Solutions for Vanishing Coastlines: Adapting to Coastal Erosion in Small Island Developing States

This article was originally published on PreventionWeb on November 20, 2024.

It is republished here by the Global Center on Adaptation under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO License.

A minor change was made to update the publication date of the referenced report.

The 2025 edition of the Global Center on Adaptation (GCA)’s State and Trends in Adaptation report (STA25) provides an integrated overview of climate risks, adaptation action, and financing needs and gaps in Small Island Developing States (SIDS). The report, published in October 2025, includes a chapter on coastal erosion, with key points below.

Coastal erosion threatens vulnerable coastal communities across SIDS. In response, island nations must rapidly deploy effective and scalable adaptation solutions that utilize nature, community participation, and innovative technologies.

Understanding Coastal Erosion in SIDS

Coastal areas in SIDS underpin critical industries such as tourism and fisheries, provide protection against coastal hazards, harbour productive and diverse ecosystems, and are integral to the social fabric of local communities. However, due to the concentration of economic and community activities within coastal zones, SIDS have been identified as some of the most vulnerable countries to climate change and coastal erosion.

Alongside the increasing impacts of climate change and rising sea levels, various anthropogenic activities are exacerbating coastal erosion processes in island nations. Poorly regulated coastal development, land use changes, sand mining, and the degradation of coastal ecosystems all contribute to the acceleration of coastal erosion in SIDS.

Using satellite data from 1984 to 2015, one study of global erosion trends estimated that the loss of permanent land in the world’s coastal zone was 31 m over that time, or 1 m/year. This trend is more severe in areas with substantial relative sea level rise and frequent extreme events, such as SIDS. Across the Caribbean, island nations are expected to lose up to 3,900 km2 of land to rising seas and erosion by 2050, with the total economic value of this projected loss of land estimated between US$406 billion and US$624 billion.

In response to this challenge, urgent action is required to find sustainable and cost-effective solutions that can be implemented at scale to limit the negative impacts of coastal erosion and sea level rise. This requires rapidly deploying public, private, and international finances to fund adaptative and innovative projects across SIDS.

Are current adaptation approaches suitable?

Conventionally, grey infrastructure solutions such as sea walls and revetments have been used to combat coastal erosion and flooding in SIDS, especially in densely populated coastal cities. When properly designed, these structures can effectively stabilize vulnerable coastlines and provide protection to critical assets and exposed communities.

Despite their benefits, grey infrastructure solutions require substantial upfront capital expenditure. Furthermore, they can lead to unforeseen maladaptive consequences that exacerbate erosion processes and cascading impacts that may cause adverse social and environmental effects. In Fiji, two concrete seawalls were constructed to protect remote villages from coastal flooding. However, a post-construction study found that the walls did not alleviate erosion and flooding pressures. Instead, they acted as a dam to the inland drainage system, worsening pluvial and fluvial flooding on the landward side.

In a SIDS context, where sea levels are rapidly rising and other climatic factors are quickly changing, there is a risk that the fixed nature of grey infrastructure can lead to it becoming ineffective and maladaptive. For effective and scalable adaptation pathways, soft solutions must be found that are low-cost, flexible, and able to harmonize with conventional grey infrastructure and create successful coastal protection systems.

What role can nature play in coastal protection?

Nature already plays an essential role in protecting coastlines from erosion. Mangroves, coral reefs, dunes, and ocean grasses all provide protective benefits – from the attenuation of wave and wind energy to the buffering of coastal storm surges. SIDS have some of the highest concentrations of these ecosystems compared to elsewhere.

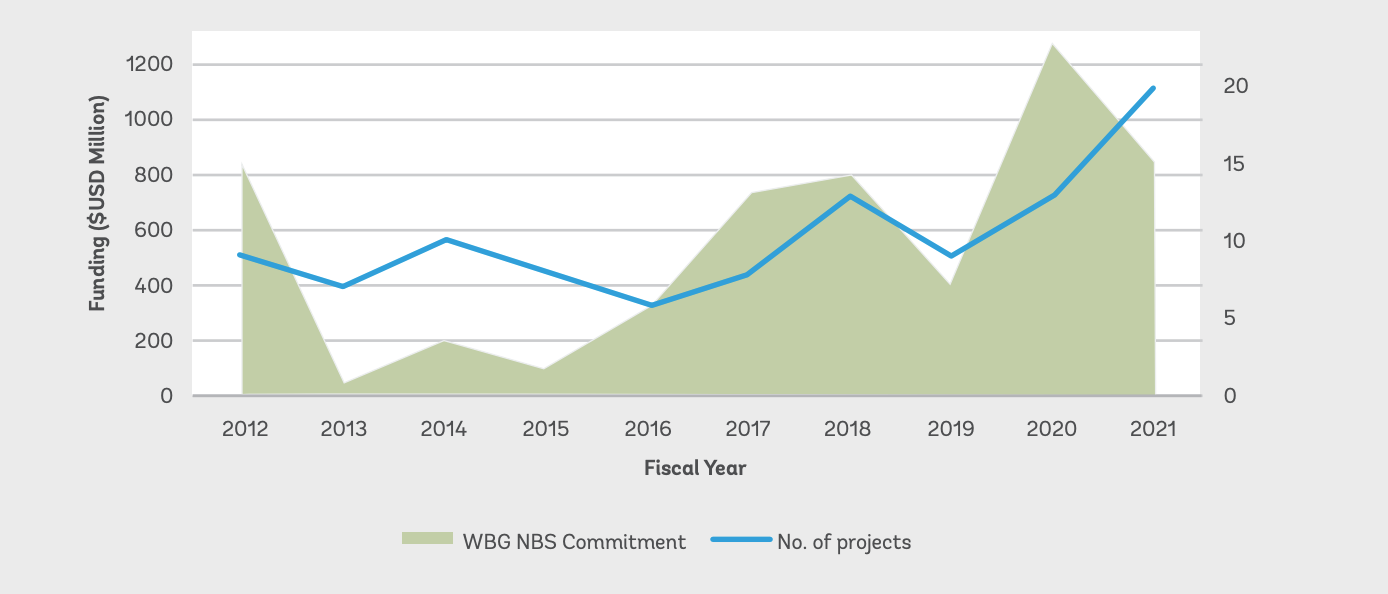

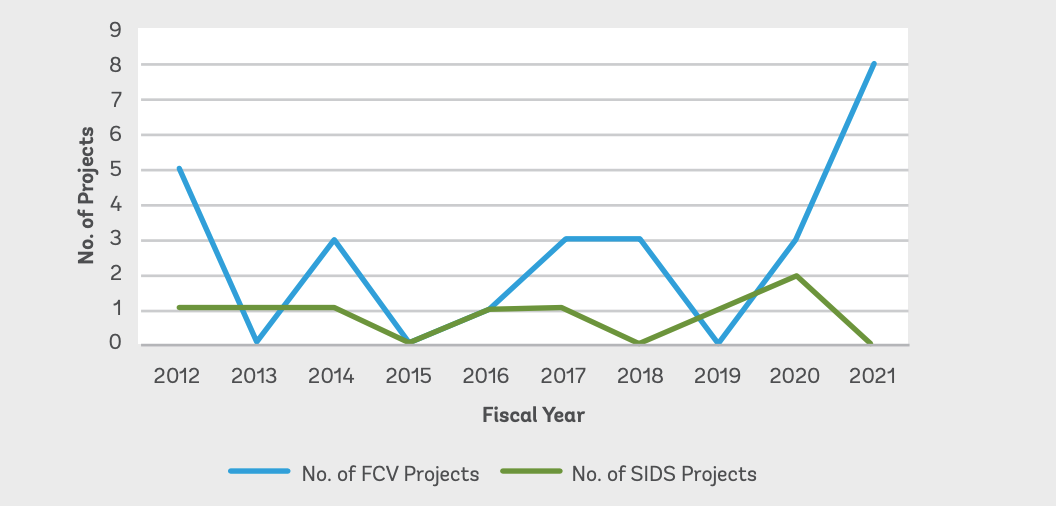

Nature-based Solutions (NbS) are becoming a core component of climate resilience plans. In 2021, the World Bank provided more than US$1 billion of funding for NbS projects globally. However, only eight percent of these projects were implemented in SIDS due to the geographical and access challenges and the severity of climate risks that call for more complex built environment solutions (Figures 1 and 2). The Asian Development Bank allocated US$825 million for coastal ecosystem resilience between 2019 and 2023. This mobilization has increased the number of NbS projects in SIDS, such as dune restoration and coastal vegetation planting.

Figure 1. Approved World Bank Group (WBG) projects with NbS for climate resilience and cumulative approved WBG commitment for NbS from FY12 to FY21

Figure 2. Number of NbS for climate resilience projects in SIDS and FCV (countries affected by fragility, conflict, and violence) context approved by the World Bank from FY12 to FY21 period

Investing in NbS for SIDS, and in particular protecting, conserving, restoring, and sustainably managing the resources within coastal and marine ecosystems, is not just about climate adaptation, mitigation, and resilience. It also helps tackle other challenges highly relevant to SIDS, such as land degradation and desertification, security and access to freshwater, energy, food, and nutrition, as well as protecting biodiversity and nature. Furthermore, targeted climate adaptation investments – with the support of strengthened policy frameworks and skills development programs – could significantly increase NbS jobs in SIDS.

While developing NbS brings protection benefits, it is not a panacea for reducing the advancement of coastal erosion and flooding threats. NbS often requires careful management and long-term investment to achieve the protection benefits and ecosystem services that existing mature ecosystems provide. Therefore, the preservation of already established ecosystems must be prioritized. While ecosystems’ economic costs and benefits are challenging to quantify, evidence suggests their coastal protection value is hugely significant. One study from the World Bank in 2023 found that mangrove forests in Jamaica provide average risk reduction benefits against tropical cyclones of around US$2,500 per hectare per year and US$180 million annually in carbon sequestration benefits. Likewise, the estimated hazard risk reduction benefits of coral reefs in the US are US$1.8 billion annually.

To protect against coastal erosion and flooding, small island nations must take the necessary steps to prevent the degradation of vital coastal ecosystems by banning and monitoring illegal sand mining, preventing the development of assets directly on the shoreline, and halting the clearing of coastal vegetation.

Leveraging community-based adaptation and technology to improve coastal resilience

Many small island populations live in remote locations isolated from main population centres. In these remote communities, adaptation measures that combine community participation with mapping and risk and hazard modelling tools and technologies can better inform protection measures for the most vulnerable communities.

In São Tomé and Príncipe, participatory multi-hazard risk assessments have been conducted in close collaboration with communities in data-scarce environments to analyze adaptation options and increase climate resilience. Elsewhere in the Caribbean, the Resilient Coasts – Caribbean Sea project, running from 2024 to 2026, delivers a series of ‘Living Labs’ or workshops to local communities to explore how they can bolster their resilience by restoring coastal ecosystems and applying NbS. These initiatives provide viable pathways for effective adaptation by combining local knowledge with science to boost resilience to natural hazards.

At the global level, the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) and the World Bank have developed the Nature Based Solutions Opportunity Scan (NBSOS). The NBSOS is a geospatial tool utilizing large global datasets to map the potential benefits of NbS and identify coastal protection investment opportunities worldwide. The tool has been implemented in 20 countries, including in SIDS, to inform coastal protection solutions.

A pathway towards sustainable and scalable adaptation strategies

Small island developing states must take decisive action in the face of rising sea levels and accelerating coastal erosion. To ensure successful adaptation outcomes, island nations must be informed by big data and participatory geospatial tools to prioritize the preservation of existing ecosystems and the deployment of adaptive measures. These strategies offer a pathway for resource-constrained governments to implement sustainable and scalable adaptation strategies to protect their most vulnerable coastal communities.

Sergio Vallesi is a senior environmental engineer with over 20 years of multi-disciplinary international experience and has been consulting since 2018 for the World Bank Group, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, working on climate change-related assignments across various teams and regions, as well for universities, non-governmental organizations, and the private sector through his consultancy, Hydro Nexus.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.