How AI could help us stay ahead of extreme weather

Extreme weather events are likely to become more powerful and frequent as the climate changes. Artificial intelligence might help societies be better prepared for the deluge and drought.

T

he European heatwave in the summer of 2019 was made 100-times more likely because of climate change, according to Friederike Otto, of Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute. Though extreme weather events have always happened, there is mounting evidence that human-driven climate change is increasing the likelihood and intensity of certain events, from hurricanes and heat waves, to floods and blizzards.

The effects can be devastating, which makes it important to be able to predict when extreme weather will strike. However, traditional weather forecasting, which uses supercomputers to create complex models of how the weather is likely to change, can struggle with extreme events. That is partly because we don’t fully understand the conditions that cause extreme weather and partly because the equations used to predict the weather might not be detailed enough.

Climate models generate thousands of gigabytes of data every day and scientists use algorithms to try to generate meaningful predictions. But, as Dr Otto points out, “while climate models are very good at representing how increases in greenhouse gases affect average temperatures, they are less good at representing more local extreme events”.

Now researchers are turning to artificial intelligence (AI) to generate better algorithms and find patterns hidden in the data.

Teaching the machines

Artificial intelligence is a catch-all term for a range of technologies covering everything from attempts to replicate human thinking to online chatbots that handle customer service inquiries. One subset of AI, machine learning, involves ‘teaching’ computers complex tasks by feeding them vast amounts of data. Some methods explain the rules to the computer and ask it to find similar examples. In ‘deep learning’, the computer is given the data and works out the rules by itself.

Whether the computer is identifying cancer from X-ray images or spotting extreme weather events from climate data, it can ‘learn’ from its mistakes, tweaking the algorithm to be more successful when it next examines the data. As it goes through this loop hundreds, or thousands, or times, it constantly refines the algorithm, often identifying patterns that humans cannot detect.

Given the success that this approach has had in everything from preventing credit card fraud to handling facial recognition at international borders, it is not surprising that it is now being applied to climate science. Major technology companies and academics are increasingly optimistic that AI can help to predict extreme weather events.

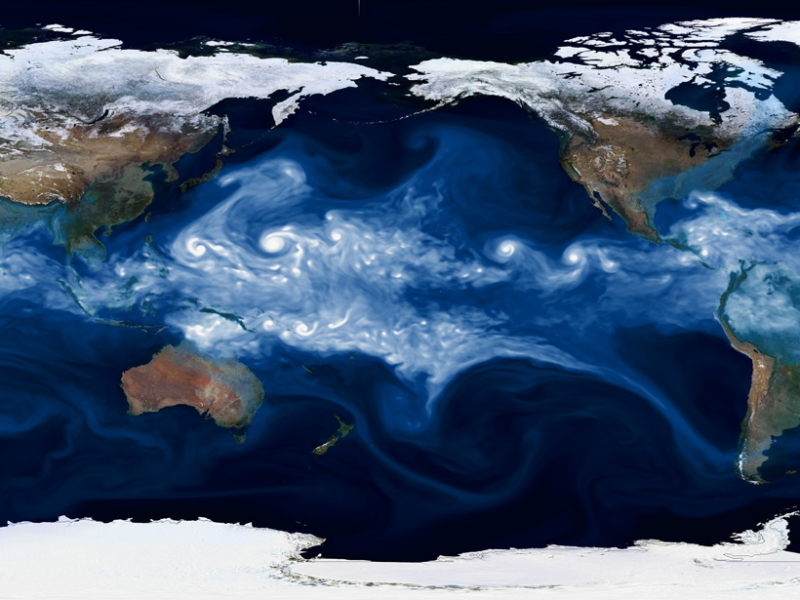

A high-resolution simulation generated by AI data that visualises the changes in the risk of extreme weather and climate. Photo by U.S. Department of Energy

Data crunching

Scientists at Rice University, in Texas, USA, have developed a computer system that has taught itself to predict extreme weather events. The system learned from hundreds of pairs of maps showing surface temperatures and air pressure, measured several days apart. Futurity reported that, “Once trained, the system could examine maps it had not previously seen and make five-day forecasts of extreme weather with 85 percent accuracy”.

In 2015 IBM acquired the Weather Company and launched the Atmospheric Forecasting System, which uses machine learning to predict events such as weather-related power outages up to 72 hours in advance. In China, the meteorological bureau in Shenzhen has been working with technology firm Huawei to build a cloud platform that uses AI to speed up deployment of prediction models.

There is still a long way to go. More, and better, data are needed, which is why scientists at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center in California have created a crowd-sourced database of extreme weather patterns. This is being used by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California to train a deep learning network to identify tropical cyclones and atmospheric rivers, air currents that transport water across the globe.

These are far from the only examples. Other tech giants are getting involved in weather and climate modelling, as are a range of startups. Better predictions will make it easier to adapt by managing resources better and mobilizing aid more quickly. Countries will be able to make contingency plans if they know that a drought is coming, for example, and insurance estimates will be more accurate for customers in areas that are at risk of floods.

Predicting extreme weather events is hard, but we can be certain that there are more on the way. AI could be our best hope of preparing for them.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.