Adapting to climate change could help us fight global inequality. Here’s how

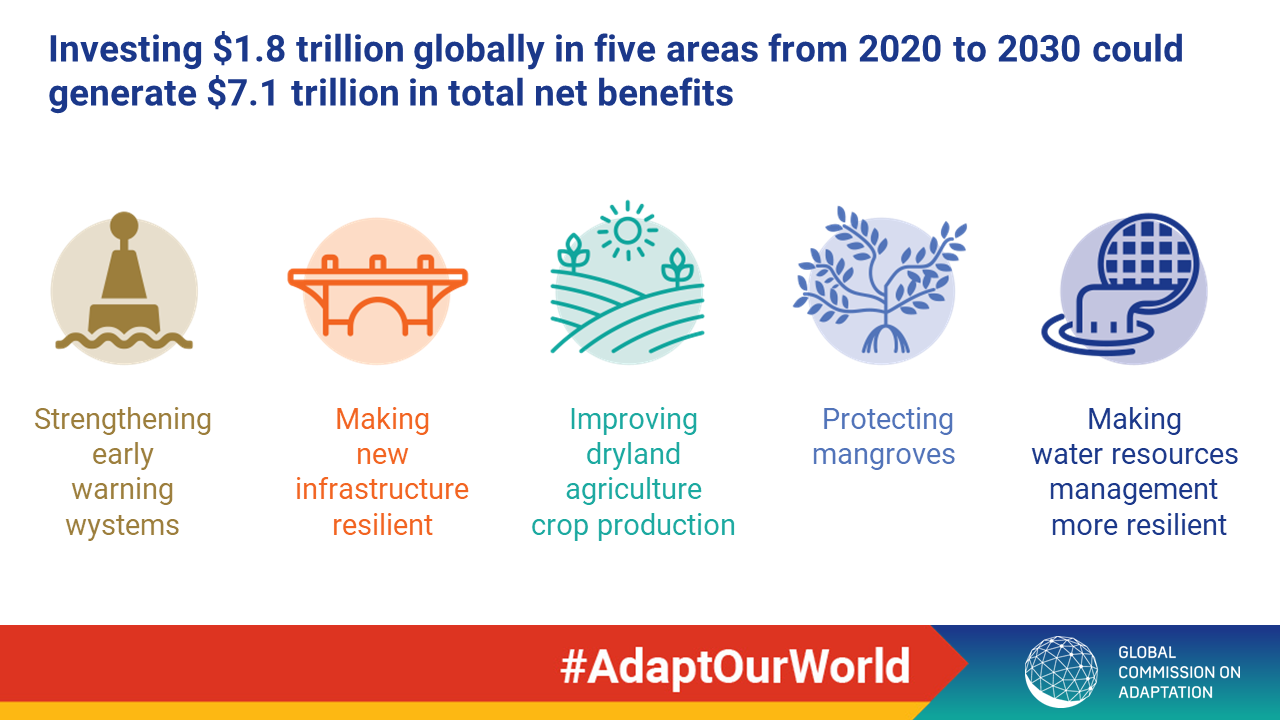

Investing $1.8 trillion in in projects to help communities adapt to the worsening impacts of climate change from 2020 to 2030 could generate $7.1 trillion in net benefits.

F

rom taxpayer-backed flood defences in Miami to shelters keeping Bangladeshis safe from storms, investing to protect against the growing effects of climate change pays, a global commission said on Tuesday, warning failure to do so will hike inequality.

As the planet heats up, governments and businesses must radically rethink how they make decisions in key economic areas such as agriculture and infrastructure, said a flagship report aimed at pushing adaptation measures up the political agenda.

“If we do not act now, climate change will super-charge the global gap between the haves and the have-nots,” said Ban Ki-moon, who co-chairs the Global Commission on Adaptation with billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates and World Bank CEO Kristalina Georgieva.

Former U.N. Secretary-General Ban said there were many opportunities to avoid losses caused by disasters and build economies that can better withstand wild weather like powerful Hurricane Dorian, which devastated the Bahamas this month.

But the commission – which is backed by 20 countries and 34 high-profile international figures – would need commitment from political leaders to expand the “bright spots” Ban had witnessed at the far larger scale needed, he said.

Investing $1.8 trillion globally in early warning systems, more robust infrastructure, improved crop production, mangrove protection and resilient water resources from 2020 to 2030 could generate $7.1 trillion in net benefits, the report said.

That amounts to an average of about $4 for every $1 spent, it said.

“In other words, failing to seize the economic benefits of climate adaptation with high-return investments would undermine trillions of dollars in potential growth and prosperity,” it added.

Without adaptation, climate change could cut agricultural yields by up to 30 percent by 2050, hitting the world’s 500 million small farms the hardest.

And it could force hundreds of millions of people in coastal cities from their homes, while pushing 100 million people into poverty in developing countries by 2030, the report warned.

Yet despite the cost of not acting and the potentially “huge” returns from doing so, climate risks were still not being factored adequately into decision-making, said Andrew Steer, a commissioner and head of the World Resources Institute.

Poor people, in particular, should be targeted with help to adapt to climate change, as they are often the most harshly affected by disasters but “do not have a voice”, said Steer.

Most funding for adaptation “never gets close to communities”, he added, urging a radical overhaul of how that money is provided so it reaches those who need it faster.

The report outlined actions that could enable key economic systems affected by climate change – from food production and water supplies to the natural environment and cities – to function better and provide for a growing global population.

Later this month, the commission will outline specific plans for a “year of action” on climate change adaptation.

Those will include working with finance ministers to build climate risks into spending and taxation, and a doubling of the scale of agricultural research to support farmers, it said.

Former U.N. climate chief Christiana Figueres said a common justification for not investing in adaptation was that it did not generate a direct revenue stream.

But instead, it should be viewed like good public health – as a way of keeping economies safe and allowing them to grow.

“The main message of this report is either we delay and pay, or we plan and prosper,” she told journalists ahead of its launch at a series of events around the world.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.