Adaptation finance takes off as Catastrophe Bonds top $100 billion

Catastrophe bonds have been around since the 1990s, but what exactly are they and how do they help our response to climate change?

T he total invested in catastrophe bonds since they were introduced in the 1990s has just passed USD 100 billion, according to figures from Aon Securities quoted in Reinsurance News. What exactly are catastrophe bonds, and what role can they play in climate change adaptation?

Catastrophe bonds, or cat bonds, are essentially a bet on whether or not a specified type of natural disaster will occur within a given timeframe – usually three to five years.

From the perspective of the investor in the cat bond, the bet pays off if the natural disaster doesn’t happen. They receive their investment back, plus interest. The interest rate has to be high to attract investors, because if the disaster does happen, they stand to lose some or all of their money.

Institutional investors

Cat bonds are typically issued by insurance companies, reinsurers – which insure insurers – or states. From the perspective of the issuer, the interest they offer to pay is like an insurance premium. If the envisaged disaster happens, they can access the invested money to mitigate their losses.

A growing number of large institutional investors, such as hedge funds and pension funds, see cat bonds as a way to diversify their investment portfolios: Aon Securities say the range of investors in cat bonds increased by 23 percent between 2015 and 2019.

Cat bonds are not all to do with climate change. They are one example of the broader category of insurance-linked securities, through which insurers can invite investors to take on a diverse range of risks, from earthquakes to terrorist events to rising longevity. But cat bonds are often used to cover risks of extreme weather events related to climate change.

Extreme weather risk

Investment bank Goldman Sachs, a leader in the development of cat bonds and insurance-linked securities, note in their environmental policy framework that “Effective management of catastrophic risk relating to weather extremes has become increasingly important for our clients.”

What kind of extreme weather risks do cat bonds cover? Artemis, a news source on the insurance industry, has a database of cat bonds and other insurance-linked securities going back to the 1990s. Recent examples mention risks ranging from windstorms in France to wildfires in California, and – in a bond sponsored by the Philippines government via the World Bank – tropical cyclones.

The USD 100 billion milestone is a sign that “the sector has shown strength in adversity”, says Aon Securities CEO Paul Schultz, after it “endured significant tests in recent times”. Financial Times columnist John Dizard explains those challenges: insurers experienced lower-than-expected losses from natural catastrophes in the ten years to 2017, leading to “complacency” – but then in 2018 the losses were “in excess of $71bn, the fourth worst on record”.

Source: Shutterstock

Resilience incentive

As climate change makes weather-related disasters more likely, logic dictates that cat bond issuers will need to offer higher interest rates to tempt investors. But cat bonds are not only a way to shift financial risks from one set of people to another. They can also offer an incentive to invest in making infrastructure more resilient to extreme weather events.

Cat bonds can be structured in different ways. Some are triggered by weather events themselves: say, if a hurricane of specified strength hits a defined geographical location. Others are triggered by the impacts of those events: say, if the financial losses from the hurricane exceed a certain level.

Cat bonds structured in the second way can create an incentive to invest in improving the resilience of infrastructure, much as the prospect of lower insurance premiums might incentivise a homeowner to invest in improving their home security.

Goldman Sachs say in their environmental policy framework that they are exploring “new models for catastrophe bonds that can better evaluate the benefits of increased investments. For example, enhanced physical resiliency, including flood barriers and stormwater detention structures, can improve the ability to withstand extreme weather events, which in turn could potentially be factored into the pricing and financial return models for catastrophe bonds.”

Innovation ongoing

As explained by Artemis editor-in-chief Steve Evans in a recent article, this refers in part to “hybrid financial risk transfer and investment structures that support resilient infrastructure projects, while also allowing for risk transfer, the much discussed resilience bond efforts”. The concept of resilience bonds has been around for some time: a 2017 BBC article gives the hypothetical example of a city seeking to issue a cat bond for flooding, investors agreeing to accept a lower interest rate if a stronger seawall is built, and the savings in interest enabling that investment in the seawall.

The idea has taken time to bring to fruition, with various possible models being discussed. Last September saw the launch of the Coalition for Climate Resilient Investment, a collaboration involving the Global Commission on Adaptation and partners from the public and private sector, which aims to bring together the necessary expertise to expedite progress.

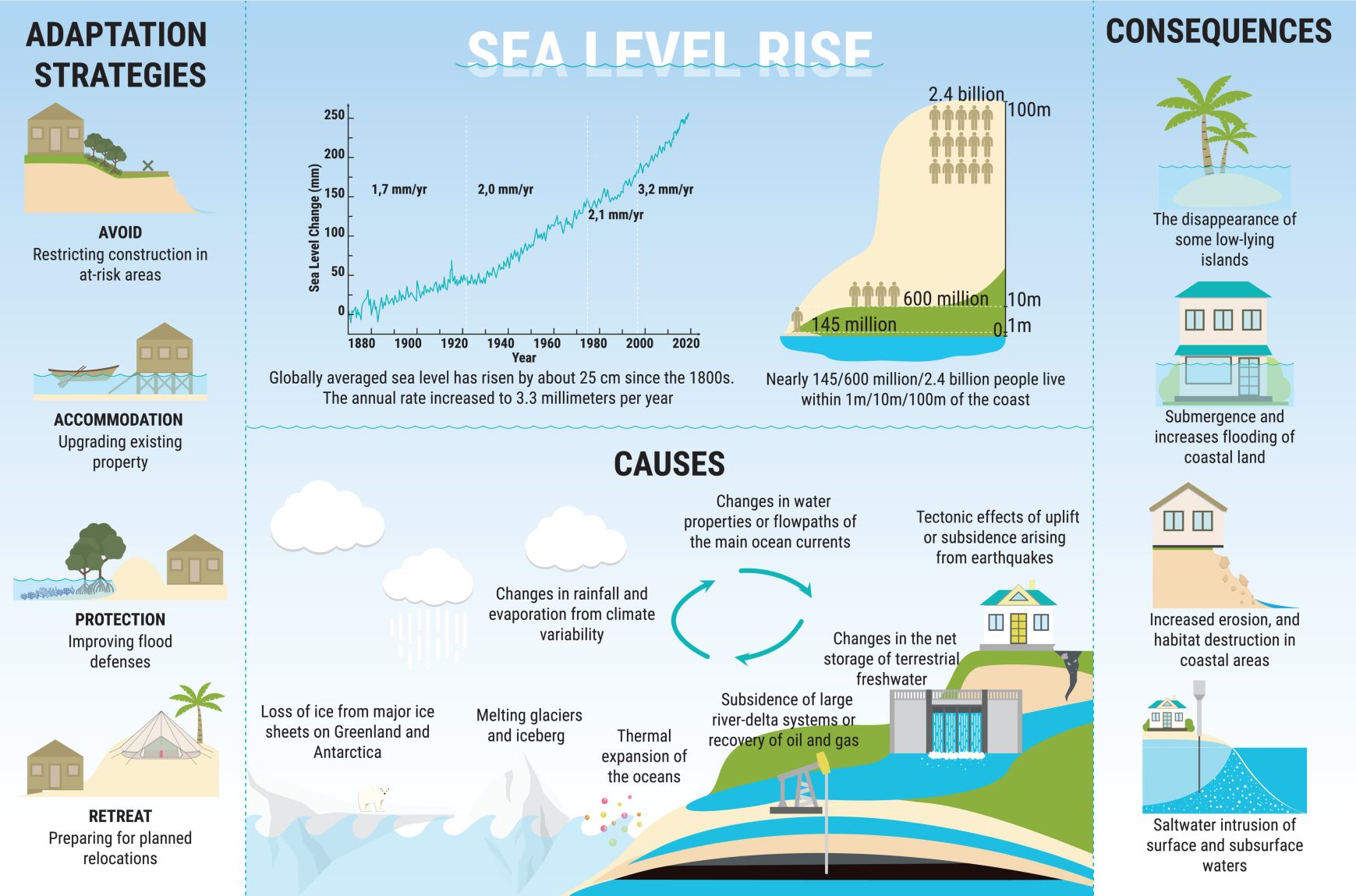

A great deal of innovation is currently happening in the use of financial instruments to leverage capital for climate change adaptation, as we have explored in recent articles such as those on blue bonds and instruments to finance measures against rising sea levels. The continued growth of the cat bonds market suggests they could play an increasingly significant role in the years to come.

The ideas presented in this article aim to inspire adaptation action – they are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Global Center on Adaptation.