Kids in New York explore basements to find out how the city can adapt

I

n the fall of 2012, New York City received the brunt of an unprecedented storm. In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, also referred to as Superstorm Sandy, the stock market closed for two days. Some of the city’s subway tunnels, including six under the East River, flooded and were out of service for several days.

New York City public schools closed down. A week after the storm, 86 schools remained closed and 24 were so badly damaged that they were ultimately relocated.

Sandy left an impact and raised awareness that the city was indeed vulnerable to the effects of extreme weather and climate change.

In the aftermath, funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration allowed Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, the National Wildlife Federation, the Science and Resilience Institute at Jamaica Bay and New York Sea Grant to create the Resilient Schools Consortium (RiSC).

This in-school and after-school education program teaches students in Grades 6 to 12 about climate change, resiliency and vulnerability. More importantly, it is designed to centre youth voices and to support youth action for their schools, city and wider communities.

Authors Alexandra Gillis and Jennifer Adams served as evaluators, and Brett Branco as the principal investigator for the project.

Students investigate

RiSC uses online tools and interactive lessons to teach students about the changing climate and how to prepare for increased risks and hazards. In 2016, six schools participated in the program, three of which had been affected by Hurricane Sandy.

At one middle school in Brooklyn — the New York City borough just across the East River from Manhattan — the RiSC team did a routine classroom visit that highlights typical RiSC activity.

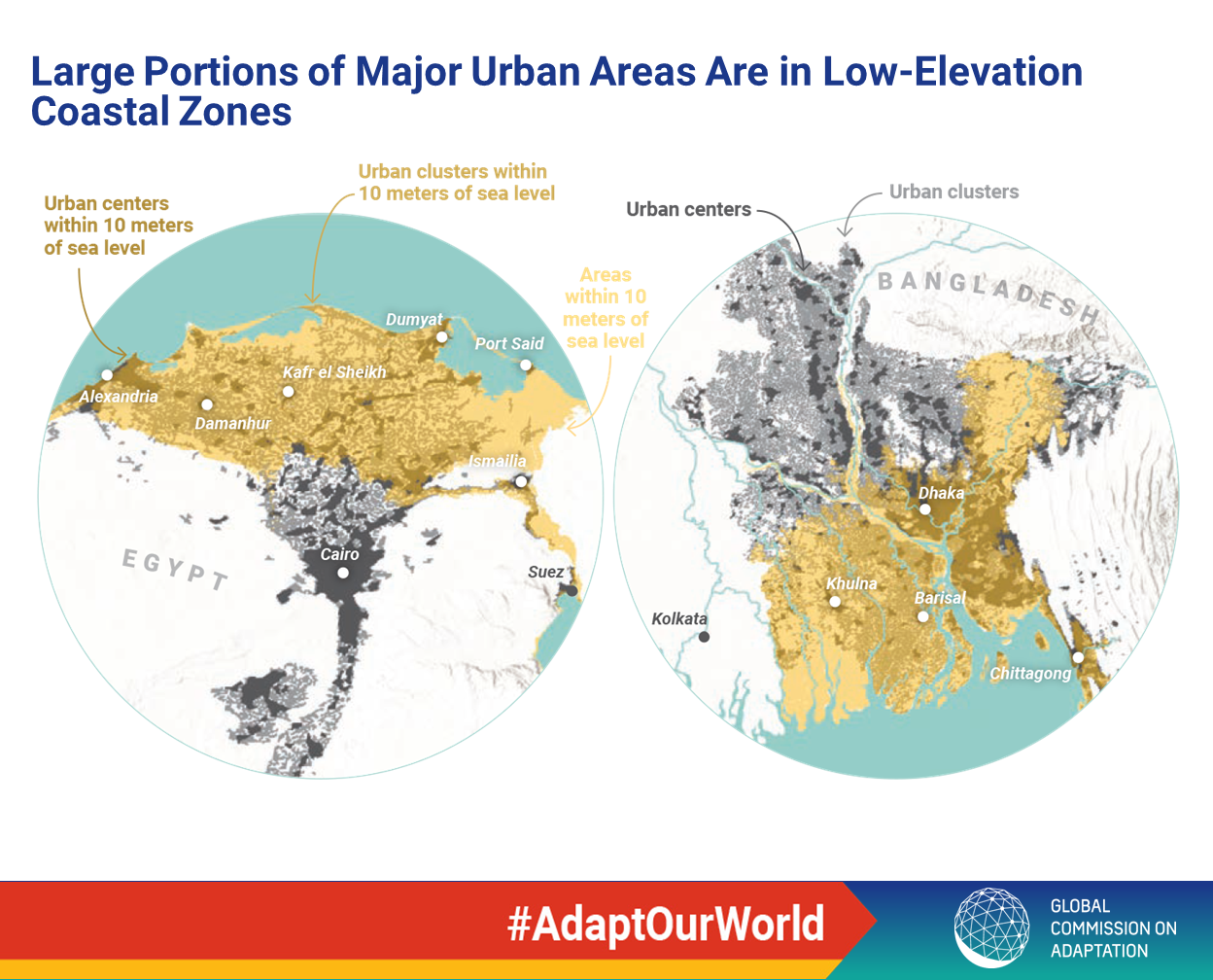

First, the students learned about how coastal cities are facing climate change. Then, as part of RiSC, students walked around the school building and grounds to assess the school infrastructure and report on damages and identify future weak spots or problem areas. Students were fascinated by visits to the boiler rooms and basements, seeing up close for the first time some of the lasting damage of the storm.

At this particular Brooklyn middle school, students reflected on their experiences. Lots of eager hands jumped up to share ideas for improving the school. One student shared the idea of expanding the maximum capacity of the school during a storm event. Since the students’ school is a designated shelter in a key high ground location in Brooklyn, the class conceptualized how to make sure as many people as possible can use the space.

Students went on to make connections between the integrity of the school’s roof, the water quality in the building, the location of the exits and the size of the auditorium — all of which contributed to the school being a viable shelter choice.

The class continued with a collective brainstorm on how to improve the safety of the school. They asked for information about how to make maps and who they should talk to about buying a water purification system.

One of the standout observations of this program is that students quickly agreed that there was a need for climate resiliency in their school buildings and responded: “What can we do right now?”

Image description

Reducing eco-anxiety

There has been a surge in the youth climate movement. Young people are making it clear that they don’t want anyone to pay lip service to climate change — they want action. Both common sense and research backs up why this generation seems to be at the end of their rope.

Factors that predict student interest in environmentally friendly practices (like picking up trash, recycling and finding a job that helps the environment) include a perception of self-confidence and a sense of oneness with a community.

Youth climate movements like these suggest young people understand they’ll be the ones who will have to manage impending climate disaster.

Youth know they’re not responsible for the political decisions that have harmed the planet, but must make their voices heard in order to have brighter futures.

The American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica released a report outlining the mental health impacts of climate change and guidance for scientific communicators. Their first recommendation was to “give people confidence that they can prepare for and mitigate climate change” — in other words, focus on action.

Schools, communities and people, especially those who are the most marginalized, need to feel empowered to respond and adapt to climate events and climate change.

Listening to students’ voices

When students are given the opportunity to present their ideas, talk to their community and design and implement resiliency projects, they feel like they are able to make changes. One student shared:

I told my friends and family that the RiSC program can make a great impact on the city’s actions and even the country.

At the end of the school year, RiSC students presented their findings, recommendations and projects to local climate and resilience professionals at a Youth Climate Summit in Brooklyn.

This was a positive experience for many students. One noted: ““I like to talk to professional(s) and share my ideas. I get to communicate and find ways and other ideas from others to solve these problems.”

These types of experiences allow students to feel part of a larger collective of problem-solvers.

The adults also benefited from hearing from the students. One Federal Emergency Management Agency official said the youth’s work is “just so encouraging and just gives me optimism and hope for the future.”

When youth are empowered to generate solutions to climate change, it allows them to imagine positive alternative futures.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.