Can we feed our growing population without damaging the environment further?

A hotter planet means parts of the world once unsuitable for farming will soon be able to produce food. Should we take advantage of global warming and ramp up food production? The choice between feeding our growing population and risk accelerating climate change is a controversial one.

K

enya’s livestock herders planting chilli peppers, Pakistan’s mountain farmers rearing fish and tropical fruits in Sicily – farmers around the world are already shifting what they grow and breed to cope with rising temperatures and erratic weather.

In a few more decades, potatoes from the Russian tundra and corn from once-frigid areas of Canada could be added to the list as vast swathes of land previously unsuited to agriculture open up to farmers on a hotter planet.

Climate change could expand farmland globally by almost a third, a study by international researchers found this week.

They examined which new areas may become suitable for growing 12 key crops including rice, sugar, wheat, oil palm, cassava and soy.

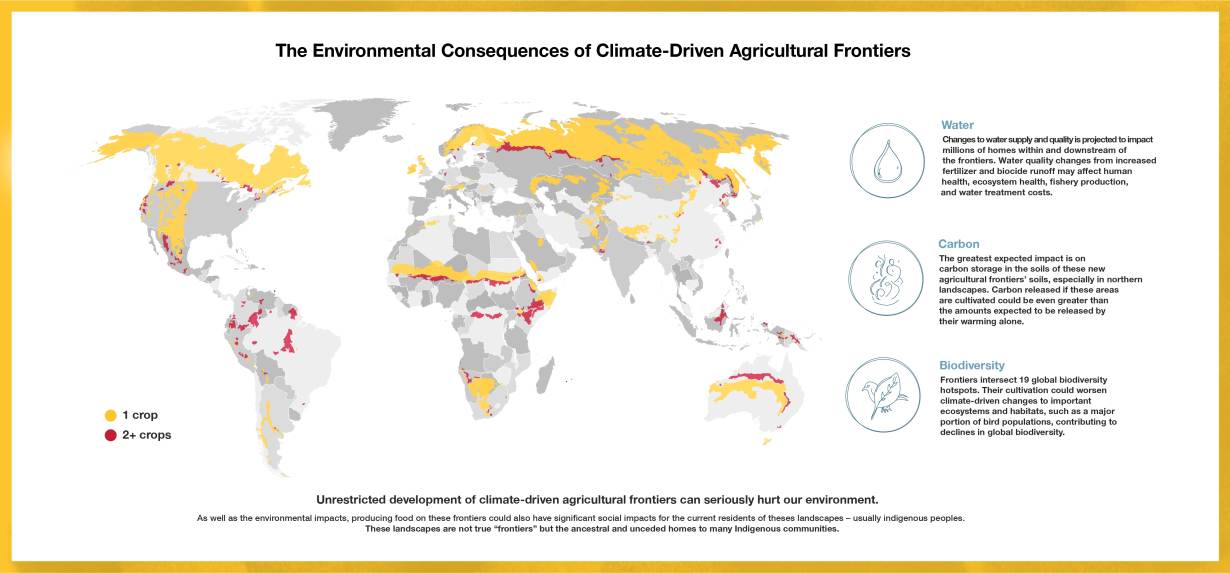

New areas of the world may be suitable farming regions thanks to rising global temperatures. Graphic by the Arrell Food Institute at the University of Guelph, Canada.

“In a warming world, Canada’s North may become our breadbasket of the future,” the scientists wrote.

But, they warned, opening up new “agricultural frontiers” would also bring significant environmental threats, including a risk of increased planet-warming emissions from soils.

In Canada, there is potential to at least double the country’s farmland to 2 million square kilometres, thus doubling food production, said study co-author Krishna Bahadur KC, an adjunct professor at Canada’s University of Guelph.

“This is the positive aspect,” he said.

Food security comes at a cost

Farming on the land identified in the study – more than half of which lies in Canada and Russia, with the rest including the mountains of Central Asia and North America’s Rocky Mountains – could help feed the planet’s growing population.

Today, one in nine people go to bed hungry, and the United Nations has said food production needs to increase by about 50% by 2050, when the global population is expected to reach nearly 10 billion.

Despite growing demand for food, environmental experts who were not involved in the study told the Thomson Reuters Foundation enlarging farmland could further accelerate climate change.

Some of these frontier areas have the most carbon-rich soils, said Ronald Vargas, secretary of the Global Soils Partnership and a land management officer at the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization.

“As soon as you start (farming) you will see emissions. So global warming will shoot up,” he said, pointing to a map showing that Russia and Canada hold about a third of the world’s organic carbon stock found in the top layer of fertile soil.

Within a decade, half of that carbon could be released into the atmosphere if the land is cultivated, he warned.

The study, published in the science journal PLOS One, echoed that concern.

If agriculture were allowed to extend into all areas identified, “there would be little chance” of meeting the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7F) above pre-industrial levels, it said.

That, in turn, would generate “even more climate change for poor people in the developing world” who have done little to cause global warming, said Margarita Astralaga, head of the environment and climate division at the International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Instead the answer lies with better management of existing arable land, including raising productivity in Africa, she said.

About four-fifths of African agriculture relies on rainfall, so extended droughts cripple food production, she noted, calling for solutions such as irrigation, soil conservation and reduction of food waste and spoilage.

“We have millions of hectares that already are arable that we have destroyed… Do we go to Mars next?” she asked.

Climbing temperatures has allowed mango farming in Sicily to increase.

A difficult balance

Agnes Kalibata, president of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa and former Rwandan agricultural minister, also saw downsides to opening up more farmland.

She pointed to the devastating locust invasion in East Africa and a surge in malaria in parts of Africa as the climate gets hotter.

“We can’t… forget that in those areas where it’s warming up, it’s also warming up to be comfortable for insects that were not there before,” she said.

Biodiversity loss could be “huge” too, added Kalibata, who was recently appointed special envoy for a U.N. summit on improving food systems slated for next year.

As well as threatening global biodiversity hotspots, the study warned that extending farming to frontier areas could bring risks for indigenous people who often inhabit such land.

It called for government policies to “optimise food production, biodiversity and ecosystem services under climate change” rather than simply favouring agricultural expansion, as in the past.

An environmentally aware approach could include protecting areas with carbon-rich soils or levying high carbon taxes on conversion of such land for farming, said co-author KC.

“We should proceed but we should move very, very cautiously and (be) mindful of the potential environmental impacts,” he added.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.