Mangroves can be our secret weapon against climate change – let’s protect them

This often over-looked coastal ecosystem stores more than four times the carbon of a traditional rainforest and protects us from storms and floods – but they are under threat.

M

angroves – the semi-submerged trees and shrubs growing in saltwater in tropical climates – could prove a secret weapon in the war against climate change.

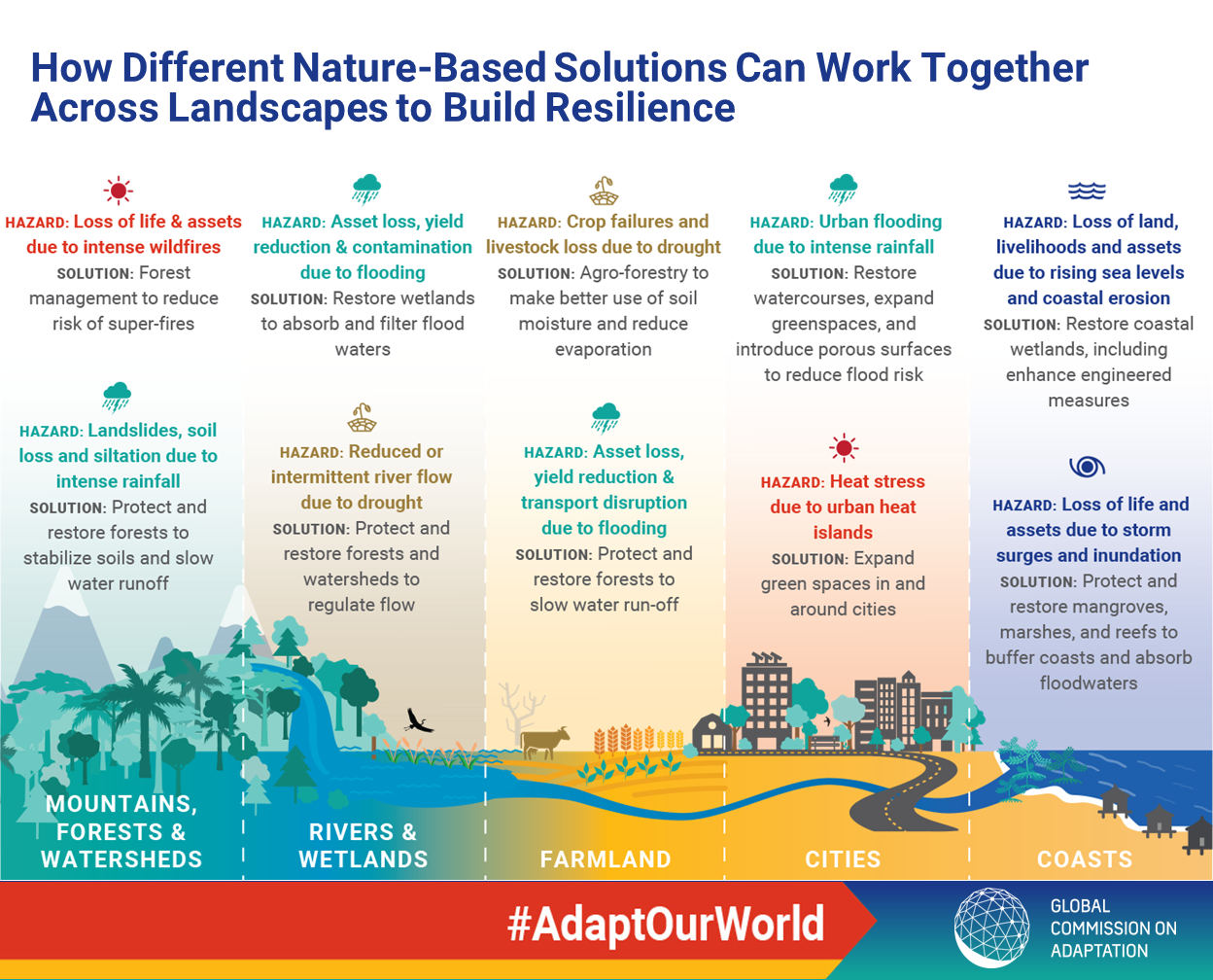

Able to absorb more than four times the carbon of a traditional rainforest on land, they increasingly figure in the toolkit of “nature-based solutions” being adopted by governments and organizations around the world.

Despite covering only 140,000 sq kilometers (54,000 sq miles) globally – less than 3% of the Amazon rainforest – mangroves store a disproportionate amount of CO2 in the dark, rich soil at the base of their exposed roots. One recent study estimated that such terrain captured 6.14bn metric tons of CO2 in 2000; around 50% higher than previously thought.

“They are often the stepchild of marine conservation – as they are muddy and buggy and hard to maneuver in,” says Gabby Ahmadia, lead marine scientist at the World Wildlife Fund. “And ownership gets confused or lost as they straddle the land and sea. But their benefits outweigh a few mosquito bites and dirty boots.”

Protecting these “blue forests” is even more pressing given the current high rate of mangrove loss. Developmental pressure on coastlines from agriculture, aquaculture and tourism caused the destruction of 35% of mangrove environments between 1980 and 2000; 75% of the soil carbon released came from just three countries – Indonesia, Malaysia and Myanmar.

Blue Forests – a Madagascar-focused initiative recently highlighted by the UK’s environmental minister Thérèse Coffey – is one of the many schemes worldwide looking to reverse this decline.

A recent Global Center on Adaptation (GCA) report highlighted action in Demak district on the north coast of Java, Indonesia, where locals have successfully restored over 20km (12.5 miles) of mangrove cover, helping to protect 70,000 people.

A UK-based start-up has proposed using drones to plant up to 100,000 trees a day in an area of 250 hectares (620 acres) of Myanmar’s Ayeyarwady Delta, where only 16% of original mangrove cover remains.

The umbrella organization Global Mangrove Alliance has said that it aims to increase global mangrove habit by 20% by 2030.

As well as their ability as carbon sinks, mangroves have a superb capacity to act as a shield from the effects of climate change. “They are five times more cost-effective than man-made infrastructure in protecting coastal communities from tsunamis and storm surges, as they reduce wave heights by up to 60% and reduce tsunami flood depth by 30%,” Coffey pointed out in her bulletin.

The GCA report estimates that mangroves prevent $80bn in losses per year from flooding and protect 18 million people.

The buffer effect mangroves provided was brought home by the devastation of the 2004 tsunami on Sri Lanka’s southern coastline, where around half such habitats have been lost and casualties were far higher in unprotected zones. After partially successful attempts at reforestation since then, the government announced in August a plan to add nearly 10,100 hectares (25,000 acres) to the 15,700 hectares (39,000 acres) of mangrove on state-owned land.

Mangroves, a unique marine ecosystem and source of biodiversity, are also a key economic resource for the people who live in them. The GCA report estimates that they provide $40-50bn annually in revenue from fishing, forestry and recreation.

Their long-term survival could depend on quantifying the benefits of such overlooked habitats, says Norman Duke, professorial research fellow at the James Cook University’s mangrove hub: “Our communities are driven by short-term gain in alternate land uses. There appears to be little regard for the advantages provided by natural ecosystems because they have rarely been valued in our terms. After all, their services have been provided for free. Why should we now pay for these benefits? This is the nut of the current dilemma.”

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.