The fish helping crops grow in Duquesne could be a taste of the future

You may not have heard about ‘aquaponics’ – but in future it may supply the food on your plate. An innovative marriage of aquaculture and hydroponics, the concept is being tested in a Pennsylvania steelworks-turned-farm

S

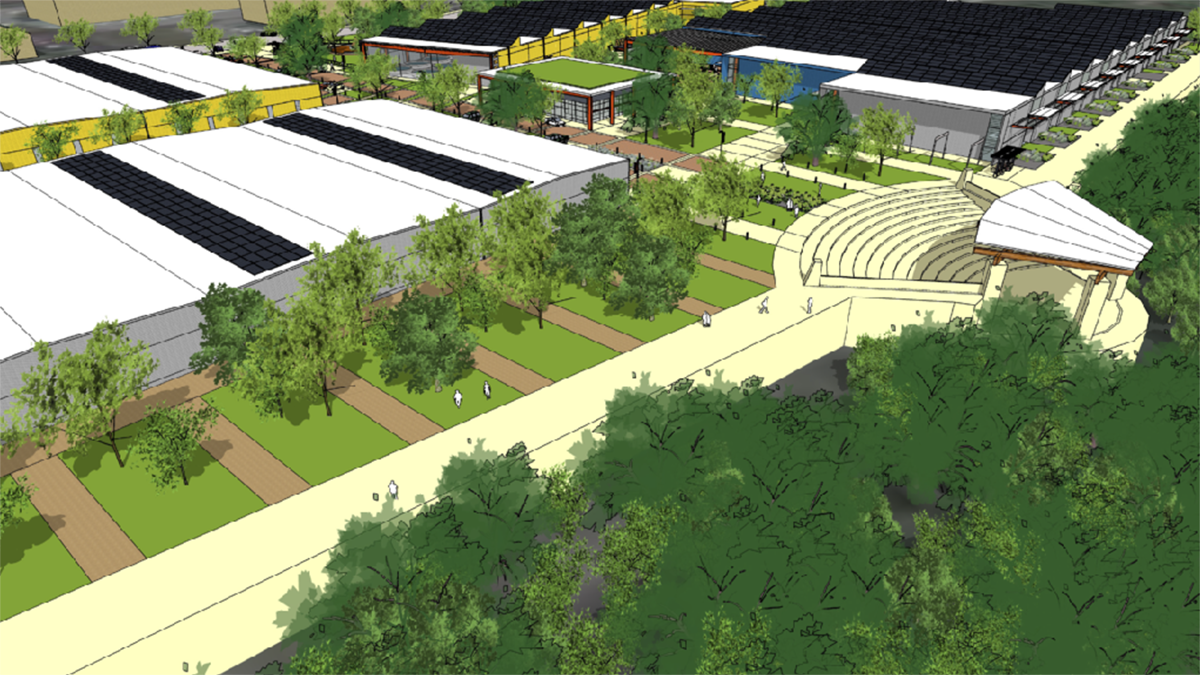

omething fishy is afoot in the city of Duquesne, a few miles southeast of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. If all goes to plan, a 25-acre riverside plot that was once home to a steelworks will become a farm fit for the future: one that will deliver jobs as well as sustainably grown food to the local area, all while helping to absorb the coming climate-driven shocks to food supplies.

This new facility, called InCity Farms, will tick all these boxes thanks to its use of aquaponics – a food production system that marries aquaculture and hydroponics (growing plants without soil) just as neatly as the portmanteau itself suggests.

Waste not want not

Like all living creatures, fish produce waste. In an aquaponics system, however, this isn’t seen as waste at all, but plant food. The waste water from tanks full of fish (trout and Arctic char, in InCity Farms’ case) is drawn away and passed through a filter, in which microbes convert ammonia in the waste into nitrates – a natural fertiliser. This nutrient-rich stream is then pumped directly over the roots of growing vegetables, which clean and filter the water as they draw food from it. The clean water is then returned to the fish tank. All being well, the fish are happy, the plants are happy – and so is the farmer, who can generate two income streams from a single closed-loop system.

Like the best ideas, aquaponics is deceptively simple – and when it comes to adapting our methods of food production in the face of climate change, it could help counter some of the greatest challenges heading our way.

Global fisheries, for example, are shrinking as a result of the warming oceans. In late 2019, the US Government closed the federal Alaskan cod fishery – and it is the changing climate, rather than overfishing, which has been blamed. Aquaponics systems can provide fish protein in a fully sustainable manner, and – especially in landlocked locations like Duquesne – negate the need to transport fish hundreds of miles inland.

Aquaponics farms are also an efficient way of reducing our reliance on resources that climate change is already depleting, such as the world’s store of fertile arable land. Global warming is one of the culprits behind the ongoing degradation of our soil; the UN estimates we may only have another 60 growing seasons left if soil continues to degrade at the current rate.

Supplies of the other main ingredient used in arable farming – water – are also under threat. Climate change is making droughts in food-growing areas like California longer and more severe. And on top of these challenges, the world will need to produce around 50% more food by 2050 to feed a global population that will, by then, have grown to 10 billion. If we are going to succeed, we will need to rethink and revolutionise the ways in which we produce food.

Aquaponics meets all these criteria. It doesn’t use any soil or artificial fertilisers, and because the system recycles its water, it uses far less than conventional farming methods – possibly as little as 10% versus soil-based agriculture. Proponents claim the yield-per-acre from an aquaponics system can be as much as four times that of traditional farms, too, which could help alleviate the pressures that climate change and our growing population are placing on the latter.

Source: InCity Farms

Salad days

Aquaponics might be new to Duquesne, but the sector is growing as fast as a lettuce fed on fish waste. One study this year estimated that the global aquaponics market, which was worth a little more than $500 million in 2017, will have quadrupled in size by 2026.

For Glenn Ford, the founder of InCity Farms, the proposed facility in Duquesne – and the jobs it will bring – fills a crucial social need in a town that has been through some hard times. “I decided to build our Aquaponics campus in Duquesne because it was a community in need,” he says. “Duquesne was a once powerful contributor to the Pennsylvania economy, and we believe we can assist it in improving its condition.”

But in the race to adapt food production systems around the world in the teeth of climate and demographic pressures, farms like the one planned for Duquesne could do more than nourish a community – they might just help to feed the world.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.