latest in a string of cities around the world to attempt to adapt to climate change and other environmental concerns, such as declining wildlife, by making use of the space above our heads.

In the US, Chicago, Denver and San Francisco are among the cities that have already passed regulations to require or incentivise green roofs. In Germany, which claims credit for the modern green roof technology, there were around 86 million square metres of green roofs in 2014, with about eight million more being added each year. The Namba Parks retail and office in Osaka, Japan, has an eight-level rooftop garden.

The trend for green roofs is growing but the roofs don’t actually have to be green. They could be brown, blue or even white. Here’s a guide to the different types of environmentally friendly rooftops, and what they are used for.

The green roof

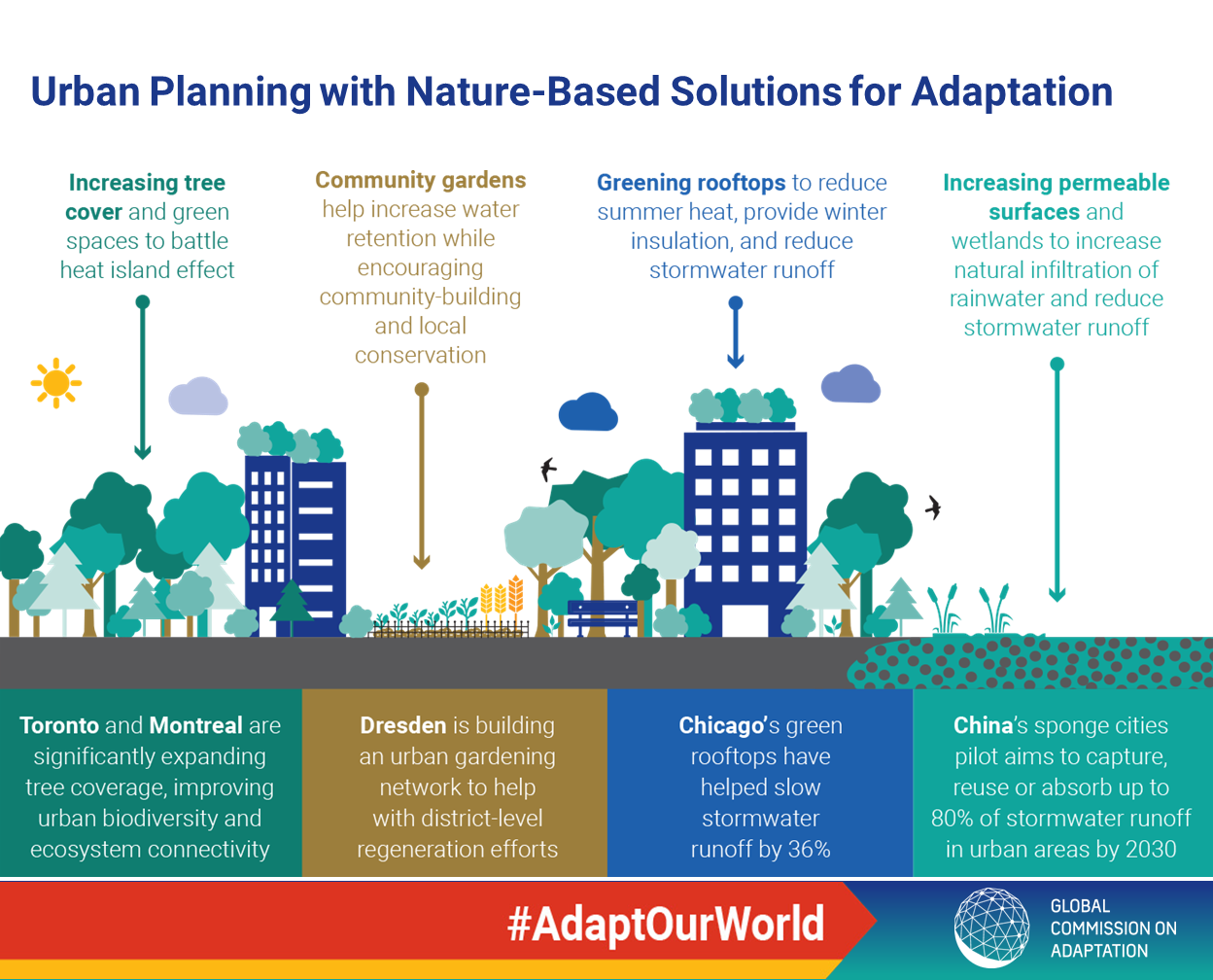

A typical green roof is one that is covered in vegetation. This could be a thin layer of low-maintenance plants, known as an extensive roof, or it could be a thicker layer, which requires similar maintenance to a garden, known as an intensive roof. As well as making an urban area look better, green roofs serve a range of purposes. They absorb CO2, helping in the fight against climate change, and act as an insulating layer on the building, reducing demand for heat in the winter. In the summer they help to keep the building cool.

However, the benefits don’t stop there. Green roofs act as a habitat for all kinds of wildlife. Insects, butterflies, bees and birds are all decreasing in urban environments but green roofs can help to boost their numbers. And, finally, they are good for human beings too. Green roofs filter pollutants out of the atmosphere and, by increasing the amount of green space in cities, can have a positive impact on mood and wellbeing.

White roofs – nothing new in Greece. Photo by Loveombra/Pixabay

The blue roof

More than half the world’s population, 55 per cent, lives in urban areas and, according to the UN, that number will rise to 68 per cent by 2050. As our urban areas grow, we replace fields and forests with concrete and brick. The result is that there is less soft ground to absorb rainwater and more flooding. Not only that, but the ‘runoff’ water picks up pollutants and carries them into waterways, along the way it also causes soil erosion and puts strain on drainage infrastructure.

A blue roof helps deal with these problems by storing the water or restricting the speed at which it can run off. The water can be ‘harvested’ and used to irrigate a green roof or for flushing toilets in the building below. This reduces demand on the mains water supply. Like green roofs, blue roofs can also be used to cool urban environments. They are increasingly popular in new buildings. For example, the $54 million renovation of The Last Hotel, in St Louis, which was completed in 2019, includes a blue roof.

The brown roof

A variation of the green roof is the brown roof, which is focused on biodiversity to compensate for the loss of brownfield habitat caused by construction. Soil and rubble from construction are typically used as the substrate for the brown roof, with the vegetation selected to match local species and targeted at encouraging particular habitats. The brown roof of the Laban Dance Centre, in Deptford, south London, was installed in 2002 and inspired the creation of the Living Roofs campaigning organisation.

The white roof

In the Mediterranean, houses have had white roofs for centuries. Painting a roof white reflects up to 85 per cent of the sunlight that hits it, keeping the building cooler and reducing the need for air conditioning. And because they don’t hold heat, they don’t warm the air above them either, which reduces the ‘urban heat island’ effect. A study of cool roofs in Chicago found that the air above them was seven-to-eight degrees cooler. White roofs perform better than green roofs at reducing heat. However, they don’t bring the benefits to wildlife or rainwater that come from green roofs and their variations.

In a recent article for The Conversation, Michael Hardman and Nick Davies, of the University of Salford, said that although green roofs are becoming far more common, there needs to be increased buy-in from both the public and private sector. Investors and developers still need convincing. However, as pressure grows for more adaptive measures for climate change, it seems likely that green roofs will grow in popularity.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.