This is how beach holidays could survive rising seas

Experts have laid out three ways to build resilience into the coastal tourism industry.

T

he COVID-19 pandemic will ensure summer 2020 is a washout for most. With international travel restrictions limiting holidays abroad, many people in the UK have opted to stay somewhere closer to home. As a result, there have been remarkable increases in the number of visitors to beaches across the UK. Thousands flocked to a beach in Bournemouth on a single day in June, causing the local council to declare a major incident.

But far greater disruptions to our summer holidays lie ahead. About half of all tourism takes place in coastal areas, but with global warming set to raise sea levels by somewhere around two metres over the next 80 years, how will our relationship with the coast change?

Will we commemorate the old coastal boundaries with forlorn sojourns above the sunken land? Will we recreate the beach in the heart of our cities? Or will we preserve the drowned coast as a nature reserve – a quiet memorial to what was lost?

We imagined three different versions of what a beach holiday might look like as climate change eclipses the coastline we once knew.

1. Floating in place

Sea level rise may seem a distant threat, but resorts and other tourism operators are already considering how they can stay near the coast and operate above the water. On the Caribbean island of Barbuda, resort huts have been built on stilts.

The aim is to keep tourism viable in the same place it has thrived for decades, while minimising damage from higher water levels.

Seasteading is one answer to this conundrum. The idea to build settlements on platforms at sea originated with the hope of creating more sustainable and equal societies away from land. The technology is still being developed, while researchers consider the engineering, legal and business implications.

New research suggests that coastal flooding could threaten up to 20% of global GDP by 2100, with much of it tied to the tourism industry. Tourism could instead become a new source of income for seasteads. Given the dwindling coastal space for tourists, creating new spaces out at sea might be a way to meet the problem of sea level rise head on.

Engineering could keep hotels afloat. Photo by jousi osorio on Unsplash

2. Bringing the beach to you

The urban beach is a concept that’s growing in popularity worldwide. It involves creating sandy areas in towns and cities by importing sand onto concrete. There may also be artificial pools and fairground rides. Each one has different features. There are family-friendly options, and those catered to adults, with cocktail bars or restaurants.

The opportunities for hedonism are still there, but instead of travelling miles to enjoy it, it’s right on your doorstep. Less travel means less carbon emissions, and urban beaches might help ease pressure on the real coast.

Perhaps the most famous urban beach is the Paris Plage. Since its opening in 2002, Parisians and summer tourists have been able to lounge under palm trees on the banks of the river Seine. It cost over two million Euros to create and has since been extended due to its popularity.

The Nottingham Riviera is an attempt to recreate this success in the UK. The landlocked beach in the middle of the city has sand and water, amusement arcades and beach bars.

The urban beach is becoming an industry in itself, with companies specialising in fake beaches that can be built as seasonal fixtures or permanent areas. If reaching the coast becomes too arduous in the future, these examples could provide everything needed for a seaside experience without the sea.

3. Rewilding the coast

Perhaps the most pragmatic solution is to accept nature taking its course and relinquish control as rising seas reshape the terrain. Allowing the new coastline to rewild could create millions of acres of new wetlands – habitats that are very good at storing carbon and that have deteriorated by about 50% since 1900.

Examples from Hong Kong, Spain, and Wallasea Island in the UK demonstrate how turning heavily managed coastal areas into new habitats can create new opportunities for wildlife and people.

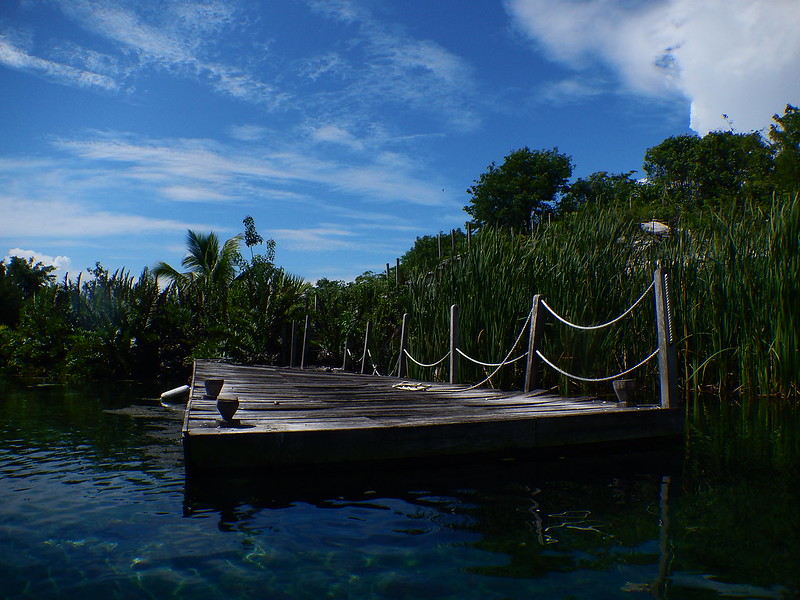

So does the Mexican island, Mayakoba. Its unique mangrove forests were damaged and polluted by the building of numerous hotel chains on the seafront, but today, only 10% of these hotels remain on the coast.

Rewilding the coast would provide new wetland habitat for threatened species. Lara Danielle/Flickr, CC BY

The local community abandoned their high-density model of tourism and protected the dunes and mangroves, which were being eroded by excessive development. New canal networks were dug to create an estuary, attracting birds and amphibians. This new wetland was designated as a nature reserve and visitors arrived to enjoy a new kind of tourist experience.

Visitor capacity and beach activities were reduced to ensure sensitive coastal environments could remain protected. But allowing the sea back into reclaimed coastal territory allowed a more sustainable model of tourism to flourish – one which could be replicated elsewhere as sea levels rise.

But before that can happen, our views of the coast must change. Humans once saw land and sea as a continuation of one another, rather than two discrete entities. Reviving this concept could allow us to navigate a future in which once certain borders have blurred beyond recognition.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.