Executive Summary

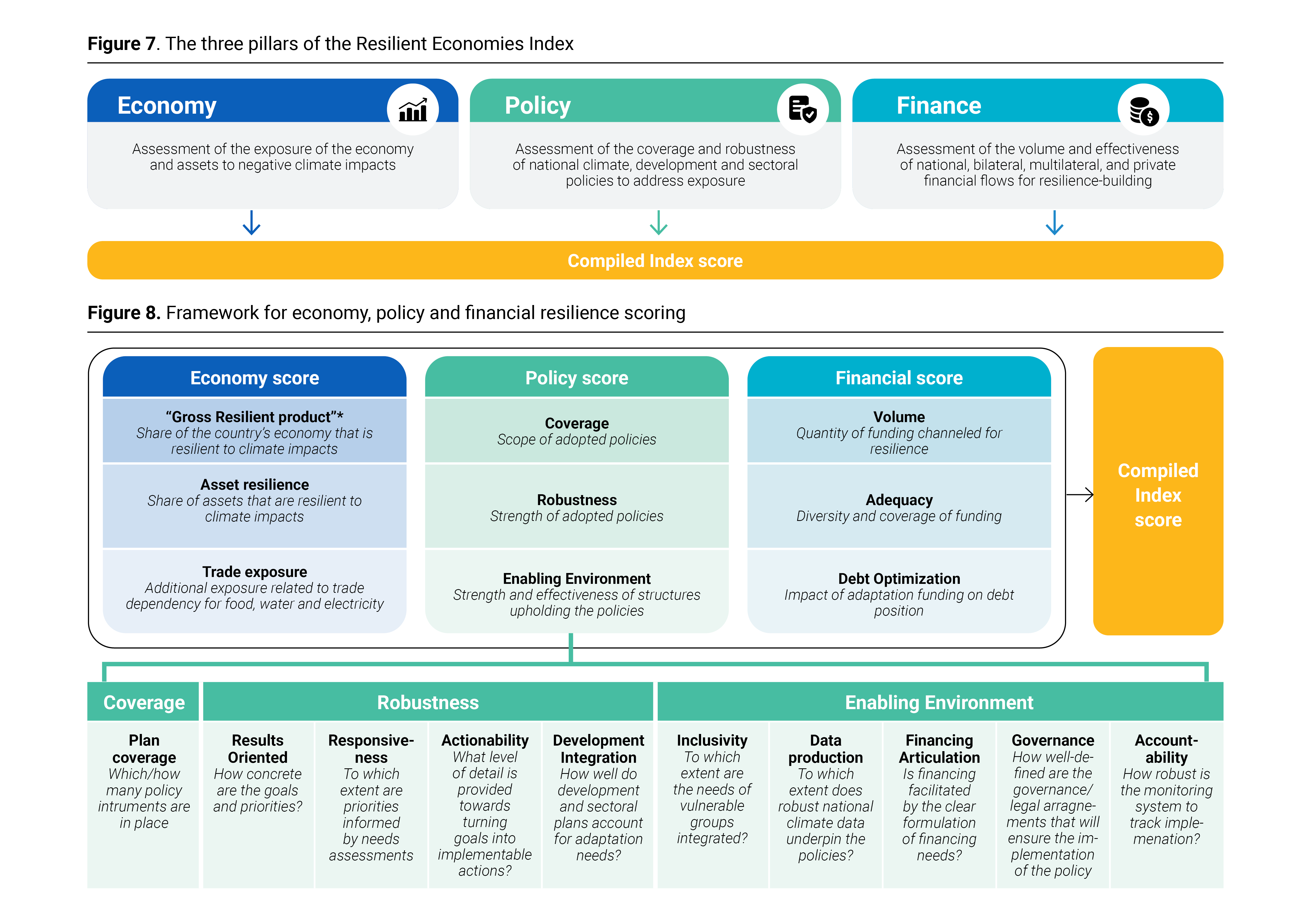

The Index

The Resilient Economies Index assesses how African countries are exposed to and prepared for climate risks. It covers three pillars: economic exposure, policy planning, and access to finance to turn plans into action. Countries are grouped into five two-tier categories—Pioneering (Upper/Lower), Robust (Upper/Lower), Consolidating (Upper/Lower), Emerging (Upper/Lower), and Foundational (Upper/Lower)—to reflect different stages of adaptation progress. The Index is designed to help governments, development partners, investors, and other economic actors pinpoint where progress is occurring and where further effort is needed to strengthen resilience.

The current edition covers 54 African countries.

Key messages

Africa is identified by the IPCC as the world’s most vulnerable continent to climate change (IPCC, 2022).

The research and analysis behind this report assessed climate adaptation in Africa, examining economic exposure, policy, and finance.

Findings show that:

- Rapid policy progress, but a financing gap.

Many countries have robust frameworks—particularly around inclusion of vulnerable groups and clear priority-setting—yet mobilization of finance lags due to debt burdens, limited volumes of funding, and underutilized private-sector capital. - Stronger action amid higher risk; complacency risk at higher incomes.

Lower-income nations advanced adaptation despite greater exposure, while wealthier countries showed slower translation of capacity into measurable resilience outcomes. - High exposure of economies and assets, yet resilience is highlighted.

Economic activity is especially at risk in lower-income countries, while physical infrastructure faces greater exposure in higher-income ones. Only 10 countries have less than 10% loss exposure to GDP or infrastructure assets (2025-2050).

At the same time, around 90% (average of 87.1%) of all economic activity of African economies is already positioned as resilient to climate risks (over the same 2025-2050 time period). The best performing economies have, in fact, already minimized GDP exposure to approximately 5% of GDP, or a GRP of 95%, highlighting the real potential for improvement available for de-risking African economies from climate threats. - Infrastructure growth and trade dependencies heighten vulnerability.

Rapid infrastructure expansion, overreliance on trade—particularly food imports—and concentrated economic exposure underscore the need to fully integrate adaptation into all aspects of development planning. - Scaling finance is critical to closing the adaptation gap.

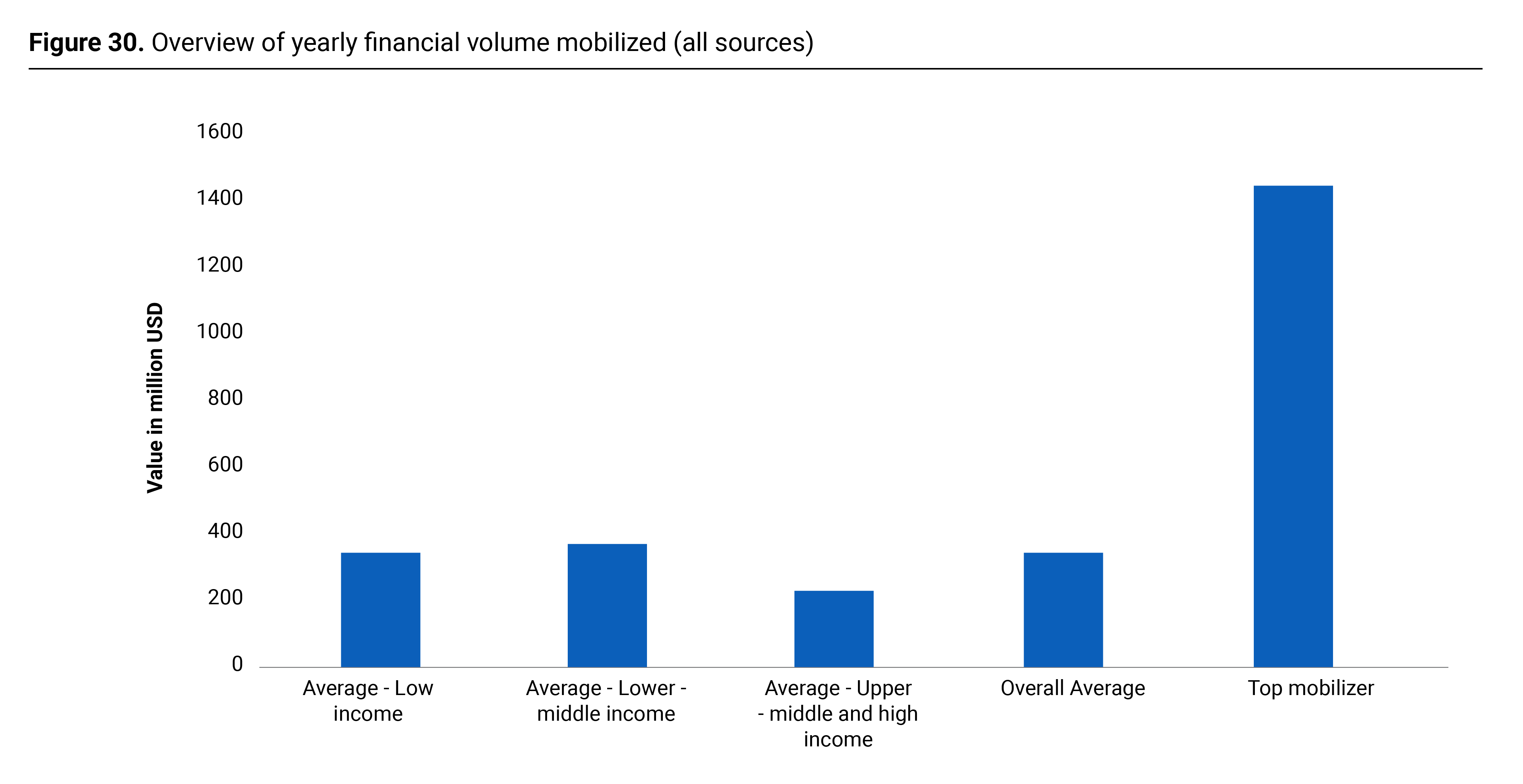

Expanding finance through debt relief, innovative financial mechanisms, and greater private-sector engagement is essential to accelerate resilience-building across the continent. All African economies would need to be mobilizing financial resources for resilience at the same rate as the continent’s top performer, at US$1.45 billion/year, for resources to match actual needs, when the current average mobilization of all (domestic, public, private, international) adaptation finance for all Africa is approximately US$340 million/year. - Policy strength attracts support, but gaps persist—even for pioneers.

Countries with robust policies tend to draw more assistance, yet substantial work remains even among those in the pioneering tier. - Debt constraints and disaster-driven learning shape outcomes.

A “debt wall” limits financing—62% of adaptation finance in Africa is debt—restricting fiscal space for many economies in distress. Countries including those at high-risk of debt distress have been found to mobilise up to 90% of their adaptation funding in the form of debt. Experience with climate disasters correlates with stronger Index performance, underscoring the need for knowledge sharing and proactive action across the continent.

Index score

Key message 1

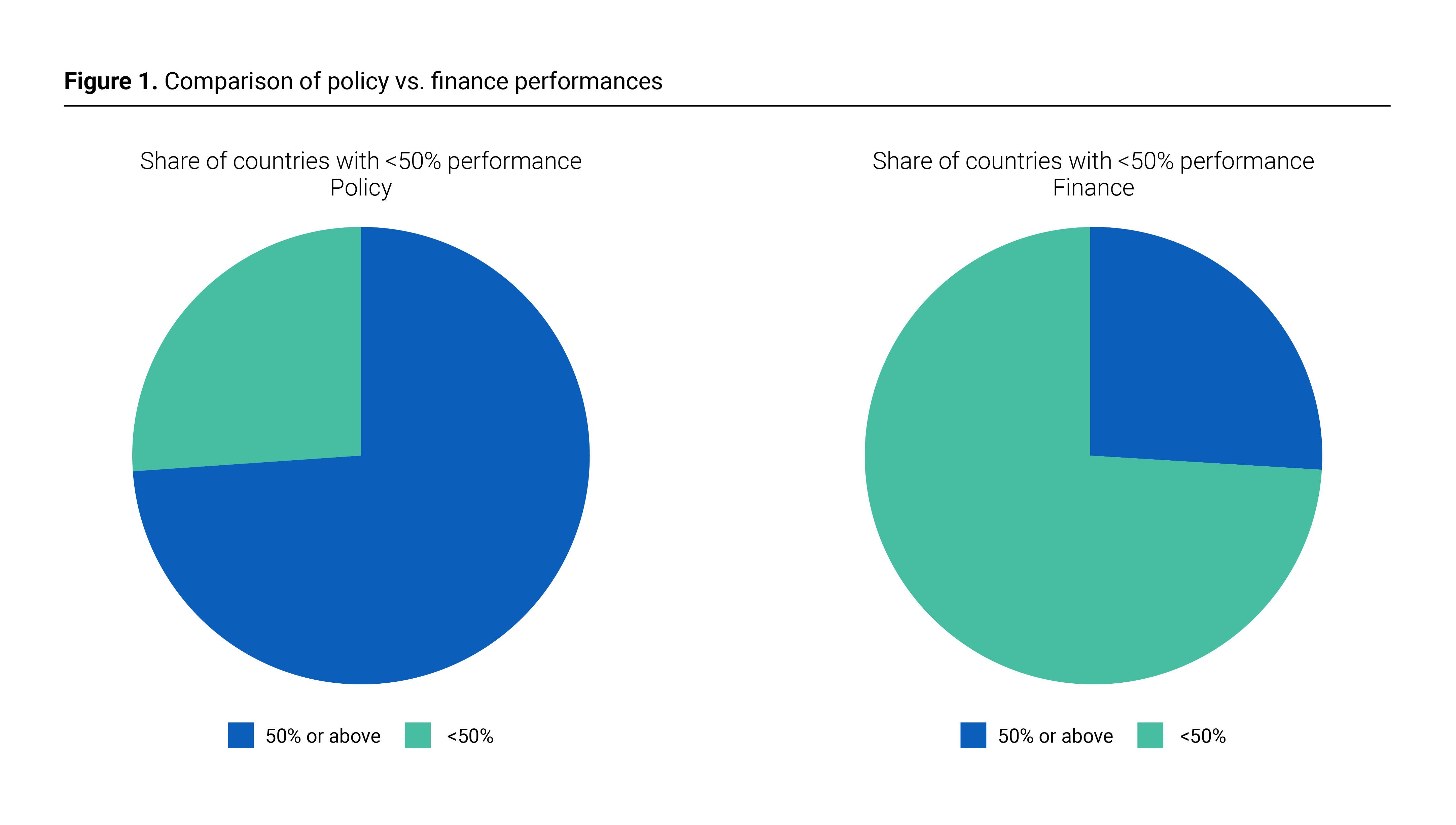

Policy progress outpaces finance, widening the ambition–action gap.

Forty countries score at least 50% on the policy pillar, yet only 14 reach that threshold on finance—leaving strong plans underfunded. High debt burdens constrain fiscal space even for top policy performers. Closing this gap requires stronger financial mechanisms, targeted debt relief and restructuring, and scaled resource mobilization so policies translate into implementation and resilient growth.

Key message 2

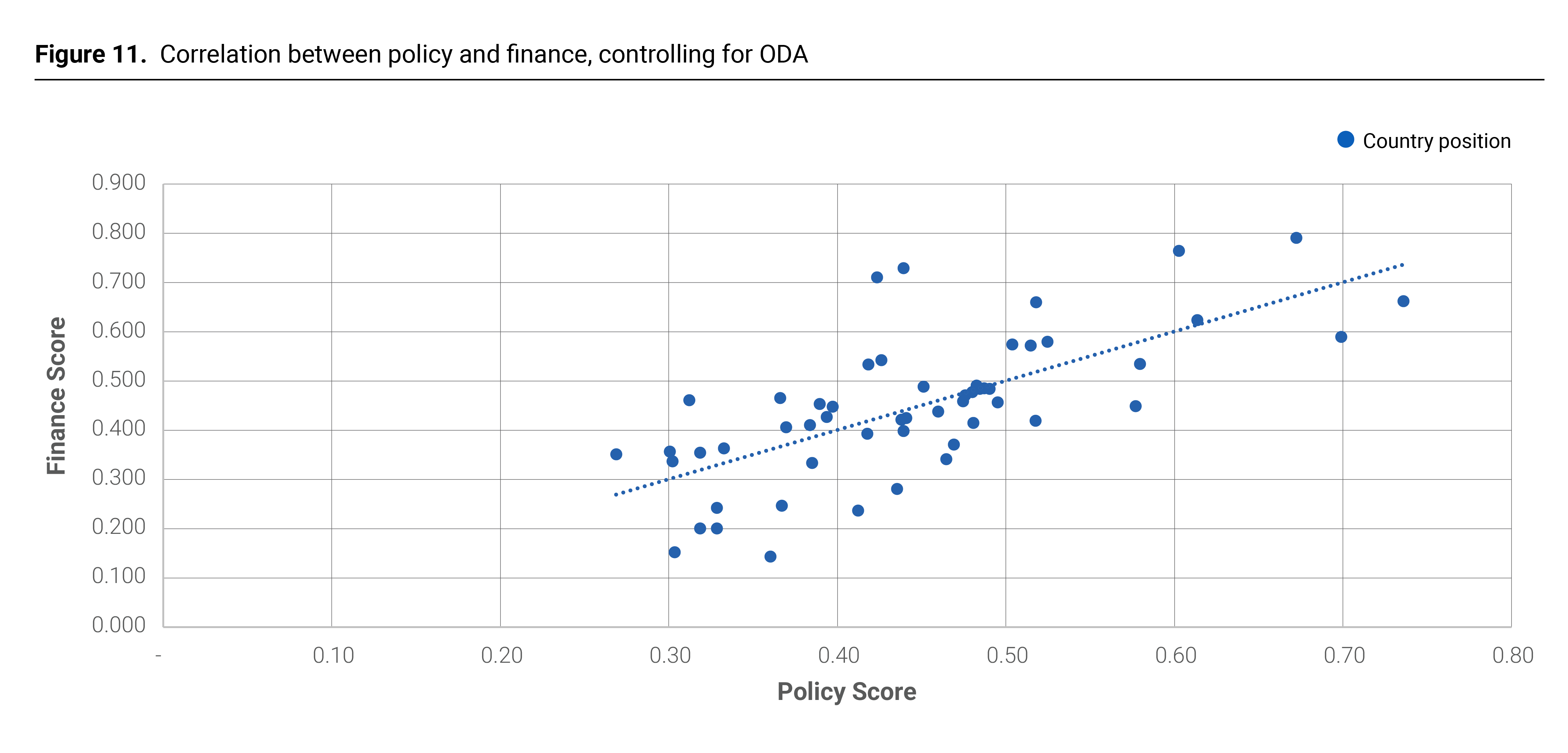

Robust policy frameworks catalyze finance—especially where ODA is limited.

Countries with strong, well-articulated adaptation plans tend to perform better on financial mobilization indicators when controlling for ODA, with plan coverage the strongest predictor of funding outcomes. Mainstreaming adaptation across national policy frameworks clarifies needs and priorities, guiding capital toward implementation. In contexts with low ODA inflows, policy strength plays an even greater role in steering finance. Governments should keep prioritizing policy development, while partners help ensure that countries with less external support do not fall behind on adaptation finance.

Key message 3

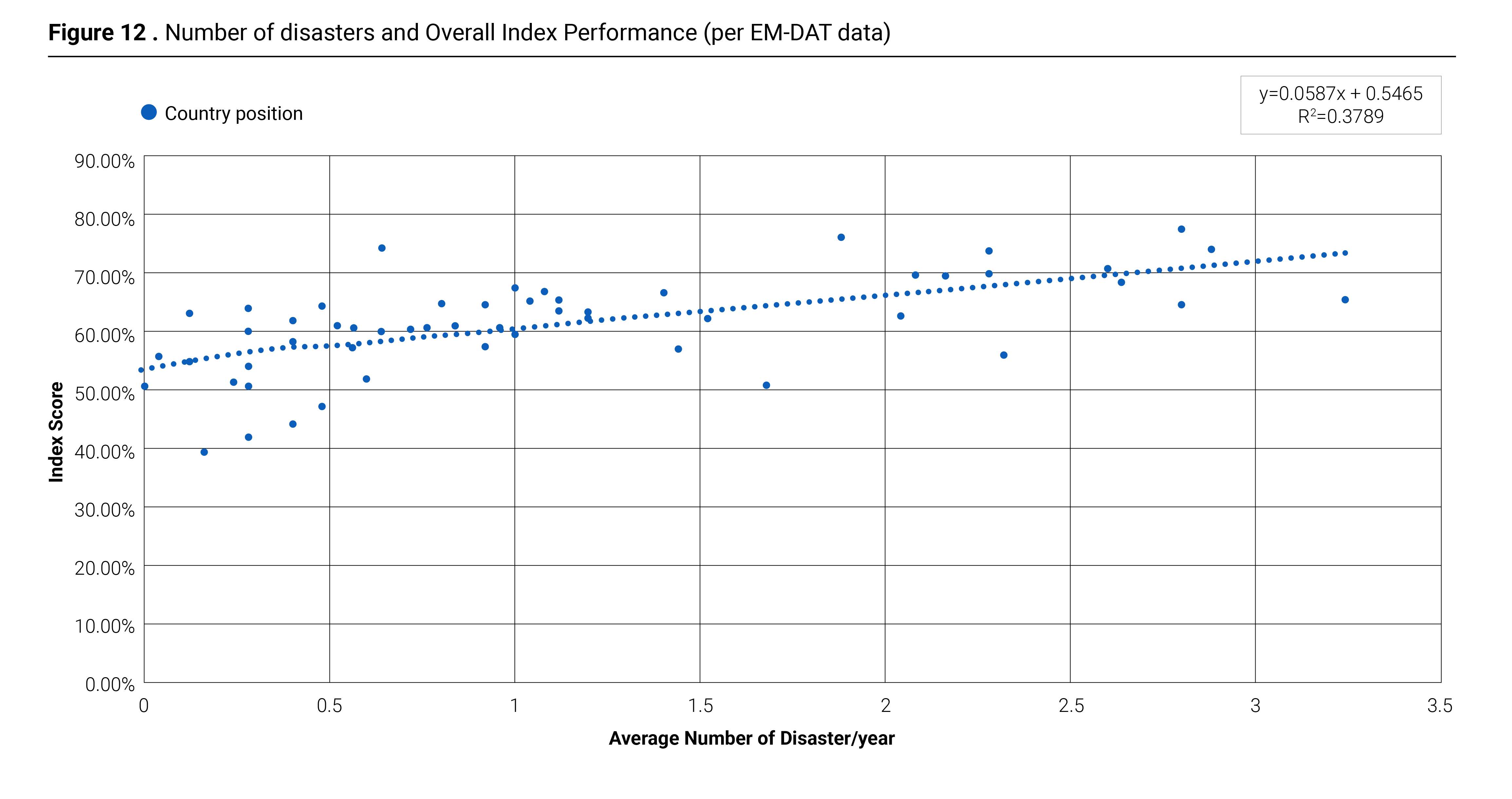

Disaster experience correlates with stronger preparedness.

Countries facing frequent climate disasters over the past 25 years (EM-DAT; see Figure 121) tend to show stronger leadership in adaptation policy and finance, as repeated shocks build urgency, political will, and institutional capacity. But lower-exposure countries shouldn’t wait—advancing policy and financing now cuts future losses and shifts adaptation from reactive to proactive.

Key message 4

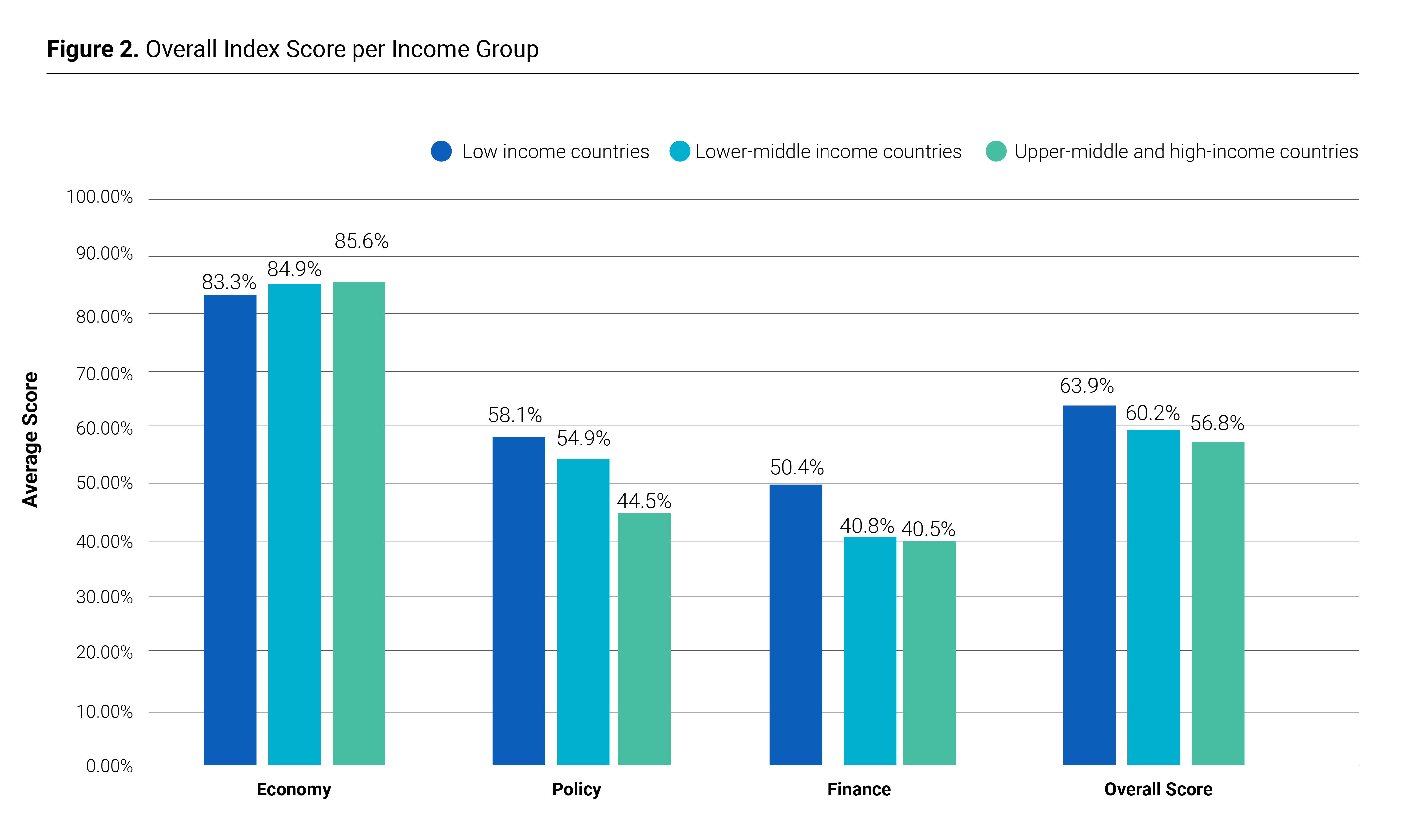

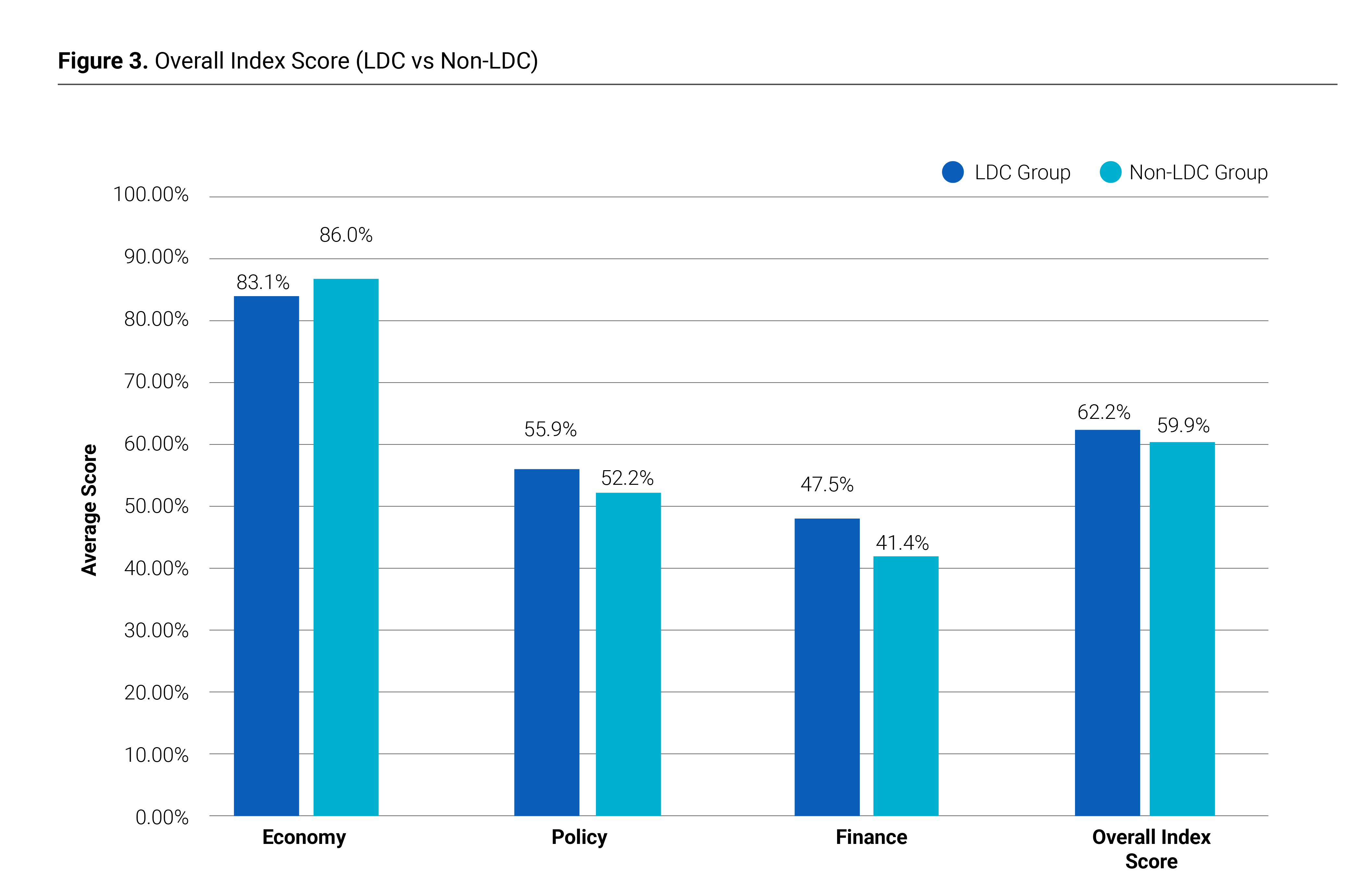

Higher exposure, relative stronger preparedness at lower incomes.

Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and low-income countries face high economic risks yet demonstrate stronger policies and financing for adaptation than other income groups: the LDC average economic score in the Index evaluation is 83.1% (86% for non-LDC), the average policy score is 55.9% (52.2% for non-LDC), and the average finance score is 47.5% (41.4% for non-LDC).

By contrast, upper-middle- and high-income countries, despite robust economic resilience, face challenges in demonstrating similar trends for policy and financial actions. Therefore, this highlights that those most vulnerable act faster, while those with fewer challenges risk falling behind in climate preparedness—underscoring the need for increased international support and debt relief for LDCs, alongside stronger policies and increasing finance mobilization from wealthier nations.

Economy

Key message 5

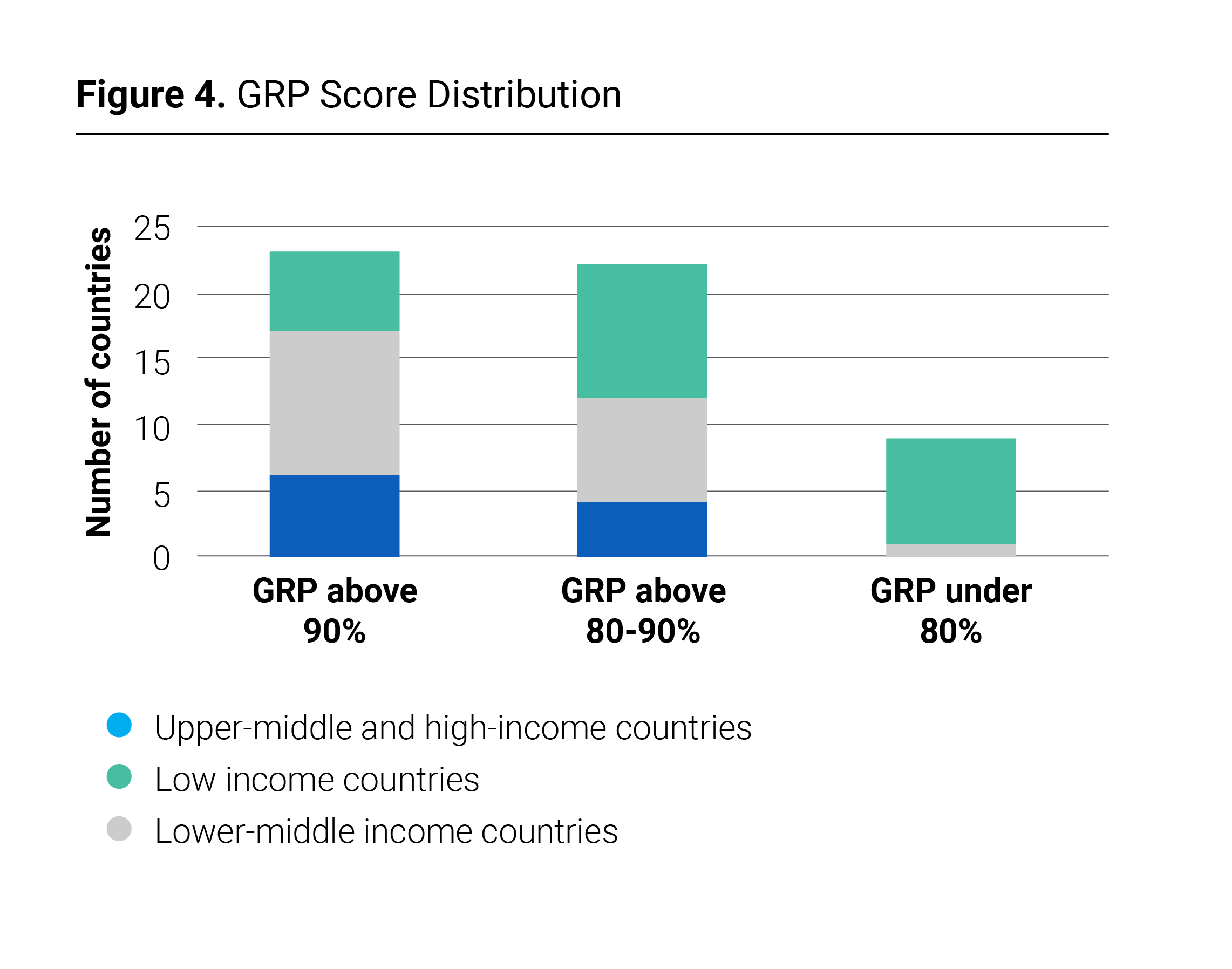

Resilient growth is achievable, but exposure threatens prosperity.

Gross Resilience Product (GRP) analysis shows that the majority – 31 – African economies face substantial losses at or in excess of 10% of GDP between now and 2050. At the same time, around 90% (average of 87.1%) of all economic activity of African economies is already positioned as resilient to climate risks (over the same 2025-2050 time period).

ʼResilience generally improves with income—upper-middle and high-income countries perform better—yet unchecked exposure will dampen medium- to long-term growth and trigger cascading socio-economic effects. Diversification of economic activities and workforce concentration from the high-risk agricultural sector supports higher levels of resilience, as do measures that enhance the resilience and productivity of agriculture.

The takeaway: invest in resilience now to limit future damages and safeguard sustainable development.

Key message 6

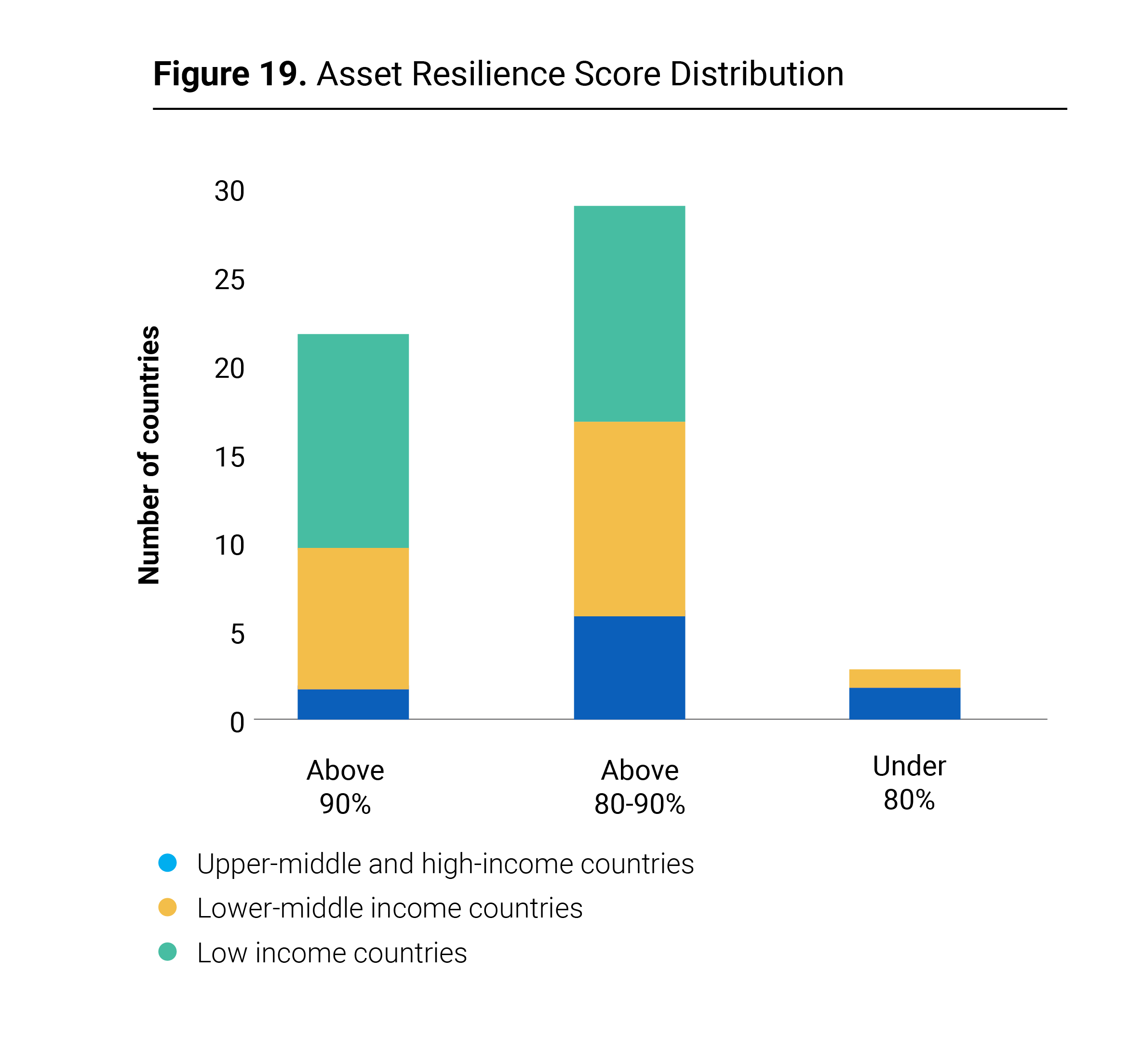

Africa’s infrastructure boom must be climate-smart.

Thirty-two countries have over 10% loss exposure of physical assets, with upper-middle and high-income countries faring worse on resilience indicators—partly due to higher infrastructure density.

Priority actions: embed adaptation into planning, standards, and financing for all new (and retrofitted) infrastructure so the next wave of development is resilient and sustainable.

Key message 7

Optimize trade for reduced climate risks.

Country-specific risks in food, water, and energy trade mean over-reliance on climate-affected imports can transmit external shocks. An optimal window of trade should be targeted.

Aim for a balanced portfolio: strengthen domestic supply where feasible, diversify import sources and routes, build regional value chains, and use risk- management tools (buffers, hedging, strategic reserves) to capture trade’s benefits while minimizing climate-driven volatility.

Policy

Key message 8

Mainstream adaptation across development planning — move from intent to implementation.

Integrating actionable climate adaptation priorities into national and subnational development and sectoral plans is crucial for translating international commitments into concrete actions that cut across levels of government and sectors. However, adaptation remains insufficiently embedded in development strategies, as the integration of adaptation into national development and sectoral plans remains the most critical policy improvement.

Evidence suggests that, on average, analyzed plans that acknowledge adaptation with broad objectives score higher (78%) in comparison to indicators measuring the articulation of goals into key projects and programs, the provision of clear timeframes, and concrete roles in a way that facilitates financing, which do not exceed a 32% performance on average.

Key message 9

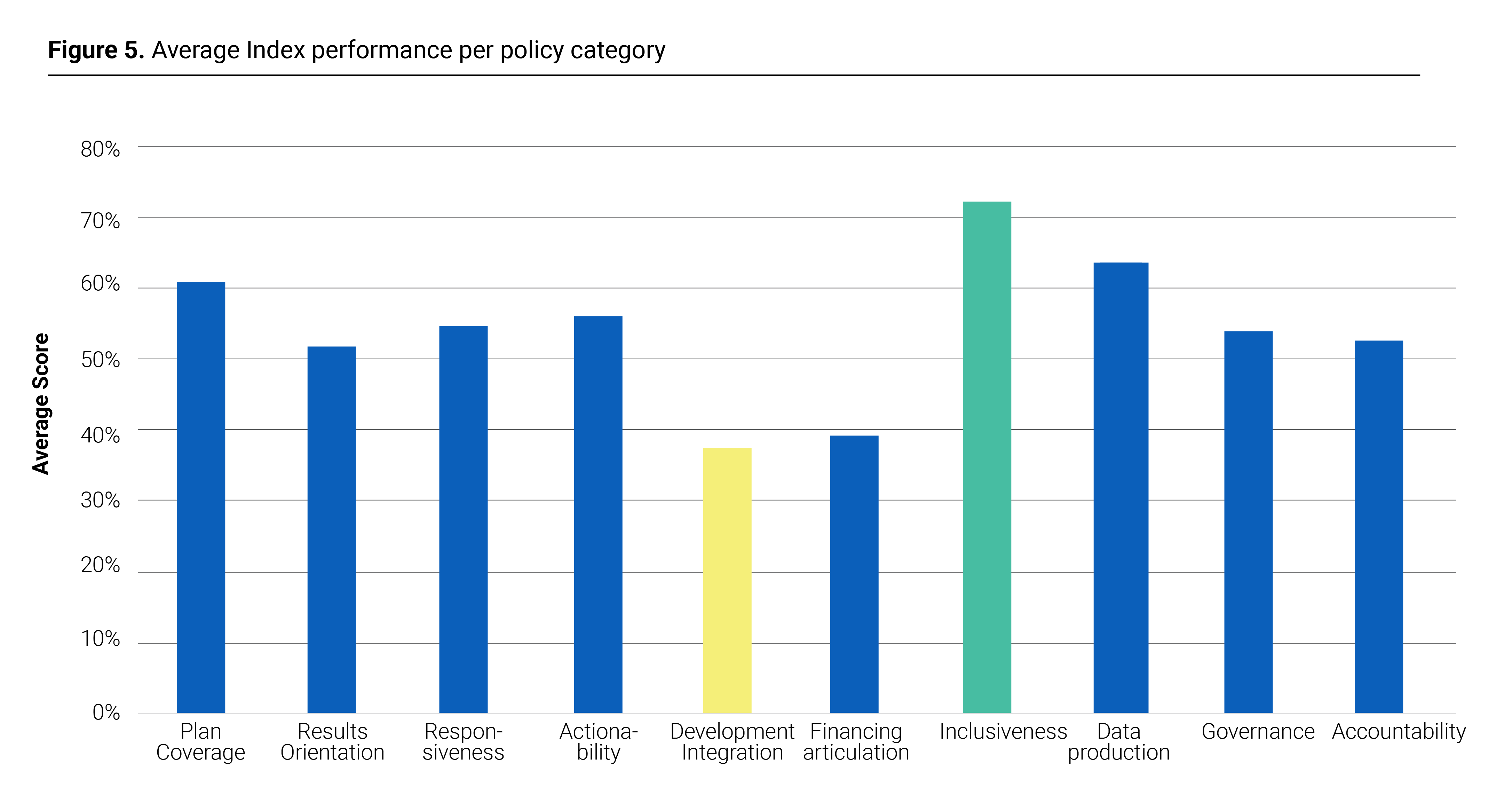

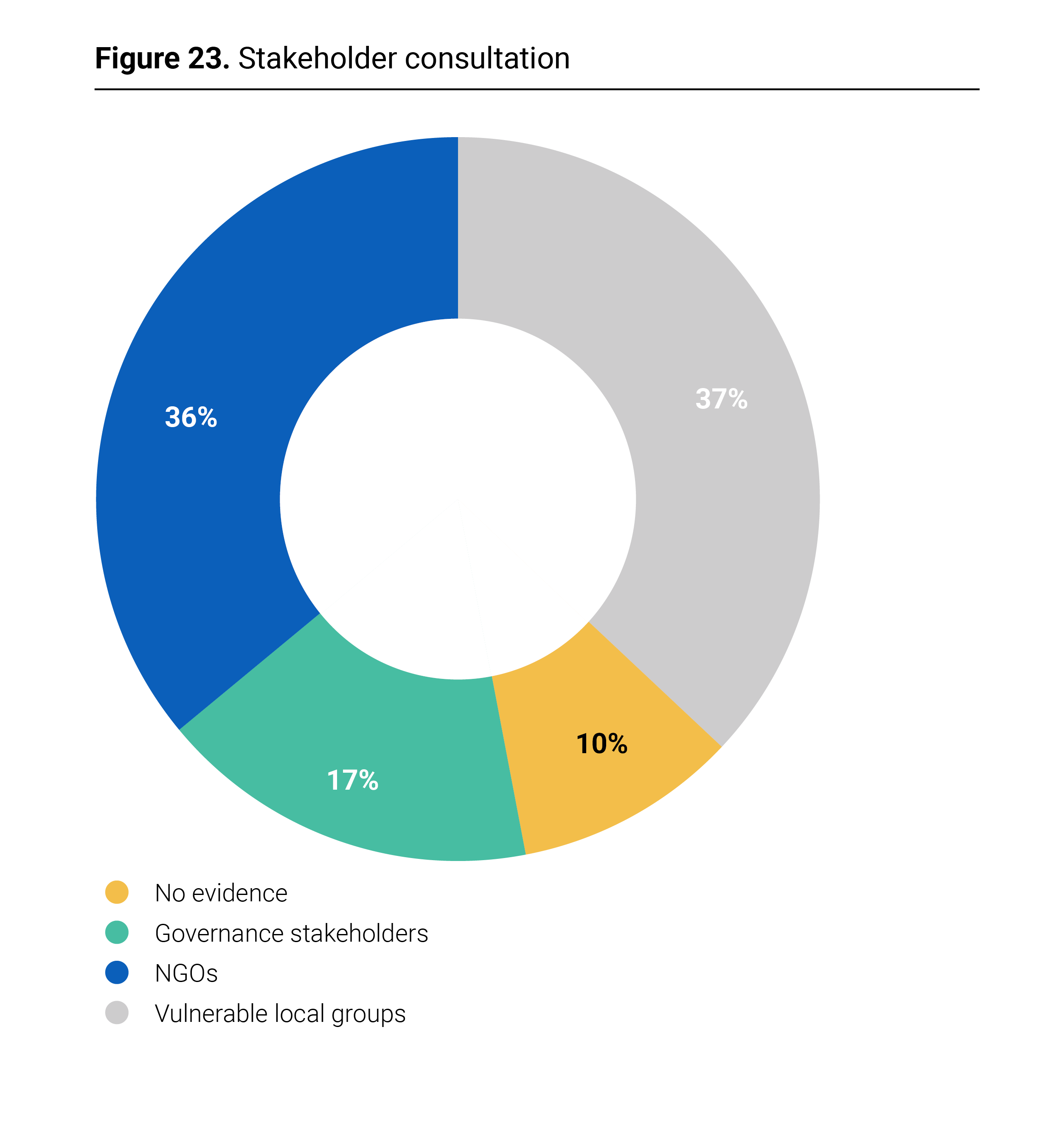

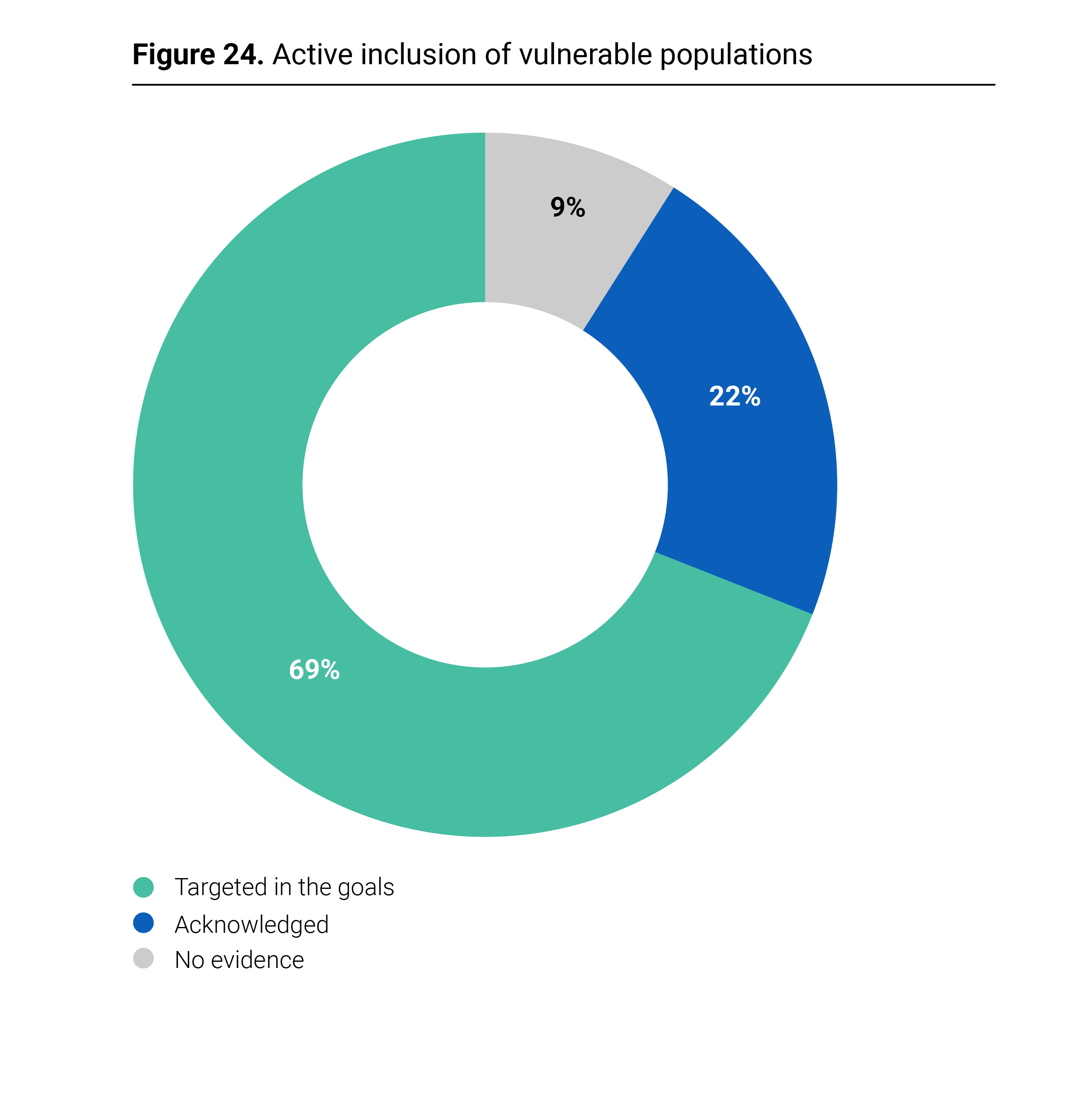

Inclusiveness is a core strength of Africa’s adaptation policy.

The Index shows inclusiveness as the highest-scoring thematic cluster (average score: 72.4%). Many countries systematically engage NGOs, vulnerable groups, and local actors in plan design, and embed actions that directly target these communities.

This community-rooted approach sets a strong baseline for progress—now the priority is to match it with financing for locally led adaptation and robust feedback and accountability mechanisms.

Key message 10

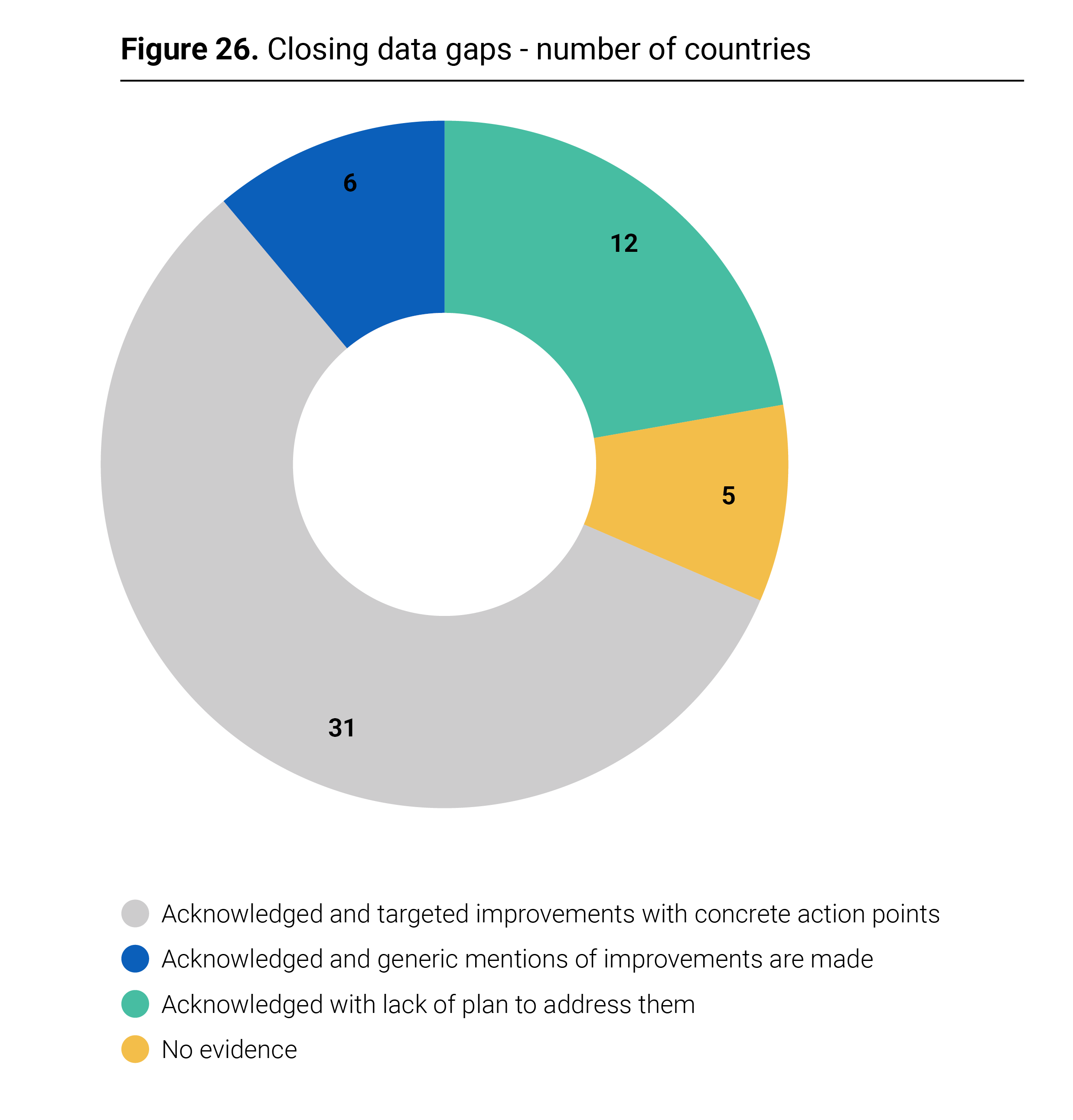

Encouraging signal for more robust climate data despite existing gaps.

Robust national systems—linked to regional networks—are essential for evidence-based adaptation. Over half of African countries acknowledge shortfalls in infrastructure, capacity, and regional integration and have outlined steps to address them.

As such, countries should continue to strengthen national climate observation systems by expanding coverage, modernizing infrastructure, enhancing regional integration, increasing investments, and building institutional capacity.

Key message 11

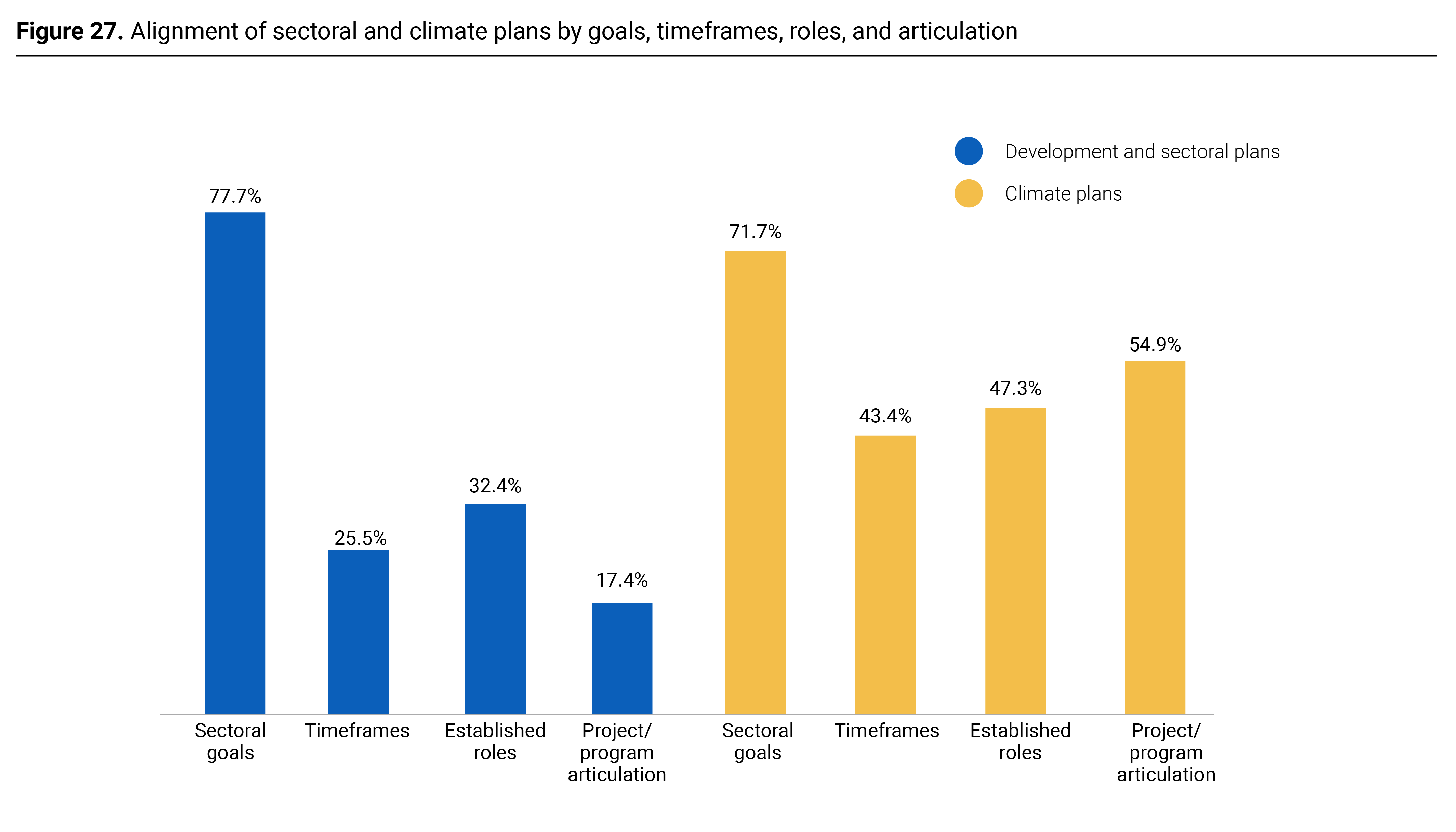

Move from aspirations to bankable, time-bound delivery.

There is a pressing need to move from broad adaptation goals to actionable objectives. While African climate, development, and sectoral plans perform on average strongly in setting overarching goals (71.7% and 77.7% respectively), they fall short in translating these ambitions into concrete measures.

Many plans lack clear timeframes, defined institutional responsibilities, and well-articulated projects, resulting in average performance barely exceeding 50%.

This gap constrains effective implementation, progress tracking, financing, and accountability. Embedding these measures into policy and planning frameworks moves climate objectives beyond normative statements and enables more effective coordination, investment, and monitoring.

Finance

Key message 12

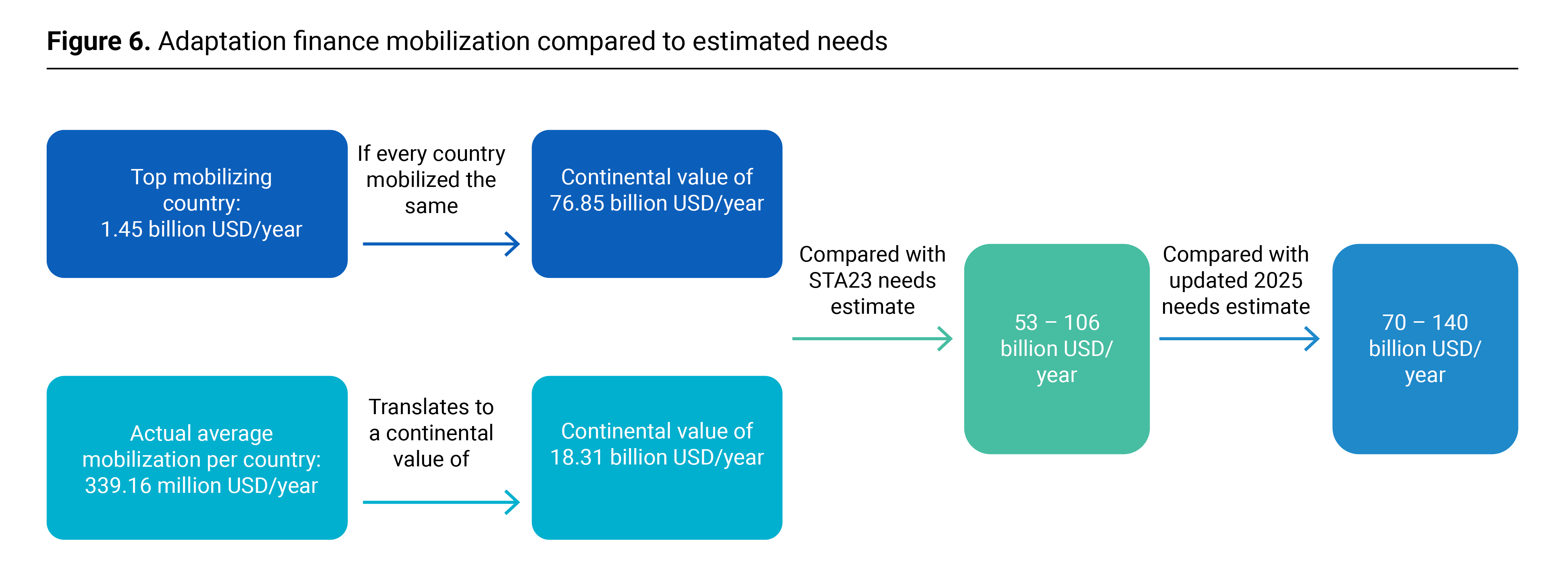

Financial mobilization must scale dramatically.

To meet Africa’s adaptation needs, every country would have to mobilize finance at the pace of the continent’s top performer (1.45 billion USD/year). At current trends (continental average of 340 million USD/year), only ~25–33% of the minimum funding need will be met by 2030.

Even the highest performing finance mobilizer among

all African economies is estimated to fall short in its mobilization efforts by between 30% and as much as 230% (depending on the need evaluation referenced). A core issue is countries are under-specifying requirements—only about one-third have needs estimates that match the scale of the challenge, and even leading mobilizers underestimate their gaps.

Priorities include rigorously quantifying needs, embed costed pipelines in NDCs/NAPs and sector plans, expand concessional flows and guarantees, pursue targeted debt solutions, and crowd in private capital to close the

adaptation finance gap.

Key message 13

Build resilience without hitting a debt wall.

The debt wall refers to a situation where finance options become restricted when finance is mainly available in the form of debt and countries are in or approaching debt distress. Over-reliance on borrowing is eroding fiscal space—62% of adaptation finance in the Index is debt—including in countries already in distress, with even “moderate risk” nations vulnerable if they lean heavily on loans.

Countries including those at high-risk of debt distress have been found to mobilise up to 90% of their adaptation funding in the form of debt.

Countries and partners should prioritize debt-compatible solutions such as more grants and highly concessional finance, guarantees and blended structures to de-risk private capital, debt-for-climate swaps, catastrophe and resilience bonds, and SDR rechanneling—so resilience rises without undermining debt sustainability, especially given Africa’s minimal contribution to global emissions.

Key message 14

Private capital is largely untapped for adaptation.

While the analysis identified differences in the ability to attract private finance, the most striking element that emerged is that private contributions to adaptation finance are critically underexploited, with an average of just 3.7% of private sector financing for adaptation projects.

Only 11 countries have private sector finance representing more than 5% of their total funding portfolio. Even among the seven countries that have relatively higher private sector finance mobilisation ability, private sector funding remains largely underexploited (at an average of just 11% of overall project finance).

For instance, CPI (2022) data from other regions, such as South and East Asia, show examples of private sector mobilization, with significant scope for commercial financiers and enterprises to develop and fund adaptation solutions, products, and services.