These farmers in Bangladesh are floating their crops to adapt to climate change

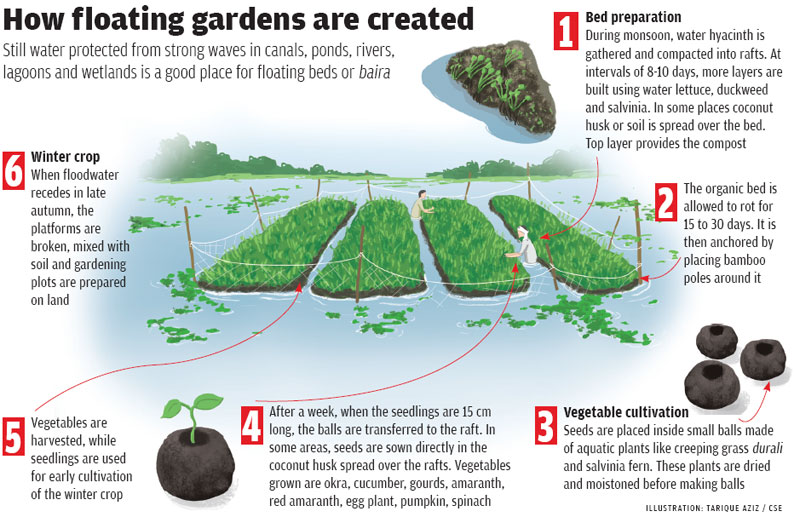

Bangladeshi farmers cope with monsoon flooding by growing crops on rafts made from water hyacinth – a traditional climate-adaptation technique that could help in many countries.

B

angladesh is one of the countries most vulnerable to the effects of climate change: situated on the world’s largest river delta, as much as 75% of its surface area is flooded during the monsoon season.

But farmers in the Bangladeshi lowlands have adapted to waterlogged conditions by sowing crops on floating rafts made of water-hyacinth plants. This traditional farming method is potentially transferrable to other areas of the world now facing similar issues with flooding because of climate change.

The rafts – up to 60m long and known as dhap – are built during the June to September monsoon season and allowed to decompose for a period, before balls of seedlings are sown in them. This allows farmers in Bangladeshi’s southern delta districts, such as Pirojpur, to continue growing vegetables in areas that are flooded for as much as eight months of the year.

Old ways, new funding

As the monsoon rains in Bangladesh become more intense and volatile, floating agriculture – practised in the country for around 300 years – has begun to attract attention as a means of both ensuring food security and farmers’ livelihoods in unpredictable conditions.

The Bangladeshi government invested $1.6m in 2013 in dhap pilot schemes involving 12,000 families in eight districts, as part of its climate adaptation strategy. NGOs such as IUCN, CARE and Practical Action are now also looking to the floating gardens to promote climate resiliency in areas around the country. The gardens offer an estimated 40% extra arable land for the cultivation of vegetables such as okra, cucumber, tomatoes, gourds and amaranth.

“This production system is the only food production and livelihood option for 60% to 90% of the country’s local communities, providing them with a diversified and nutritious diet thanks to the wide range of vegetables and spices it produces,” commends a recent report for the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, which has made dhap one of its 34 Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems. “Given the very specific and difficult growing conditions, production yields are satisfactory.”

As well as their role in stabilising food security when land is scarce, the floating rafts also point the way forward to more efficient forms of agriculture of the future that will be needed to feed the world’s growing population.

Experimentation

A form of hydroponics, in which plants draw up nutrients dissolved in water, they can be combined with fishing activities in the floodwaters underneath. The tightly intercropped, mostly organic floating farms are 10 times more productive than normal ones, and can be broken up to use as compost for land-based agriculture once the waters recede.

The principle is readily adaptable to other low-lying areas of the world. Indeed, comparable forms of agriculture have been practised under other names for centuries, such as the chinampas invented by the Aztec city-states in the valley of Mexico.

But the Bangladeshi version has its limitations. The floating rafts aren’t sturdy enough to withstand large waves and storm surges. Furthermore, with rising sea levels partly responsible for increased flooding, they are also threatened by rising salinity (water hyacinth does not tolerate salt). Dhap-builders have begun experimenting with using other materials to construct the rafts.

Traditional comeback

The holistic nature of traditional and indigenous agricultural methods – responding to, rather than trying to control, the natural world – could prove an important asset in climate-adaptation strategies.

Sequential cropping systems widely used in sub-Saharan Africa have been highlighted as one way of reacting to erratic weather patterns with careful crop selection.

Agroforestry – the planting of woody perennials into cultivated land, a practice that dates as far back as the Romans – is also increasingly incorporated as part of “climate-smart” agriculture, as a way of promoting biodiversity and preventing soil erosion.

In Australia, Aboriginal “fire-stick farming” has also attracted interest in sustainable-agriculture circles. The continent’s original inhabitants used their knowledge of local terrain and flora to make controlled burns in order to promote soil fertility and limit the effect of wildfires.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.