Improving Climate Risk Insurance in Small Island Developing States

Climate risk insurance is a financial mechanism designed to provide protection against the economic losses associated with climate-related events, such as extreme weather conditions, natural disasters, and gradual environmental changes driven by climate change. In light of the rising frequency and intensity of climate-related disasters, it is apparent that most Small Island Developing States, which are located on the frontlines of climate change, suffer from what is called a protection gap: the difference between the insurance cover that is needed and the amount of insurance that is actually purchased.

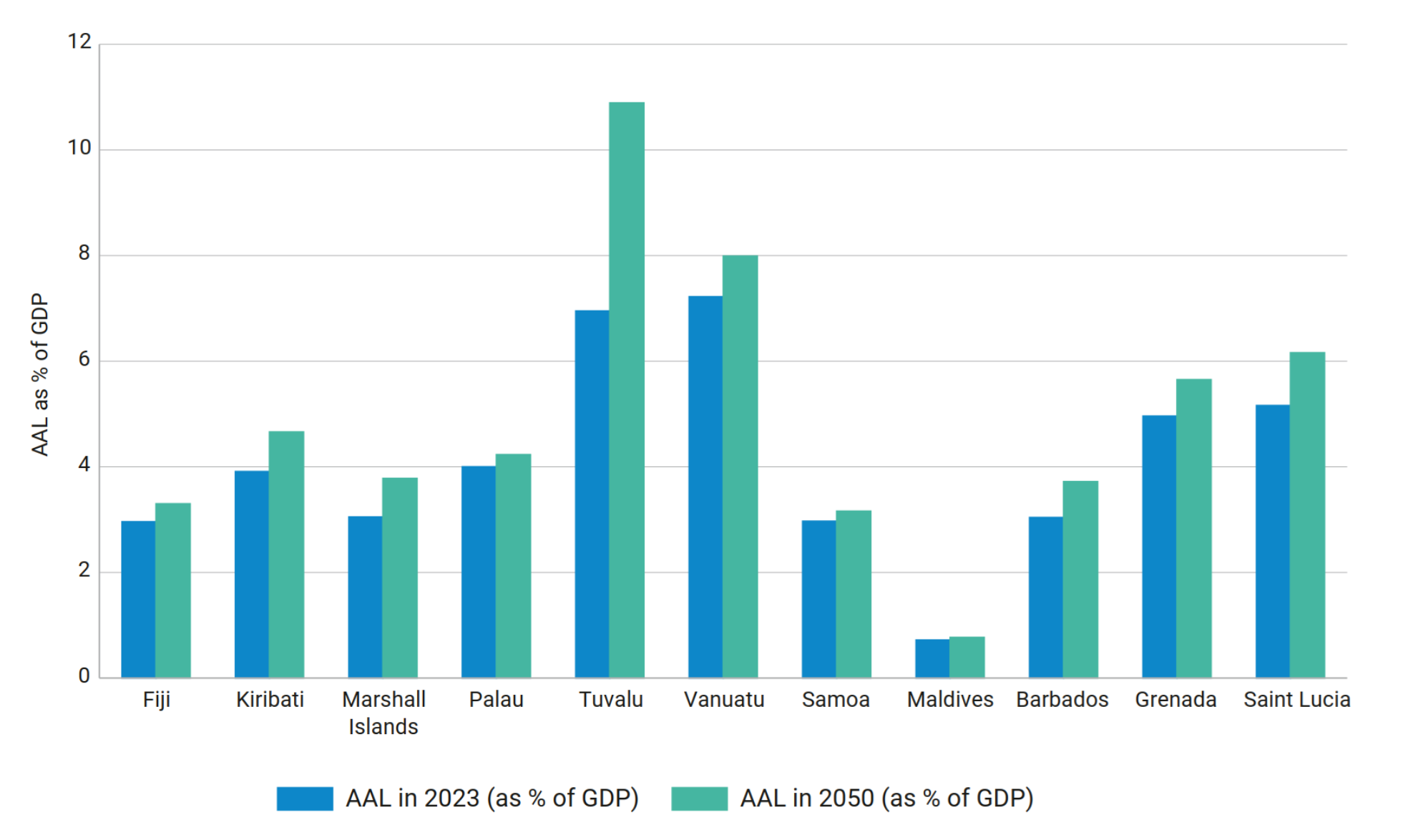

How can this gap be quantified? The risk capital markets use a well-established modeling approach to risks, called the catastrophe (CAT) risk modeling, to analyze levels of hazard probablity, exposure, and vulnerability under varying levels of threat of the area under study. For example, a 2023 analysis by the University of Cambridge’s Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL) of six climate perils (including tropical cyclones, storm surges, floods, and drought) with exposure and vulnerability across 11 SIDS found that these countries now face losing between 50% and over 100% of their GDP from climate-related disasters. The CISL study also shows these losses are set to grow 10 to 15% by mid-century. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Total Average Annual Loss per Country for 2023 vs 2050 as % of GDP

Source: CISL 2023

These levels of financial risk are not matched by the amount of protection currently in place. On average, less than 5% of the population (individuals and households), representing around 1 to 2% of GDP, enjoy financial protection against the consequences of climate shocks. At the sovereign level, the average coverage ranges between 1% and 5% of GDP.

Different types of climate risk insurance (regional risk pools, catastrophe bonds, blended insurance, and microinsurance, among others) provide a layered and diversified approach to managing the financial impacts of climate change in SIDS, addressing both sovereign and individual needs across different sectors and levels of society. Despite their success over a period of time, there is a pressing need to scale up these vital programs across SIDS. The biggest limiting factor in bridging the protection gap is that SIDS lack the financial resources and fiscal capacity to afford the insurance premiums that would provide more significant levels of coverage.

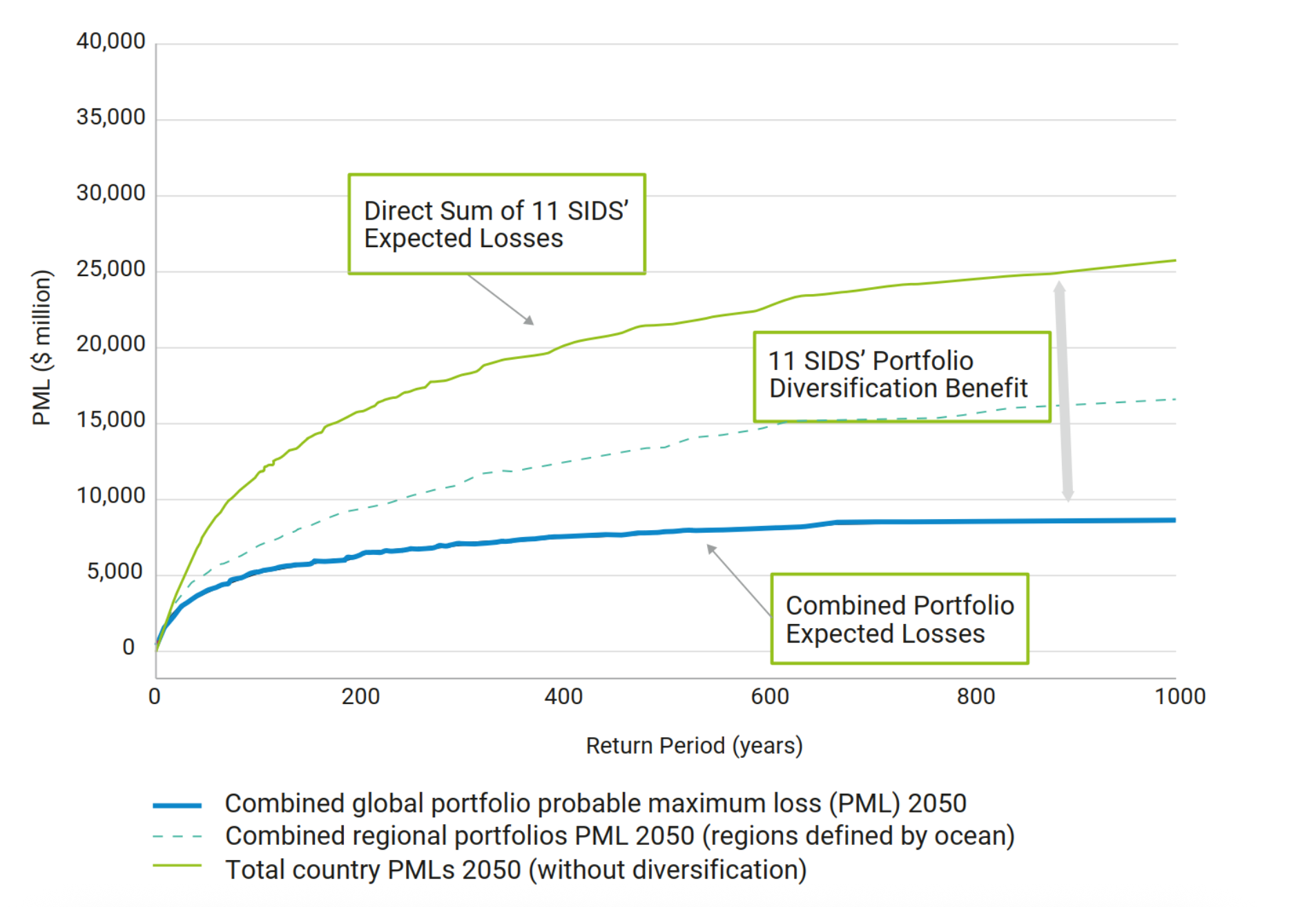

How can this problem be addressed? The core principle of insurance is sustainable risk sharing, which underpins its key features of security and affordability. Therefore, diversification is critical to generating further capacity per premium dollars in risk pools. Figure 2 shows the results from the CISL study looking at the diversification benefits of the 11 SIDS across the five perils. At the return periods analyzed, the diversification benefit could be as much as 30 percent less than the pure risk price for each country alone.

Figure 2: Diversification Benefits of Regional and Global Risk Pooling

Source: CISL 2023

The CISL study modeled the pure premium required to protect the economies of the 11 SIDS, modeled from losses exceeding an equivalent of 10 percent of GDP. The modeling calculates the total uninsured annual Probable Maximum Loss (PML) for each of the 11 countries at 0.1 percent annual probability (or a 1-in-1000-year event). The total amount is about $25 billion. A joint umbrella insurance mechanism for all 11 countries for this level of protection would require $314 million per year.

The CISL study shows, then, that climate risk insurance should be a key component of international adaptation finance. In fact, effective climate risk insurance systems encourage members to implement adaptation measures (such as drought-resistant crops or flood defences), so that risk is reduced and insurance is affordable.

Based on the analysis provided by the CISL study and the policy considerations described in this chapter, a potential roadmap to leverage insurance as a tool for climate adaptation in SIDS would have the following two elements:

a) Build an umbrella stop-loss for extreme events (through a mosaic of risk transfer programs) so that losses in these highly exposed countries are protected above a defined level of GDP. Each of the risk transfer programs can cover specific sectors (e.g., agriculture and fisheries, critical infrastructure, housing) in defined areas and communities or at national scale.

b) Cover smaller, higher-frequency losses through appropriate mechanisms, creating a complementary mosaic of programs alongside those for extreme events.

The roadmap would include four key steps:

1. Evaluating climate risks using methods and metrics of the risk capital markets;

2. Undertaking a climate adaptation strategy, prioritization and programming;

3. Building climate risk insurance and financial derisking systems; and

4. Achieving maximum benefit from adaptation and climate risk insurance.

The four-step approach should be anchored to the National Adaptation Plans of SIDS, to enable greater coordination within countries and between countries at regional and international levels. In turn, it can strengthen the NAPs by bringing in further significant stakeholders, including economic departments, financial regulators, banks, investors, insurers, and business organizations.

Another key stakeholder in this process are the regional risk pools such as African Risk Capacity (ARC), Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility Segregated Portfolio Company (CCRIF, the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Insurance Company (PCRIC), and Southeast Asia Disaster Risk Insurance Facility (SEADRIF), which are increasingly important in enhancing disaster resilience and adaptation within their regions.

Last, a major breakthrough will be to ensure that SIDS are proportionally incentivized and rewarded for implementing adaptation and climate risk insurance interventions. Without this, there is limited immediate economic motivation for improving physical and financial resilience. For example, it is crucial that improved financial protection is recognised as a contingent capital asset and reflected in improved costs of sovereign debt, knowing that the country has the financial resources to recover after disaster.

Written by Chandrahas Choudhury based on chapter ‘Insurance’ by Ana Gonzalez Pelaez (Howden Group)

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.