What drives adaptation in rural households in Africa?

As the planet warms and the effects of climate change intensify, the risk of food insecurity in the world’s most vulnerable regions, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, has increased dramatically. Research by the Global Center on Adaptation (GCA) identifies two countries in this region that face high levels of food insecurity – Ethiopia and Niger – to show how accelerating adaptation to a changing climate in rural areas can help to fight hunger.

M

ore than a third of rural households in both countries have experienced drought or flooding in the past five years, and more than half of rural households in Niger and 20 percent in Ethiopia are food insecure. However, adaptation strategies in both countries are not yet widespread.

GCA research shows that only a third of households in Niger and half of households in Ethiopia have adopted climate smart agricultural practices on their farms – an adaptive production strategy. Further, about half of households in Ethiopia and Niger diversify their income sources to non- or off-farm activities. But to avoid food insecurity resulting from climate change and other stressors, adaptation by small-scale, subsistence farms must be accelerated.

How Gender, Education and Risk Perception impact Adaptation

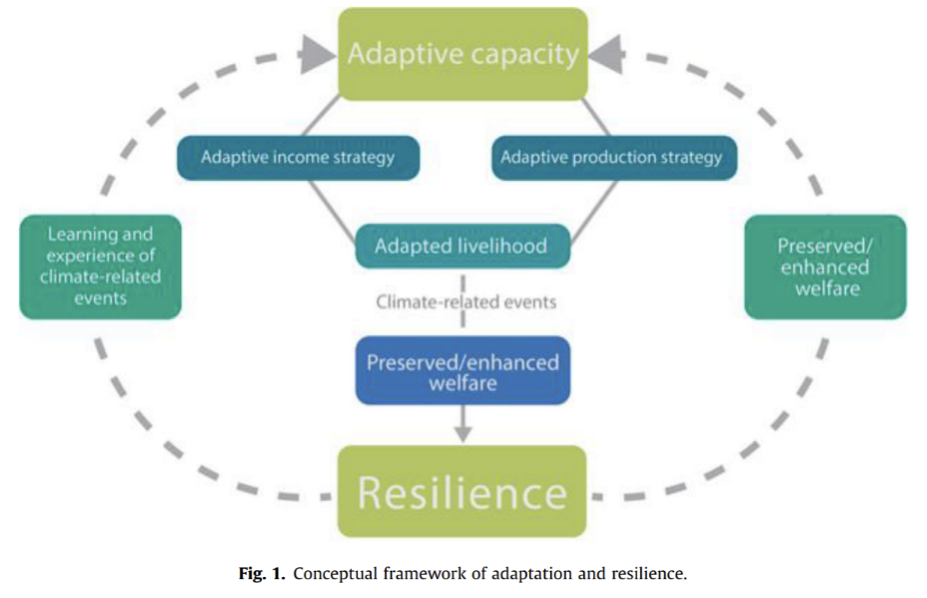

Adaptive capacity empowers people to anticipate and respond to change, minimize its consequences, recover and take advantage of new opportunities based on their willingness and ability to convert resources into effective adaptive action.

In terms of climate change, a resilient household is able to preserve and enhance welfare over time and in the face of climate events.

In a scientific article published in March, GCA’s Research for Impact team shared a series of findings about what drives adaptation in Ethiopia and Niger.

Adaptation is associated with increased welfare in the form of food security but only to a limited extent. Not surprisingly, formal education plays an important role in adaptation and the perception of food security. This is important as it suggests that investments in education could result in a double-barrelled pay-off, both in terms of welfare and adaptation.

Female-headed households appear to feel more food insecure and asset holdings are important to perceived food security. In both countries, female-headed households are less likely to have engaged in on-farm adaptation.

Results for exposure to climate impacts are mixed. In contrast to Niger, female-headed households in Ethiopia have more diversified sources of income and are therefore less exposed compared to their male counterparts.

Asset ownership is an important driver of adaptation and past experience of climate hazards is strongly associated with adaptation. This confirms that adaptation can take place autonomously although risk perception strongly varies between people. For example, the underrepresentation of women in many spheres is said to influence risk prioritization and the purchase of insurance. In West Africa, it has been shown that men tend to weigh risks to their farm activities more heavily while women are more concerned about shocks affecting the health and schooling of household members. This points to a sharp difference in the kinds of shocks that men and women are likely to insure against, and their willingness to pay for a given coping instrument. This could explain why female headed households are much less likely to adapt.

The Unequal Geographical Distribution of Climate Risk

GCA’s researchers found that the risk of climate change impact is unequally distributed at a subnational level. One department in Niger and four zones in Ethiopia can be considered critically in need of adaptation. These micro-regions have high food insecurity, are highly exposed and vulnerable to climate events.

Niger’s most affected department, Thcin Tabaradene, is in the north of the Tahoua region, which is partly in the Sahelian zone and extremely arid. It houses large numbers of transhuman and nomadic pastoralists and the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) has identified that it experiences food security stress. In Ethiopia, all three critical zones, Nuer, Borena, and Liben, are in the lowlands and have a high share of pastoralists. Nuer is prone to flooding and Borena and Liben are at risk of drought. According to FEWS NET, in 2015 both Borena and Liben were stressed in terms of food insecurity.

Both countries also contain a high number of medium-risk regions with high exposure to climate events. In contrast to Ethiopia, Niger also counts a high number of medium-priority areas with high vulnerability. The low priority micro-region of Arlit contains uranium mines, which means that incomes are likely to be more diversified. The Niger river flows through the departments of Say and Gaya, allowing for flood recession agriculture and gardening. The departments of Birni N’Konni and Madarounfa border the seasonal Maggia River and households are engaged in irrigated cash cropping of onions, primarily, for urban areas of Nigeria.

Three Lessons to Accelerate Adaptation:

- Adaptive behaviour can be enhanced through cash transfers that allow households to build up their asset base. Investments in education can be a pathway towards resilience. In addition to formal education, the current state of households could be shifted by research-based adaptation learning support, which can accelerate behavioral and policy change by maximizing learning before and during adaptive decision-making.

- There is an important gender dimension to adaptation. In both countries, female-headed households are more vulnerable because they have not engaged in adaptative production strategies. In Niger, female-headed households are also more food insecure. The adaptive capacity of female-headed households, particularly on-farm adaptation, must be improved.

- Critical areas in Ethiopia and Niger are representative of the spatial poverty traps that exist and need to be prioritized to accelerate adaptation. Classifying risk at the level of micro-regions aids adaptation planning. When looking to accelerate adaptation, policy makers should make sure to prioritize these critical and high-priority areas.

One of the core pillars of GCA’s flagship Africa Adaptation Acceleration Program (AAAP), implemented jointly with the African Development Bank, focuses on Climate Smart Digital Agricultural Technologies (CSDAT). Smallholder farmers record a 40 – 70% increase in yield and income when digital solutions are used and this initiative aims to harness the power of digital technology and innovation to improve agricultural productivity in the African continent. The CSDAT pillar aims to scale up access to climate smart digital adaptation solutions, and data-driven agricultural and financial services, for at least 30 million farmers in Africa, to support resilient food systems in 26 African countries and reduce malnutrition for at least 10 million people by 2050.

The Smallholder Adaptation Accelerator is the implementation vehicle of the CSDAT pillar and outlines knowledge and analytical needs to influence decision-making and ensure the sustained uptake of Climate Smart Agriculture strategies at scale.

Dr. Fleur Wouterse is GCA’s Director of Research, leading the Research for Impact Team. As a development economist, she has studied the economic behavior of smallholder farmers in Africa. She has a PhD in Development Economics from Wageningen University in the Netherlands and more than 20 years of experience in academia and international research organizations, particularly in Ethiopia, Senegal and Uganda.